I’ve been an editor and author of children’s and young adult books for over 20 years. I’ve taught writing for children and young adult fiction to hardworking and serious emerging writers since 2010.

So yes, it yanks my chain when I read that Keira Knightley has written and illustrated a “modern classic” – a children’s picture book called I Love You Just the Same, scheduled for publication next year. And of course, that Jamie Oliver has pulled his children’s book, apologising (along with his publisher, Penguin Random House UK), for falling short when it comes to Indigenous representation. They join the likes of Madonna, Meghan Markle, Jimmy Barnes, Keith Richards and more.

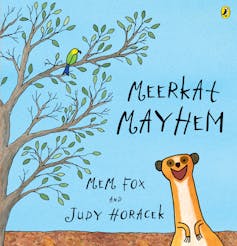

Children’s authors and illustrators occupy a highly specialised niche of publishing. Picture book writer Mem Fox, who has written 49 picture books for children, took three years to write her most recent book, Meerkat Mayhem, illustrated by Judy Horacek.

Picture books are written to be read aloud, and every word needs to be carefully chosen for meaning, rhythm, readability and musicality.

My middle-grade novel, The Endsister, was written for the same age group as Jamie Oliver’s book. It tells the story of a family who inherit a house and move to London. It took several drafts to find the right balance between the child protagonists and the adult characters.

In children’s literature, kids need to make mistakes and solve their own problems. Moving to London is adult business, but how the young characters in my book respond and what they do next is the beating heart of the story.

Being a children’s writer, and learning how to make these kinds of storytelling decisions (in a way that should feel easy to readers), is a careful craft.

Tired tropes and nothing new

The problem with most celebrity children’s books is not that they are bad, but that they are derivative. They don’t contribute anything new. They reproduce old ideas about what stories for children should be like, usually reflecting tired tropes from the books they read when they were kids.

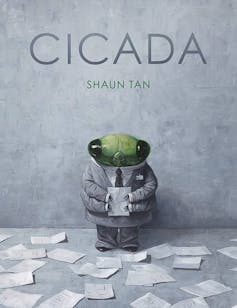

Celebrity writers who are signed for their name-brand sales appeal aren’t gently pushing aesthetic boundaries, like the picture books of Margaret Wild, Shaun Tan or Heidi McKinnon.

They don’t draw their readers into immersive visual worlds, like Lisa Kennedy, Bob Graham, Remy Lai, or Jeannie Baker. They don’t look into the hearts of ordinary contemporary kids with empathy and wisdom, like Nova Weetman or Rebecca Lim.

I have gone to countless high schools and primary schools to talk about writing. Many children didn’t know they had read one of my books until I showed them the covers. That’s because most kids don’t really care who wrote the book; what sticks is a character’s odd name, an image, or a general vibe. (Just look at reddit’s r/whatsthatbook thread.)

Why, then, do publishers love a celebrity children’s author? The entire publishing industry is based on hunches – calculated ones, but still essentially hunches. At least a celebrity name is a measurable data point – if not for the children, then for the algorithm, and the parents and grandparents buying the books.

Who actually writes celebrity children’s books?

According to Jamie Oliver, his middle-grade adventure series began as bedtime stories he told to his kids. In order to keep track of the narrative, he recorded himself. One imagines (but can’t know) that these recordings have been transcribed and edited or rewritten.

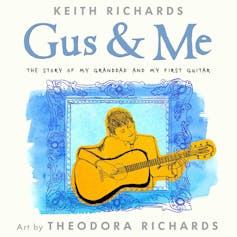

Very rarely, a coauthor will be listed. Bill Shapiro, a journalist and former editor of LIFE magazine, helped author Keith Richards’ biographical picture book, Gus and Me, though weirdly, Bill Shapiro isn't a children’s author either.

If celebrity children’s books are being marketed on their names, then shouldn’t publishers be more transparent about who is writing and editing these books? This seems especially important in light of generative AI, where trust can be easily eroded.

Australian comedians and children’s publishing

It’s worth pointing out that most celebrity children’s authors in Australia are comedians. They’ve been writing for their whole careers. They know how to engage an audience or create a compelling character.

A picture book, as my colleague Denise Chapman, a poet and children’s literature expert, said to me, is both page and stage. Children’s books are often also a performance, an event, a reading experience.

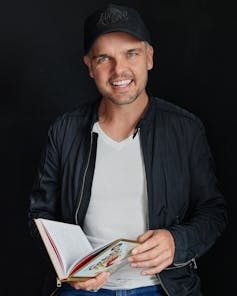

There can be a blurry line between celebrity author and multi-talented artist. Tristan Bancks, for example, is a collegial and hardworking author who some of us might remember as Tug from Home and Away. He makes energetic book trailers, while also channelling Tug’s brooding energy into books such as the award-winning Scar Town.

Pig the Pug and The Bad Guys author Aaron Blabey was an actor, too – he was the titular character in one of my favourite television shows ever, The Damnation of Harvey McHugh.

Who pays?

When you publish a book in Australia, you fill out an author questionnaire for your publisher. It asks for a list of your contacts and networks. Who will write an endorsement? Who will feature your book in the media? Many debut authors feel they’ve failed before they’ve even begun, as they leave these sections blank.

The marketing budget of a book is a percentage of the expected revenue. Higher advances are based on projected sales. While celebrities might bring higher sales because of their cultural capital, publishers still redirect resources to support these celebrities and promote their books.

The average advance in children’s books is A$4300, with many picture-book authors receiving a lot less.

If your picturebook advance is $1000, publicity and marketing might be limited to listing your book in the publisher’s catalogue and sending out a few review copies. The authors who need the most support when it comes to marketing are probably going to get the least.

Every celebrity children’s book under the Christmas tree is a missed opportunity to connect readers with writers. And I think this doesn’t just sell children’s writers and illustrators short. It undervalues children as readers as well.

Penni Russon’s books have been published by Allen & Unwin and Penguin Random House, both of whom are mentioned in this article. She currently supervise Rebecca Lim's PhD at Monash University.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.