In early-’60s London, a young Australian actor and satirist named Barry Humphries accepted a commission to write a comic strip that was to change his life.

Peter Cook, editor of the satirical magazine Private Eye, asked the young expat to aim his barbed wit at the hordes of other young Australians crowding into the west London neighbourhoods of Earls Court and Notting Hill.

Barry McKenzie, a young, uncouth innocent abroad, was born.

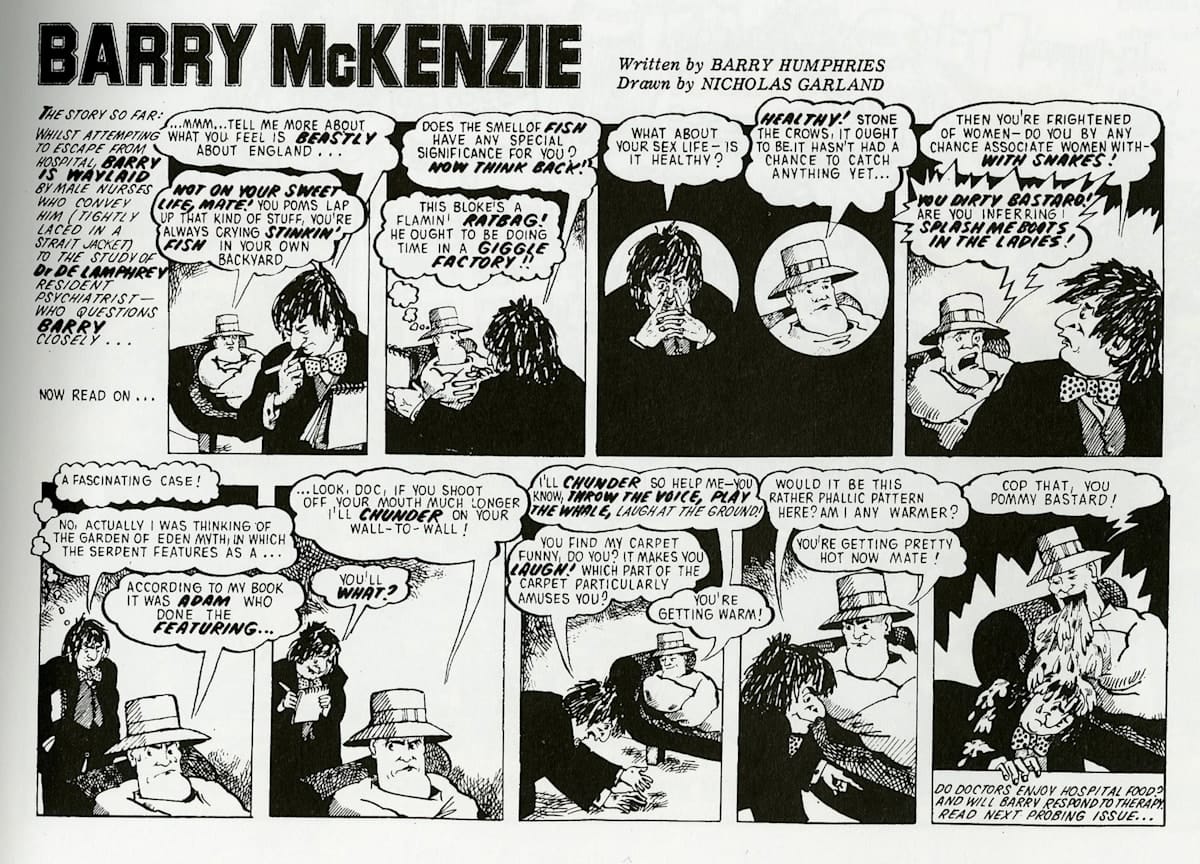

Drawn by New Zealander Nicholas Garland, the cartoon Barry McKenzie looked like a cross between Chesty Bond and the Jolly Swagman, dressed in a 1950s double-breasted suit screwed down with a wide-brimmed Akubra hat that never left his head.

“Bazza”, was vulgar and irrepressible, perpetually sucking on “ice-cold tubes of Fosters”, trying unsuccessfully to get “a sheila into a game of sink the sausage”, and ”chundering” on unfortunate “Poms” who crossed his inebriated path.

He allowed Barry Humphries to have a spray at everything he disliked about Australia and England. The strip became a cult hit in Britain.

In Australia it was banned. Against the odds, though, it was made into two early films of the 1970s Australian cinema revival, both directed by Bruce Beresford in close collaboration with Humphries. Liberated by the new R certificate, Barry McKenzie had gone from smuggled contraband to national carrier.

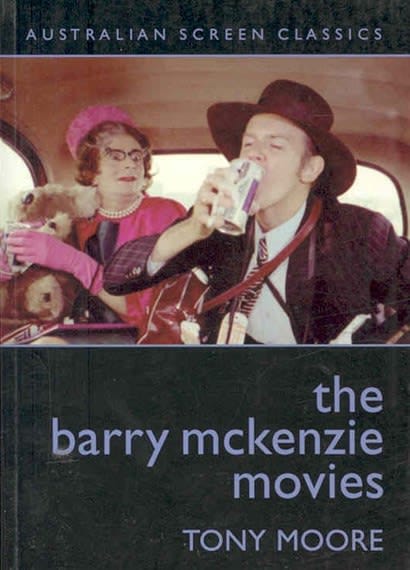

The movie was a commercial smash, showing that Australian films could hold their own at the box-office against Hollywood and British flicks.

But most Australian critics hated it. What would people overseas think? The Age fretted that such a film “would only serve to confirm the world’s suspicions that we are a Wake in Fright nation of Bazzas and Storks”.

The ubiquitous cultural critic Max Harris despaired that modernists from an earlier generation like him had fought for cosmopolitanism only to have these philistine Ockers drag Australia back into the 6 o’clock swill. For these insecure sophisticates, the convict streak was exposed to the world like a grimy stain on the national underpants.

Barry Humphries and Barry Crocker, The Adventures Of Barry McKenzie, That's TV (Sky 171, Freeview 65), 11.45pm. pic.twitter.com/icKsWqEWpO— Richard Luck (@RMGLUCK2017) May 29, 2023

It’s difficult to believe that as a teenager I was allowed to show Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, the 1974 sequel to The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, at my high school.

Today, with lines such as, “I’m that randy I could root the hair on a barber shop floor”, it would ring alarm bells and end careers. But the ’70s was another country – we did things differently there.

What we schoolboys knew was that this film, with its ribald humour, inventive Aussie slang, great songs, slapstick, beer, vampires, and kung fu fights, was a riot. And who could doubt that Holds His Own was “a bloody good cultural show”, to quote one of its characters, when the prime minister himself, Gough Whitlam, made an appearance?

I consider these films to be two of the funniest comedies ever made in Australia. But they are much more than low Ocker farce, for its creators set out to critique society and to shock audiences.

By fusing ideas from the artistic fringe, especially Dada, with popular local traditions of larrikin subversion and music hall, Humphries and Beresford created something recognisably Australian, yet entirely new and surprising.

Barry Humphries is a contradictory artist. An aesthete attracted to “decadents” and dandies such as Oscar Wilde and painter Charles Conder, he’s intrigued by the low-life and vulgarity.

A sophisticate who despaired of suburbia, Humphries’ comedy revelled in parodying the prejudices and ignorant certainties of old Australia, while equally puncturing the pretensions of the new.

He eschewed the elitist pretensions of a Patrick White for the roar of the crowd, appealing to popular taste via the mass media. An abstinent alcoholic, he made a film in which beer is the elixir of life. A bohemian, he adopts the mask of the Ocker.

Like many expats and travellers before and since, Humphries was disillusioned with the England of his dreams. As is apparent in his memoirs, Humphries found the pompous and self-congratulatory tone of much British satire smugly elitist and pretentious, and gave the genre a levelling Australian inflexion.

In the strip and films, the lower-class Barry McKenzie is a type of truth-telling fool, a satire not just on boorish colonials in the metropolis, but a foil against British complacency and condescension.

The UK is depicted as degenerate and squalid, its people grasping and craven. Barry has a succession of encounters with English men and women who alternatively want to fleece, promote, exploit, shag, marry, psychoanalyse, arrest or fight him (and occasionally several of these at once). Our hero leaves mounting chaos in his wake, climaxing in the exposure of his “old fella” live on a BBC TV program about the artistic renaissance in Australia.

In crooner, cabaret artist and popular TV personality Barry Crocker, the cinematic Barry McKenzie was gifted charm and charisma. However, Barry Humphries is everywhere as multiple characters in both films. These include psychiatrist Dr De Lamprey, an amalgam of every shrink Humphries had ever endured; sleazy hippie conman Hoot; philistine Labor arts minister Douglas Manton; and, of course, Edna Everage.

It was Beresford’s idea to include Edna Everage, who had never been part of the comic strip, and it was an inspired decision.

As fussy Aunty Edna chaperoning her wayward nephew through the temptations of swinging London, Humphries introduced a respectable Melbourne foil for Bazza’s Sydney working-class larrikin, while cutting through British pretensions in her own lemon-lipped way.

In fact, Edna’s over-the-top presence in the movies is the catalyst for her 1970s transformation from a frumpy tutt-tutting housewife into the caustic purple headed-pantomime dame taking aim at celebrity culture itself.

Barry McKenzie Holds His Own had a much bigger budget, and is in many ways a more edgy film than the original. “Tinnies” are hurled at grant-laden artists, philistine politicians, blow-hard bureaucrats, zealous radicals, and especially smug trendies.

Bazza’s “Pommy Bastards” t-shirt of the first film is now replaced with “Commie Bastards”! The political edge is explicit in the film’s sustained satire of ”The Australian Cultural Renaissance”. As Barry McKenzie explains:

“The government’s shelling out heaps of moolah for any prick who can paint pichers, write pomes or make flamin’ fillums’ … We’ve got culture up to our arseholes.”

Looking back at this now, it seems to me any renaissance worth having is one where the artists laugh at themselves, and where the Pericles at the centre of it all, Gough Whitlam, is a good enough sport to join in on the joke, appearing at the film’s end to Dame Edna Everage.

To quote Gough in a fax he sent me addressed to Bazza McKenzie, but intended for Humphries:

“My Government did not believe in conferring titles, but I personally and spontaneously decided to make an exception in Edna’s case in May 1974. A couple of weeks later my Government was re-elected. It was the first and last time that Dame Edna supported Labor. My only regret is that I advised Her Majesty to appoint Sir Les as Governor-General.”

#OnThisDay Prime Minister Gough Whitlam stars as himself in a scene being shot at Sydney Airport for the film "Barry McKenzie Holds His Own", April 20, 1974. He is pictured with Barry Humphries playing Edna Everage. Photo by Trevor Dallen @smh @photosSMH #auspol pic.twitter.com/U6NuabJPyi— From The Archives (@AgeSMH_Archives) April 20, 2018

The films were emblematic of the so-called “New Nationalism” associated with the Gorton and Whitlam governments.

Bazza, his “one-eyed trouser snake” at the ready, also played his part in the permissive “sex ’n sin” atmosphere of the ’70s media, helping to free up what could be said and shown in our public art.

The banning of Barry Humphries’ comic-book compendium The World of Barry McKenzie became a civil liberties test case in 1969, and while they lost, it helped persuade the-then federal minister for customs, Don Chipp, to overhaul the law relating to book and film censorship.

The McKenzie films are important because they deal with key tensions in Australian culture, between the province and the metropolitan centre, the wowser and the libertine, authority and unruliness, cosmopolitanism and white Australia.

In a period of rapid social transformation in both Australia and the UK, Barry Humphries used the Ocker mask of Bazza to make what are still controversial comments on class, masculinity, sex, race, religion, art and politics.

The Barry McKenzie films have travelling at their core – travel across national borders, but also social barriers.

Barry McKenzie is peripatetic, rarely seen in his dreary bedsit, continually on the move in planes, shop-overs in Hong Kong, leaping in and out of taxis, boats, Kombi vans – a swagman in the age of global travel.

It’s a bit like the happily itinerant Barry Humphries, who clearly draws on his experience as a traveller and expatriate trying to make dual careers in Britain and in Australia. In his own words, Humphries is a “compulsive globetrotter” who always has “a ticket to somewhere”, “without ever being sure where I belong … never quite sure what is abroad”.

Asked in flight by a backpacking Australian, “What route are you taking?”, Bazza answers, “No one – I’m travelling with my Aunty Edna”.

Some of the funniest scenes emerge from Barry’s difficulty at crossing borders, falling foul of a customs official at Heathrow, thrown out of the UK for disgracing himself on national TV, being smuggled back into England from France on a tugboat disguised as an Arabic refugee, parachuted into an Eastern Bloc people’s republic.

Barry crashes through social barriers, too, running the gauntlet of a young conservative ball, (unsuccessful) interracial sex, impersonating a clergyman (to give a sermon on Christ and the orgasm), and a cross-dressing farce where Barry in drag is pursued from a gay pub by police.

Holds His Own is especially obsessed with the borders of race. The sequel shows a bunch of white men terribly anxious about other ethnicities, satirising the obstinate persistence of prejudice despite the ending of the White Australia policy. Today, the film’s preoccupation with borders, refugees, airport searches and migration control seems eerily topical, as it was in the 1970s.

One of the biggest challenges facing Australians emerging from White Australia was increased diversity through immigration. Humphries’ and Beresford’s satire picks at the scab of Australian racism, ventilating this running sore, suggesting that decades of prejudice were stubbornly persistent.

For me, the McKenzie films conjure an Australian larrikin version of the carnivalesque, where a topsy-turvy spirit of riotous festivity, misrule, ribaldry, profanity, vulgarity and sacrilege is deployed against authority and pomposity.

In this struggle, I’m on the side of Bazza, and believe the films’ hostility to power and position makes them radical, subversive and life-affirming.

At the turn of the century, I wrote an article for Strewth magazine seeking to resurrect Barry McKenzie Holds His Own in popular memory.

Barry Humphries immediately faxed and phoned me, offering tidbits and insights, and helping us bust the film out of the cobwebbed vault to which the producer, Grundy’s, had consigned it.

Unfalteringly generous with his time and advice, Barry provided a filmed introduction for re-release cinema screenings, and later checked and corrected the manuscript for my book on the movies.

Over the phone in his impeccably precise accent, he would explain matters of great import – for example, that the slang phrase to “cream your jeans” was not actually Australian; he’d picked it up from an American sailor!

Speaking on a panel with Beresford and Crocker to launch the book at Paddington RSL, Barry Humphries stole the show as himself, and impressed all assembled with his wicked gentlemanly grace. This included a very old Gough Whitlam, who left extolling the genius of McKenzie’s vernacular.

Despite its mockery of our many foibles, the McKenzie films cemented for me, and many in my generation, the idea that any Australian patriotism should be, first and foremost, based on taking the piss, of laughing not just at one’s self, but at the powerful, whether they be upper-class Brits, smug virtue-signallers, or the PM himself.

As long as we can produce a bullshit detector such as Barry Humphries, all is not lost.