The use of artificial intelligence (AI) to create non-consensual sexualised deepfake images is rising in popularity among high school students, and is the latest emerging form of image-based sexual abuse.

Image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) involves the creation, sharing, or threat to create or share sexual images of another person without their consent. Sexualised deepfake abuse involves the use of AI “deep learning” software to produce “fake” sexually-explicit images of an individual that often appear authentic, without their consent.

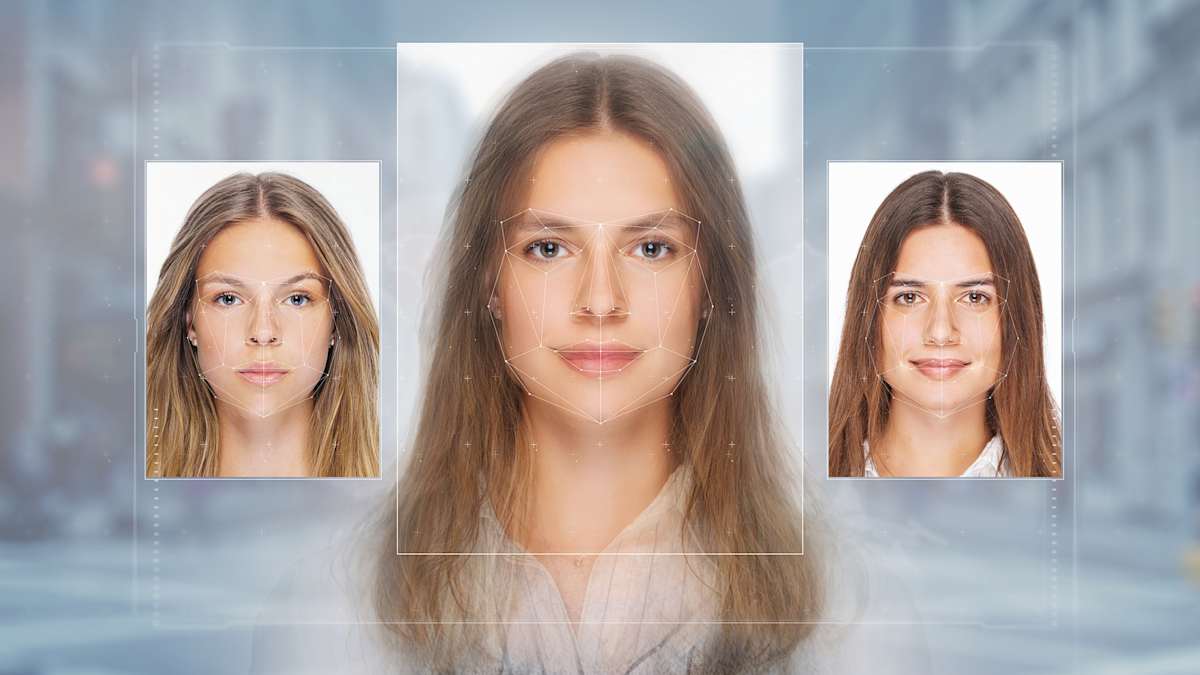

Sexualised deepfakes come in various forms. They may be created by superimposing an individual’s face onto existing pornography.

This form of sexualised deepfake abuse violates the consent and sexual autonomy of both the person whose face has been superimposed onto existing pornography, and the adult performer whose content is being used in a way they did not authorise.

A sexual image may also be generated based solely on non-sexual images of a person. For instance, nudify apps can be used to undress someone by uploading their image and choosing an “ideal” body type.

There are also multiple sites across the internet where non-consensual sexualised deepfake content can be consumed as “pornography”. Many of these sites are advertised to young people via social media platforms such as Reddit, Facebook, and Instagram.

Research has found that young people are creating non-consensual sexualised deepfakes at higher rates than other age groups. This isn’t entirely surprising, as young people are often the first to take up new technologies.

There have been multiple recent incidents reported of young students creating sexualised deepfakes of their peers and teachers, which are uploaded to social media where they may be viewed and shared by others. This is occurring within a context of rising rates of misogyny in high schools.

Read more: Gendered violence in schools: Urgent need for prevention and intervention amid rising hostilities

In response, the Australian government wants to introduce new laws that criminalise the creation and sharing of non-consensual sexualised deepfakes.

However, sexualised deepfakes of children fall under federal child sexual abuse material laws. The government is also implementing various measures to prevent young people’s misuse of technology through social media bans and pornography age verification laws.

Read more: Proposal to ban access to social media reflects a lack of understanding

While criminalisation highlights the seriousness of this form of abuse, many of these measures are arguably informed by moral panic, adult paternalism, and policies that don’t address the root cause of sexualised deepfake abuse.

A social media ban won’t keep my teenagers safe – it just takes away the place they love | Anna Spargo-Ryan https://t.co/qgIjI3NRe9— The Guardian (@guardian) May 26, 2024

The stringent measures also unfairly punish young people for their use of technologies, which have been created by adults who are actively benefiting from young people’s engagement with the digital world.

Significantly, these measures also place the onus onto young people (and their parents/guardians), where the responsibility should lie with the creators of deepfake technology.

While there’s an emerging body of research on sexualised deepfake abuse, there’s limited research to date exploring the importance of shifting social and cultural attitudes that lead to this form of IBSA.

Sexualised deepfake abuse is often framed as a novel, emerging crisis characterised by the looming threat of developing technology. However, deepfake technologies are merely tools; they’re not in and of themselves responsible for the creation of sexualised deepfake abuse.

Sexualised deepfake abuse can partially arise from support for misogynistic attitudes, such as viewing women as sexual objects, and men’s feelings of entitlement to sex and women’s bodies.

These attitudes are reflective of the masculine and heterosexual dominance that continues to persist in Western society.

The idea that banning young people from social media will prevent issues such as sexualised deepfake abuse relies on the logic that misogyny is limited to online spaces, when in reality it permeates all aspects of society.

It also fails to acknowledge the interconnectedness of online and offline worlds, as young people now socialise predominantly via digital technologies.

Young people, particularly marginalised groups, gain many benefits from their use of social media. To lump all sexual content together into a monolithic, negative category is to deny young people access to positive, constructive and egalitarian narratives of sexual expression.

Barring young people from using new technologies also denies them of their agency and ability to engage with technology ethically.

Education is a factor

Education that combines digital literacy with comprehensive sex education is one way to tackle this rising form of abuse that is informed by longstanding attitudes.

My research will involve engaging directly with young people to understand their attitudes and perspectives on deepfake creation and consumption.

Asking young people how they are thinking about sexualised deepfakes as a form of IBSA can provide insight into what kind of educational materials and resources might be useful to redress the harms of sexualised deepfake abuse. Prevention is also more likely to be effective when young people are being listened to and their needs addressed.

Research shows that young people are thinking critically about their use of AI and about the ethical implications of their use of deepfake technology. Incorporating young people’s perspectives into research allows for a more balanced approach to prevention that considers their voices.

Young people aren’t passive victims of technology. They play an active role in shaping how deepfake technology is thought about and used.

Teaching young people about sexualised deepfake abuse, alongside intersections of power and privilege, empathy, and the importance of sexual agency and consent, is more likely to bring about lasting change to prevent this form of non-consensual objectification of others.

We need to accept that social media and technology are a part of how young people interact. It’s therefore crucial to collaborate with young people rather than cut them out of the conversation.