Seven years ago, a prominent academic specialising in disaster medicine was invited to his birth country of Iran, from his adopted country of Sweden, to participate in workshops at Iranian universities.

Dr Ahmadreza Djalali would have known the risk he took – researchers, students and physicians, among many others, are routinely targeted by Iranian authorities because of perceived affinity with Western values, and have been since the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979.

Dr Djalali had been working and teaching at universities in Belgium and Italy, while living in Sweden with his wife and two children.

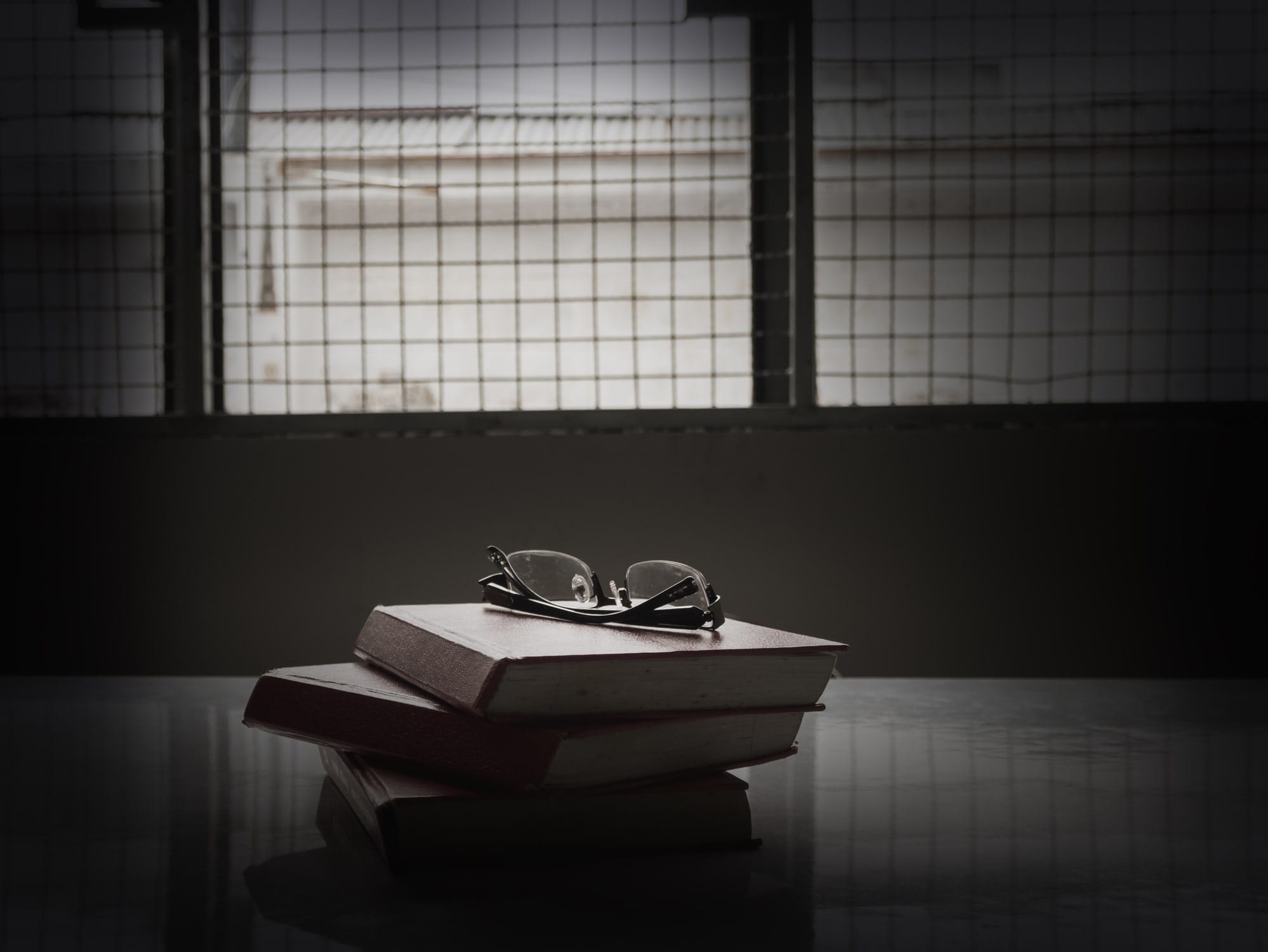

He made the trip, but was duly arrested for “collaboration with hostile governments” and “acting against national security”. He was put in Evin Prison, then convicted and sentenced to death without the right to appeal on a charge of “corruption on earth”.

Iran claimed he was spying on its nuclear capabilities for Israel, a claim without evidence. He then refused to spy for it on Israel.

The advocacy group Scholars At Risk, based at New York University, says in the past year alone there have been 13 instances of “killings, violence, disappearances of academics or students in Iran”, and nine imprisonments.

Real-world advocacy projects

In an Australian first, a third-year undergraduate unit in Monash Arts has been partnered with Scholars At Risk in real-world advocacy projects for imprisoned academics including Dr Djalali.

In the unit, “Activism for academic freedom: Applied workshop in research advocacy”, students are assigned a scholar, and create advocacy plans for them.

Student Elisa Salvador says it’s fulfilling to try for real change.

“With everything we know about human rights and everything we know about international studies, sometimes we get, as academics tend to be, quite stagnant,” she says. “We get tunnel vision, we talk about all of these abstract concepts without being able to put a finger to them.

“It's been really exciting to contextualise this, to really roll up our sleeves and see how we can actually do something practical for somebody who’s facing the death penalty. I think that it really goes along with Monash’s vision to ‘change it for good’.

“So we're the first generation that has been invited to come along and take the unit. But I think that most of us have a deep regard for academic freedom, and it’s become a personal commitment towards Dr Djalali.”

Creating effective campaigns

The unit is a 12-week exercise to create an effective advocacy campaign to support Scholars At Risk in their quests to free or better the conditions of the hundreds of academics in, at the moment, the Middle East, Russia, India and Brazil.

Scholars At Risk monitoring “identifies six attack types: killings/violence/disappearances, wrongful imprisonment, wrongful prosecution, travel restriction, loss of position, and other severe or systemic attacks”.

It can also arrange temporary research and teaching positions at linked institutions.

Salvador’s group – with Jessica Oats and Stella Parkinson – asked for help from Kylie Moore-Gilbert, the British-Australian political scientist from the University of Melbourne who was imprisoned in the same jail as Dr Djalali, for two years, in solitary confinement. She was released on a prisoner-swap/hostage diplomacy deal in 2020 – two Iranians in a Thai prison over terrorist bombing charges, for her.

Dr Moore-Gilbert shared a cell for a time in Evin Prison with Iranian conservation biologist Niloufar Bayani, who is still imprisoned, with no dual citizenship to help her in hostage deals.

Bayani had worked for the United Nations. In letters from prison, she alleges physical and psychological torture and sexual threats.

Dr Moore-Gilbert speaks at a free panel event organised by the students at Monash’s Caulfield campus on 18 October; Dr Djalali’s wife is speaking via video message at the event.

Jail tied to hostage diplomacy

Dr Djalali, meanwhile, is very sick. Scholars At Risk say he’s been denied healthcare for a range of chronic conditions, including leukemia and depression.

Stella Parkinson explains his imprisonment is deeply tied to hostage diplomacy because of his Swedish citizenship.

“The regime hoped to swap him for an Iranian official that was being held in Sweden,” she says, “but Sweden sentenced this Iranian official to life in prison, and that’s when Iran announced they’d be executing Djalali, which was meant to happen in 2022.

“Through actions from organisations like Amnesty International, this date has been continually pushed back, but it could be tomorrow for all we know. It’s awful; I can’t imagine what he or his family must be going through. It really feels like you're part of something bigger than an assignment.”

It gets disheartening, says Salvador, “but it’s practising global citizenship – the fact that we’re able to hold a flashlight to this abuse and make sure that the world is watching, and that there’s people aware of this.”

The unit has seen them in contact with Scholars At Risk groups running advocacy campaigns. They’ve created a social media toolkit for Dr Djalali, and negotiated with their faculty about cooperation and involvement in the upcoming panel event, as well as a fact-checked letter-writing campaign to governments and beyond.

Their efforts have paid off, with successful contact with established activist groups such as Melbourne for Iran, Feminista, and Amnesty International, who are all supporting the panel event. The event will be covered by international media and streamed live for maximum outreach.

“Our degrees are obviously very theoretical,” says Jessica Oats. “So actually seeing how things in our field of study exist in the real world, and how they interact with real people and have real consequences has been fulfilling and so important in the long term.”

Tickets for their free panel event are available here.

.