This is the story of a tree that is much, much more than just a tree. It’s also the story of how Indigenous Australian culture can be honoured, reciprocated and deepened.

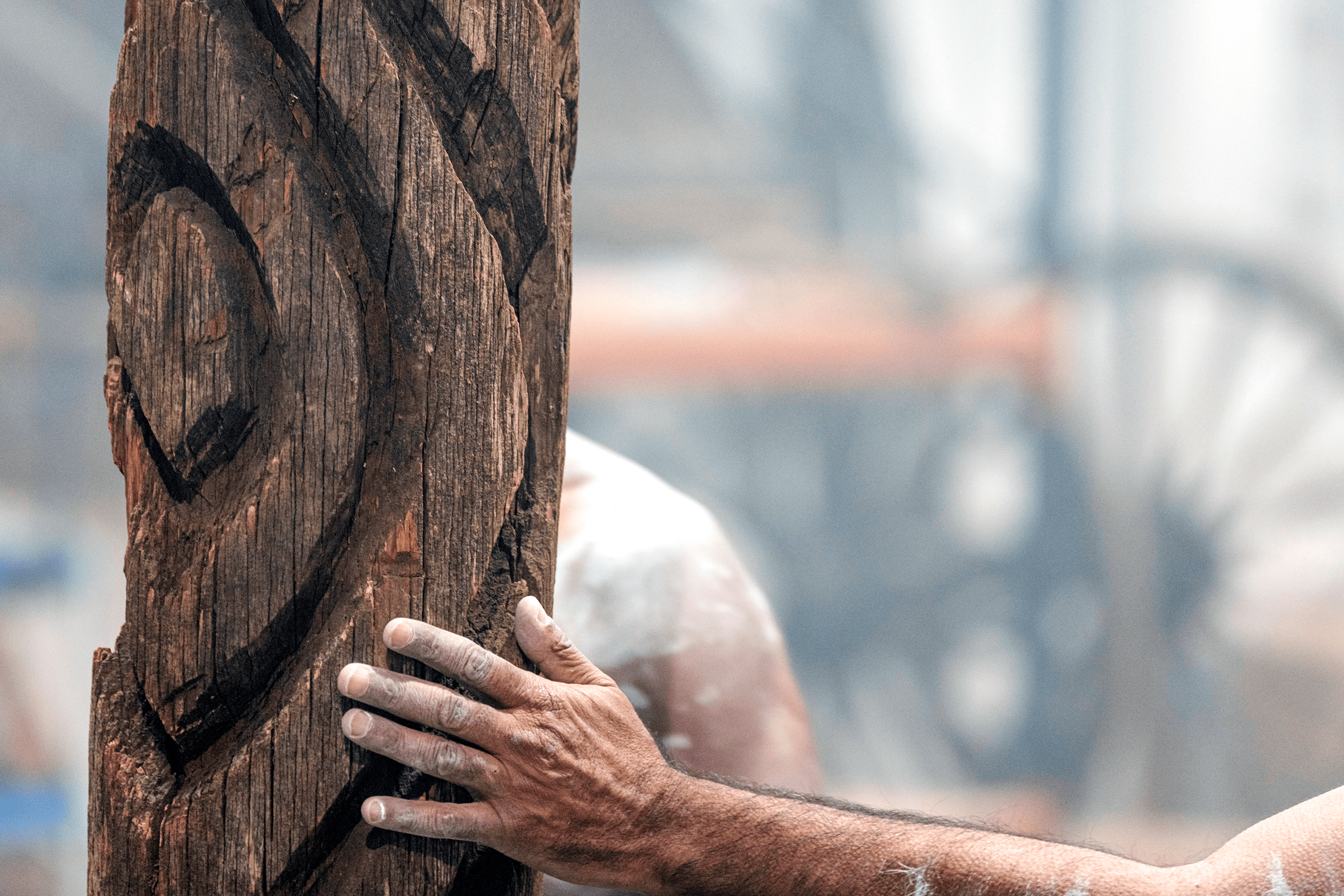

The tree is a thulu (dhulu) for the Gamilaraay people of New South Wales – an ancestor and family member who holds knowledge and can enact that knowledge for the community.

Ancestors are in the ground, and in the sky, and in Country, and trees play a vital part in the relationship between people and Country.

Yet this dhulu was taken away, and in this way is emblematic of Australia's ongoing struggle with its past in which origins can be absent, totems and symbols removed, families broken up, knowledge repressed, and culture stolen or otherwise removed.

The dhulu got to Switzerland, a long way from home, and has been there for nearly 100 years. However, it came to be looked after and honoured by a museum in Basel, the Museum der Kulturen (Museum of Cultures), and, after a long collaboration with Monash University and the Gamilaraay community, this week returns to Australia.

In a profound gesture, Gamilaraay community representatives have responded by gifting the museum a newly-carved dhulu, replicating the designs of the century-old dhulu as closely as possible, thereby signifying the community’s wish that Gamilaraay culture continues to be shared with Switzerland, Europe and the world.

A profound relationship

The museum’s director is Dr Anna Schmid. She says this dhulu and the extraordinary relationship that has developed between her institution and Monash University is profound – “… the unbelievable idea that something was taken without consent and when it is returned, a counter-gift is a given,” she tells Lens.

“I think that, in a way, the dhulu set the conditions for the relationship – calm, patient, waiting, and yet determined."

Professor Brian Martin, of Monash Art, Design and Architecture – a practising artist and scholar – and Gamilaraay Elder, Greg Bulingha Griffiths, have led the rich project to integrate the dhulu and its context within the museum in Basel, thereby creating a cultural relationship between it, Monash, and the problematic question of cultural materials and Indigenous history relating to colonialism.

The dhulu has been installed at the Museum der Kulturen since September last year as part of an exhibition titled Everything is Alive: More than human worlds. Professor Martin and PhD candidate Bradley Webb were invited to contribute Indigenous work for the exhibition – a catalogue essay, panels of drawings, and a short film.

The complex question of displacement

Professor Martin, Bundjalung, Gamilaraay and Muruwari, is the director of Wominjeka Djeembana Indigenous Research Lab. His art and scholarship is entirely about Indigenous perspectives and Indigenous peoples’ relationship with “Country”.

“Displacement is removing something from its place,” he says. “How does it return back to place? It's really complicated. And if it's something that’s originally been in the ground, but has been removed from the ground, and has been objectified and put in a museum, that journey is very complex as well.”

Read more: Indigenous science can help solve some of the great problems of our time

The dhulu in question has been in the museum for 80 years, which is equal parts fascinating and horrifying to begin with. It doesn’t belong to anyone in Switzerland, or their ancestors, or spirits. It belongs specifically to Gamilaraay men, and more generally to Indigenous Australia.

Yet, Professor Martin has a compelling view that “objects” (for Gamilaraay the dhulu is not an object, but a being) stolen or removed from Country by others should not be snatched back. Rather, it should be a medium or conduit towards learning and understanding.

“Instead of just going there and taking it back,” he says, “is a semblance of violence, the way it was taken away in the first place. So we wanted to have this more relational way of exchanging cultural practices.

“That way the story doesn't end. Museums have this fear of becoming empty, but this is a reciprocal exchange.”

Further support for the return of the dhulu was provided by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). At the request of the Gamilaraay community, the century-old dhulu will be temporarily held at AIATSIS in Canberra, until the community is ready to receive it on Country.

Continuing the narrative

The dhulu’s return to its home in New South Wales, while welcome and significant, is also challenging, he says. The act of repatriating the dhulu will become the basis for further artworks, including 3D models, while the rest of the dhulu exhibition remains. There will also be what the Museum calls a “counter-gift”.

“So it is replaced, in a way, and we continue the narrative,” says Professor Martin. “What that does is locate us in there here and now. We’re not lost in the ethnographic past. Museums can as a rule do that – locate us in notions of the past and the primitive. Whereas this is a contemporary articulation of culture and tradition.”

Read more: It’s time to listen to Indigenous peoples’ knowledge – but how do you do that?

Greg Bulingha Griffiths is in discussions with his community about where the tree might go once back on Country.

He and Gamilaraay representative Wayne Griffiths Jnr say: “It represents more than just an artefact coming back; it’s a reconnection to our ancestral heritage and the teachings that have sustained our community for thousands of generations.

“The dhulu carries the stories, values, and wisdom of our ancestors. Having it come back to its homeland by the Namoi River brings a sense of healing, as if a long-separated part of our heritage is finally returning to where it belongs.

“For our community, it reaffirms our resilience, our identity, and the continuity of our culture that has endured for over 80,000 years.

“It’s a powerful feeling to know that our children will grow up with this piece of their history close to them, and that they will see a symbol of resilience, rather than loss.

“The gifting of a new dhulu to the Basel Museum is a gesture of gratitude and respect for the partnership that has allowed the original dhulu to return home. This reciprocal arrangement emphasises that collaboration between museums and Aboriginal communities is not only possible, but mutually beneficial.”

The missing piece of the puzzle

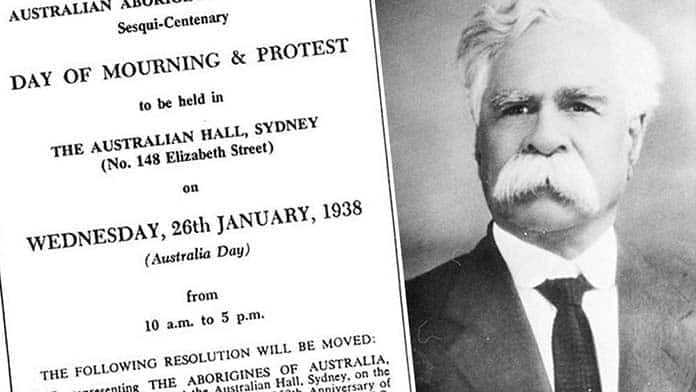

The tree's full story is incomplete, but we know it was in the Australian Museum in 1939 when it was bought by young Swiss writer and “ethnographer” Lucas Staehelin, from Basel, who was travelling around the South Pacific and Australia buying items. He and fellow adventurer Theo Meier also excavated graves. Staehelin also got his hands on a canoe, paddles and an axe.

Staehelin returned to Basel with his Australian bride, and the materials ended up in the Museum der Kulturen – which, all these years later, has a much more enlightened and inclusive response to Indigenous materials than many other institutions.

In 2021, The British Museum – viewed as the main colonial villain in the Indigenous cultural materials space – itself found 38,400 “objects” in UK and Irish institutions.

The Queensland state government this year committed $4.6m to help repatriate items, and the Queensland Museum is negotiating with the British Museum over First nations’ cultural materials – a negotiation hindered by an arcane British law from the 1960s that largely prevents museums from, as SBS/NITV reported, “disposing of their holdings”.

The British Museum was forced into an internal review after questions were raised about its documentation of objects in storage.

Telling families’ stories

The dhulu was once part of a group of carved river red gums on the Brigalow Creek, associated with a ceremonial ground near the small town of Boggabri. The markings are associated with specific families, tell their story, and lend them a voice.

“We need to do more research into how the tree got to the Australian Museum,” says Professor Martin. “That's the one part of the narrative we don't know."

Dr Schmid says she couldn’t have imagined how the restitution of the dhulu would turn out. “The dhulu stands even more for the relationship that has developed between members of the Gamilaraay and us, a relationship that is characterised by respect and seriousness, but also by humour and affection.

“It’s also a kind of memorial to the fact that we should generally become much more sensitive towards people, subjects and things.”

She says the tree basically spent 84 years in a Swiss cupboard, and is “probably the saddest episode in the life of dhulu. He spent most of his time in the storage – little-noticed and completely unrecognised in his importance.”

Dr Schmid – who describes Professor Martin as “multifaceted, considerate and thoughtful … he will always be most welcome here” – says in the end the Swiss exhibition in her museum and the wonderful sequel it has given the Gamilaraay and their dhulu – and her museum – is about injury and trauma, but also the possibilities of new relationships within the sphere of “cruelties and ignorance towards local cultural values”.

Perhaps the singular question is to do with museums themselves. What is their future, what is their exact role now?

“This is a cry for our history,” says Professor Martin, “in both the negative and positive senses. I think this whole process with Basel can really show how to shift museum practices.”