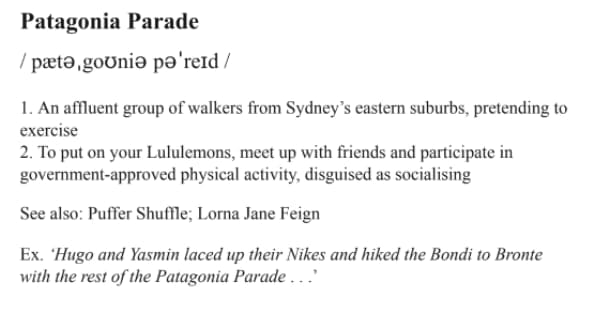

I’ve been enjoying reading Betoota-isms (2021), a guide to Australian slang, from the team responsible for (or should that be irresponsible for?) The Betoota Advocate.

Described as “a deep dive into Australian culture, invention and creativity with a complete record of ‘English’ as it is used from the Member’s Box of the MCG to the change rooms of the Betoota Dolphins rugby league club”, the work demands to be taken seriously.

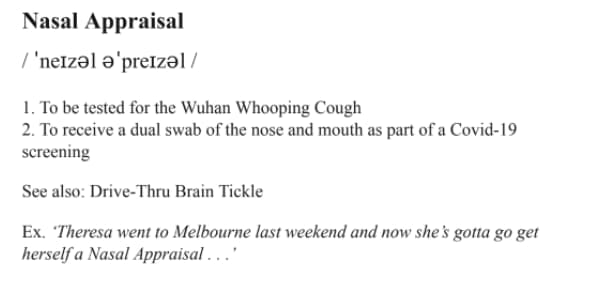

It includes phonetic transcriptions and examples of expressions in use, as you can see in these examples:

Surely the publisher is entitled to claim of this work: “As authoritative as the Macquarie Dictionary and as exhaustive as a Fortitude Valley pub crawl, Betoota-isms is your one-stop guide to the grandeur of the great Australian vernacular.”

But do those examples seem real? And why is it that neither of the expressions above yield relevant Google results? (This does vary with subject matter; expressions listed under “Australian Archetypes”, such as “Irish twins”, “Karen” and “bean counter”, are much better attested elsewhere.)

Read more: Getting on the grog: Plonk yourself down for a guide through Australian alcohol slang terms

I think the answer has been given already – this work examines “Australian … invention and creativity”.

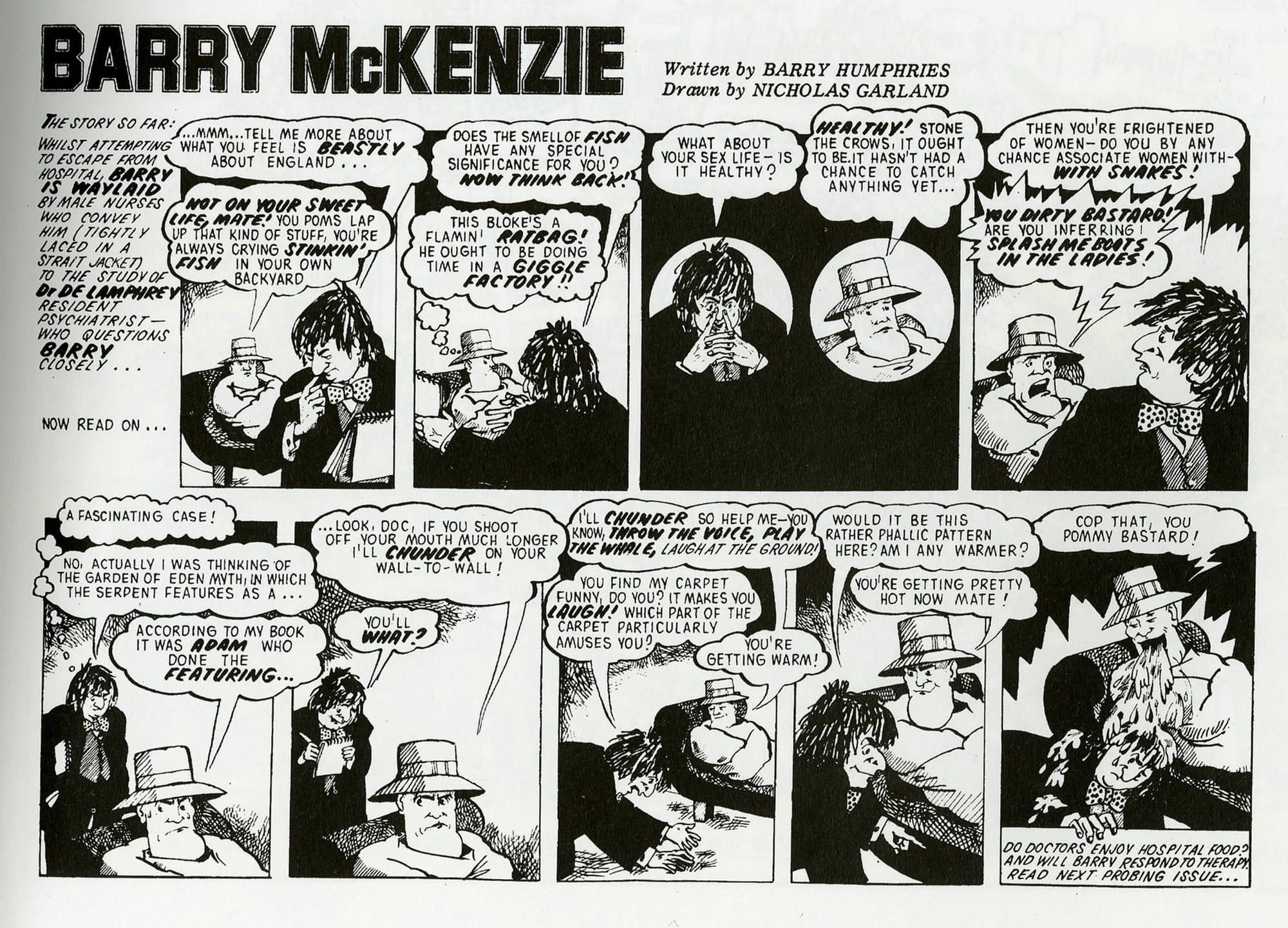

And in this, I think it’s part of tradition that certainly also includes the work of Barry Humphries. Did anyone use expressions such as “technicolour yawn” or “point Percy at the porcelain” before Humphries put them in the mouth of Barry MacKenzie?

In our research, we’ve identified a tendency to creative reuse of some constructions (such as “an X short of a Y” – see this piece by Kate Burridge), and what we see in the work of Humphries and the Betoota crew is a more performative extension of this.

If nobody is actually using these expressions, we nevertheless find it easy to imagine that a dinkum Aussie could use them.

Stalking Strine: The sounds and rhymes of people’s poetry

There’s another approach to vernacular language in Australian humorous writing that attempts to represent the sounds of Australian speech that are seen (heard?) as non-standard.

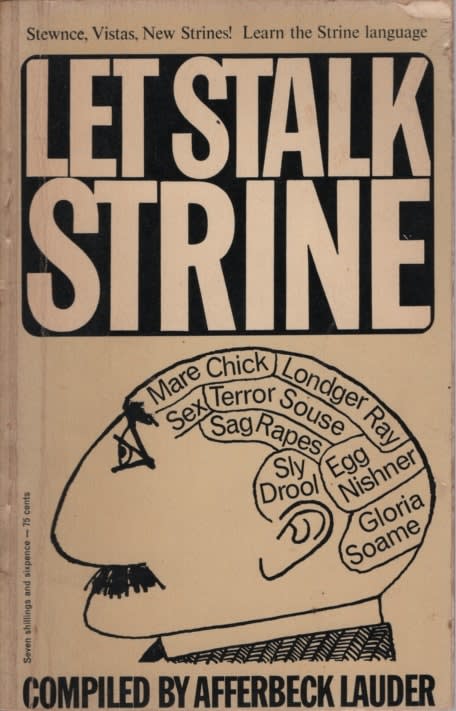

Examples of this include Charles Corbyn’s humorous accounts of the Sydney magistrates’ court of the 1850s, and Afferbeck Lauder (Alastair Morrison)’s books about Strine (Lauder, 1965).

Read more: Look, mate, I just wanna know the top Aussie slang term

Such writing is a continuation of a tradition for representing varieties of English that stretches back through Dickens at least to Shakespeare.

And as Kate and I have described elsewhere, the part of that tradition that provided a stereotypical representation of Irish speakers was imported to Australia wholesale.

But even the stereotypical version of Irish speech is based on observation, drawing attention to, for example, differences in vowel quality, and a different pattern of consonants.

In contrast, the humorous writing about lexical inventions is much less based on data. As already noted, many Betoota-isms aren’t attested in Google searches, and the recourse to phonetics in that work is an appeal to spurious authority.

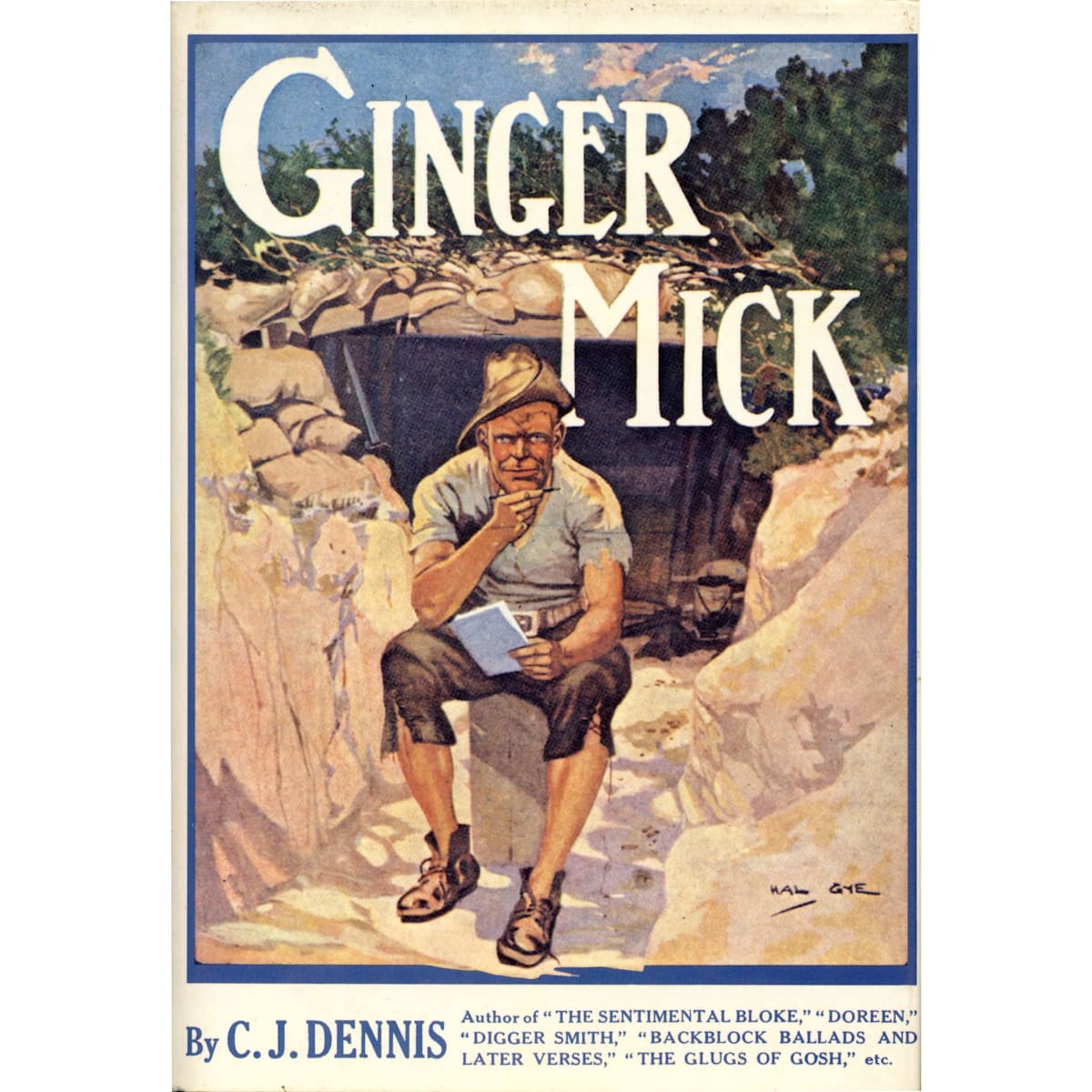

‘Jist to intrajuice me cobber, an’ ’is name is Ginger Mick’

The awkward question that these humorous lexicons raises in my mind is one about C.J. Denis and Ginger Mick. Records of actual speech from the early 20th century are limited, and we can’t really know whether anyone actually spoke using the expressions Denis puts in Mick’s mouth.

Is it possible that the language of Ginger Mick is as much a creative work as that of Barry MacKenzie or of a Betoota-ite?

Go to our website to catch up on other discoveries on the history and evolution of Aussie slang, and to comment on this article. We’d love your feedback.