Last month, Australia’s newly-appointed Minister for Emergency Management, Senator Jenny McAllister, and Senator Tony Sheldon, Special Envoy for Disaster Recovery, took part in a cultural burn outside Lismore in New South Wales, as part of the National Gathering on Indigenous Disaster Resilience.

It was significant to see members of the federal government listening to and taking direction from a cultural burn expert, Oliver Costello, of Jagun Alliance, before undertaking a burn.

It represented a hopeful sign that cultural burning might be increasingly used as a tool for disaster mitigation. After all, McAllister isn’t the minister for Indigenous affairs or the environment – her role is emergency management. At last month’s meeting, Indigenous peoples spoke of their desire and inherent right to be involved in disaster management.

Cultural burning is, of course, vitally important to culture. But these gentle, regular burns were one of the main ways Indigenous groups managed land. They created mosaics of burned and unburned land, reducing the chance of megafires by burning fuel loads and creating safe havens in dangerous times.

Networks of Indigenous groups have begun using fire to once again care for Country all around Australia. These are positive signs. But there’s more to do to dismantle remaining barriers to mainstreaming cultural burning – and making it possible to use these ancient techniques to reduce, or avoid, disasters.

An ancient practice rekindled

The evidence of Indigenous land management using fire is significant and growing.

This evidence has emerged through formal truth-telling processes such as Yoorrook, whose commissioners heard about the deliberate suppression of Indigenous land management in Victoria.

It has come from ongoing academic research stitching settler accounts of the land and observations of how Indigenous groups used fire. In 1802, for instance, the settler John Murray recorded his amazement at how Boon Wurrung people set and controlled fire in Victoria’s Western Port Bay. The fire, which “must have covered an acre of ground”, was “dous’d […] at once”.

In Mary Gilmore’s account of 19th-century colonial life in the New South Wales Riverina, she writes:

“As to fire, it was [Indigenous people] who taught our first settlers to get bushes and beat out a conflagration […] Indeed, it was a constant wonder, when I was little, how easily [Indigenous people] would check a fire before it grew too big for close handling or start a return fire when and where it was safest.”

These historical observations are complementary to the work of passing on knowledge of fire to the next generation. Taken together, they reveal a fundamental truth about Australia – it is a land of fire, and Indigenous people are the masters.

The return of parcels of land to Indigenous groups in recent decades means we can restart these ancient fire regimes, through Indigenous rangers and other organisations.

The return of ancient practices

The management of land over deep time by Indigenous groups has meant people and the land effectively co-evolved.

Since 1788, colonisation and Indigenous dispossession have radically altered many parts of Australia. Land was cleared for farms, cities, roads and infrastructure. Rivers were dammed for irrigation.

Grasslands and yam fields were converted to livestock farms or cropping. Forested areas in some areas were cleared and in other areas thickly regrew, replacing the park-like mix of grassland and stands of trees produced by Indigenous land management. Thirsty crops such as cotton were planted, siphoning off huge volumes of water from lakes and rivers.

Even the creation of national parks transformed landscapes, as Western practices of more passive management replaced active Indigenous management.

The suppression of cultural burning brought yet more difficult change to Australia’s plants and animals. Australia now has one of the highest extinction rates of animals in the world. But cultural burning is being applied as a method to help protect vulnerable species, such as the Corroboree Frog.

Over years, Indigenous groups have worked diligently and strategically to rekindle this ancient practice. But they have also reimagined it. It’s time to ask the question: What would it mean to bring back cultural burning at scale?

No longer do Indigenous groups apply fire as a normal and everyday rhythm of life, stopping to light small fires as they walk. It’s now much more deliberate, requiring careful planning, creation of fire breaks, and management of fire using trucks and heavy machinery.

Even ignition is done differently. For a ceremony, firesticks will be used, with further lighting done using drip torches. In remote areas, fires are lit from helicopters, making it possible to cover vast areas.

Combining these ancient and contemporary practices creates something fundamentally new. We require innovative discourses to better describe these developments.

New fire season, new hazards

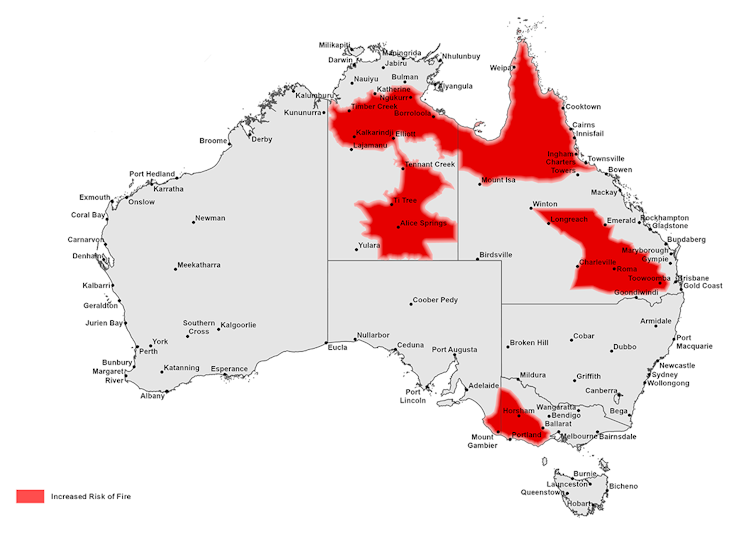

This fire season is likely to be a dangerous one. The seasonal bushfire outlook released by the Australasian Fire and Emergency Council projects the risk of early fires and a higher-than-usual bushfire risk over vast areas of Australia.

Recent rainy La Nina years triggered rapid vegetation growth in many areas, increasing the fuel load. Fire authorities are worried about what a forecast hot, dry, windy summer will mean.

In recent years, Indigenous ranger groups have been undertaking cool burns as much as possible. In arid areas, there are fears of fast-moving grass fires due to the spread of introduced and highly flammable buffel grass.

As danger from climate change intensifies, making volatile and combustible landscapes safer poses challenges both complex – and urgent.

Indigenous groups around Australia have begun the work of rekindling cultural burns, but barriers still remain. Responsibility for fire management in state forests, national parks and on private land has long been split between government authorities and landholders. It’s time this disaster management work by Indigenous groups was recognised and magnified by governments.

To mainstream cultural burning will mean finding ways of sharing the knowledge of when and how to burn, and resourcing Indigenous groups to undertake training and burns. Doing this will not only benefit the land and Indigenous groups, but all Australians.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Monash is pioneering a path to a greener, smarter, more equitable and sustainable future, where emissions are lower, and the natural environment and humans thrive. We look forward to participating at COP29, where we aim to accelerate global action on sustainability, empowering diverse voices from across the Indo-Pacific and influencing superior policy outcomes across a broad range of issues. Find out more monash.edu/cop29