In Ancient Rome, if you were running for office, you would don a bright, white toga. The Latin word referring to those togas, candidus – “pure white, glistening” – gave us our modern word candidate.

In modern times, our candidates announce their runs with slogans. A good slogan can move a nation – much like Barack Obama’s 2008 slogan, “Yes, we can”, or Labor’s 1972 slogan, “It’s time”.

Australia’s 2025 election has given us F-grade slogans – “fine”, “functional” and “forgettable”.

Fifty years ago today, Gough Whitlam became Prime Minister of Australia - a true visionary.

There is almost no one in our country who's life hasn't been touched by Gough's legacy.

From providing universal access to health and education. pic.twitter.com/wt8TUOYPSt— Chris Minns (@ChrisMinnsMP) December 2, 2022

But any slogan – even the forgettable ones – carry echoes of what makes a slogan good. Let’s look at good slogan-making – but also why these “triple F” slogans might be a good strategy in 2025.

Old English rhymes for the time

Australia’s 2025 election slogans hit some basic linguistic notes:

- Australian Labor Party (ALP): “Building Australia’s future”

- Liberal Party: “Let’s get Australia back on track”

A good slogan tends to use Old English words. These are words with the longest heritage in the English language. Old English words are short, impactful, and accessible to those who haven’t attended university.

In contrast, words derived from French, Latin and Greek tend to be opaque and sound like business jargon. Two of Australia’s all-time worst slogans were the Latin/French-full “Reconciliation, Recovery and Reconstruction” (ALP, 1983), and “Incentivation” (Liberal, 1987).

Back to 2025, all words in this year’s slogans are Old English except for two – “Australia” and “get”. I suppose we can give the parties a bye on Latin-derived “Australia”. We might also give the Liberal Party a bye on Viking-borrowed “get”. The word “get” sounds Old English in that it is short and contains the “tough” sounds “g” and “t”.

Sounds like “p/b”, “t/d” and “k/g” tend to convey strength, assertiveness and decisiveness. It’s no wonder these sounds are over-represented in swear words, but also in slogans such as “axe the tax”, “stop the boats”, and “technology not taxes”.

We also see these sounds in the Liberal Party’s “back on track”, which hints at three other key slogan strategies – metaphor, rhyme, and the rhetorical three.

The magic of metaphor, rhyme, and rhetoric

Tech ethicist Tristan Harris has pointed out that magicians (and tech bros) don’t need to know your strengths for magic to work – they only need to know your weaknesses. To these ends, the poetic nature of language can leave us spellbound in ways we’re not always aware of.

Since the time of Aristotle, it’s been noted that metaphors can invoke new worlds, and influence the way we think about our current world. This year’s slogans both have a metaphorical quality (“back on track”, “building Australia’s future”). “Track” has had a neutral, metaphorical sense since the 17th century. We’ve been speaking about being “on the right track” since the 19th century. We’ve been figuratively “building” since the 15th century.

Both slogans also hint at the rhetorical rule of “three”, or the “tricolon”. This is the use of three parallel words, phrases or utterances.

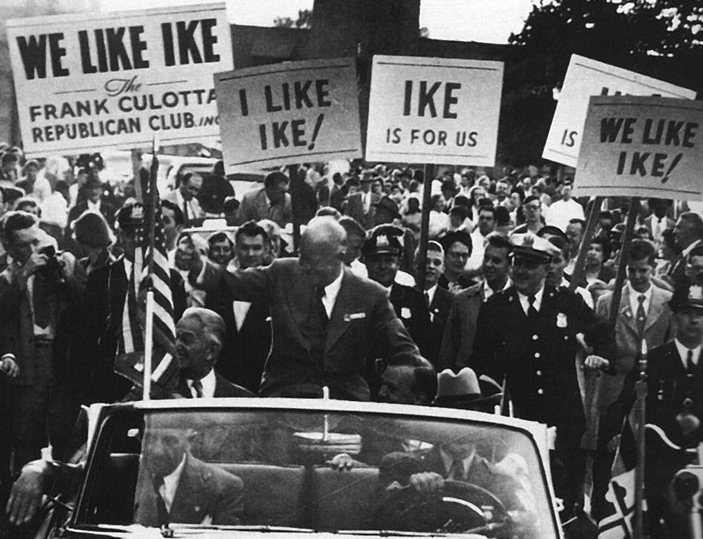

The ALP does this with “Building Australia’s future” and the Liberal Party through its “back on track”. This rhetorical strategy dates to Ancient Greece, but its use in political sloganeering is most famously associated with former US president Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower.

Ike’s 1952 presidential campaign was the first to adopt “many of the techniques of commercial advertising and applying pithy Madison Avenue language to the electoral context” (in the words of GOP political messaging guru, Frank Luntz).

Eisenhower’s media advisor was Rosser Reeves, the advertising legend responsible for M&Ms’ “Melts in your mouth, not in your hand”. Reeves realised that Ike wasn’t a terribly engaging speaker, but that political audiences didn’t have great memories anyways.

Rosser, with famed pollster George Gallup, developed the “Eisenhower answers America” advertising spots. In a 37-second TV spot, a voter would ask Ike a question, and he would give a pithy answer. It was the birth of the political soundbite and prominence of the three-word slogan (the campaign also gifted us “I like Ike”).

We see echoes of another strategy from 1952 in this year’s Liberal slogan – rhyme (“back on track”). Research shows that rhymes and alliteration are generally more memorable and more likely to be judged as true.

Plagiarism, echoes of efficiency, or deliberate choice?

So, this year’s ALP and Liberal Party slogans aren’t bad in the strictest linguistic sense – they’re “fine” and “functional”. And yet, these slogans are also “forgettable”.

This year’s slogans seem to be drawn from a pool of often reused (or plagiarised) slogans. This year’s Liberal Party slogan echoes that of the 2023 New Zealand conservatives’ slogan, “Get our country back on track”. And, as for the ALP’s slogan, the Liberals were “Protecting, securing, building Australia’s future” in 2004.

In sloganeering, plagiarism is hardly unique. US President Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” was used as a presidential slogan by President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s (and used earlier in 1964, by candidate Barry Goldwater).

One cynical explanation for the forgettability of slogans is that there is room for improvement. For instance, you still sometimes see political words being used where their use has been derided by some political pundits.

In their election speeches, both Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Opposition Leader Peter Dutton tout their “plans”. US political pundits such as Frank Luntz have poured cold water on “plan” as a political word – it doesn’t sound “sufficiently binding, plus we all know what happens to the best-laid plans”.

A few months ago, Dutton promoted his “compact with Australia” (as have other Australian politicians before him). This echoes the famed American “Contract with America”, the slogan that contributed to US Republicans’ shock 1994 win of Congress. But the underlying power of the “contract” was its specificity and accountability – US politicians promised they wouldn’t run for re-elections if they didn’t fulfil the “contract”.

But, of course, these campaigns are run by astute political agents facing increasingly diverse voting publics in increasingly diverse seats. One less cynical interpretation is that it’s hard to target such diverse voting publics with a “one-size-fits-all” slogan.

Nevertheless, whatever the slogan or purpose, US journalist Edward Morrow long ago cautioned that we should not “mistake slogans for solutions”.