It was Robert Menzies, father of the modern Liberal Party, who famously remarked: “To get an affirmative vote from the Australian people on a referendum proposal is the labour of Hercules.”

Menzies knew this from bitter experience. The politician with the electoral Midas touch was the sponsor of three unsuccessful referendums. Most notable was Menzies’ (thankfully) failed 1951 attempt to win public support for amending the constitution to grant his government the power to outlaw the Communist Party of Australia.

On the Labor side of politics, the feat of constitutional change has been an even more unfulfilling exercise. The party has been responsible for 25 amendment proposals, and only one has been successful. It has been a truly Sisyphean quest.

If the opinion polls are to be believed, history is repeating itself with the impending Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament referendum.

Since the middle of the year, those polls have been relentlessly moving in the wrong direction for the “yes” case. On the current trajectory, the Voice will secure less than 40% of the national vote and also fail to win the support of a majority of states. The frontier states of Queensland and Western Australia in particular are lost causes.

Read more: Labor and Albanese recover in Newspoll as Dutton falls, but the Voice's slump continues

As it must, the “yes” camp continues to evince optimism. Its advocates point, for example, to the relatively high number of undecided voters, hoping they break heavily in their favour. I fervently pray this optimism is well-placed.

Yet a prudent government would now be wargaming what to do in the scenario that the Voice is defeated on 14 October.

For Anthony Albanese, a “no” vote will present diabolically difficult challenges. As Prime Minister, he’ll be tasked with making sense of that result. His response will need to be finely calibrated, modulating the message to different audiences.

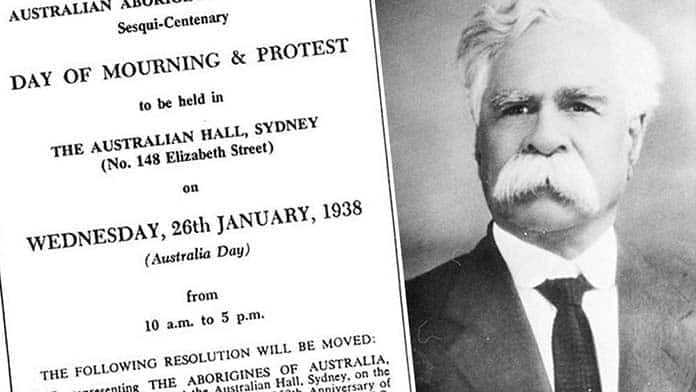

First, and most importantly, he’ll have to devise a formula of words to console and soothe the Indigenous population, the majority of whom will likely feel the rejection of the Voice is another in a long line of acts of dispossession and exclusion by settler Australia.

Albanese has often likened the Uluru Statement from the Heart to a generous outstretched hand. He’ll not only need to explain why that hand has been spurned, but give cause why First Nations people should continue to keep faith with non-Indigenous Australia. He’ll have to provide reassurance that reconciliation endures as a genuine project.

Read more: Voice to Parliament: Debunking 10 myths and misconceptions

Both at home and abroad there will be those who view a “no” vote as having exposed a dark streak of racism in Australia’s soul.

Albanese will feel obliged to seek to absolve the nation of that stigma. But given some of the more noxious attitudes aired during the referendum campaign, airbrushing racism out of the picture will not be easy.

On election nights, leaders are typically magnanimous in victory and gracious in defeat. There’s a convenient myth about election results – that the punters always get it right. Albanese will no doubt have to publicly give lip service to that notion if the referendum fails. He’ll avoid recriminations, despite the sophistry and mendacity that has characterised the “no” side of the debate.

In this way, he’ll play the role of healer-in-chief after the bitter divisions of the referendum campaign. What attacks there are on Peter Dutton for being a wrecker will probably be left to be made by other government members, but even these will have to be carefully framed so as to not indict all those who fell in behind the “no” cause.

The larger dilemma Albanese and his government will face if the referendum is lost is where to next with the Uluru Statement agenda, to which the PM signed up lock, stock and barrel on election night in May 2022.

Most pressing will be the question of what happens to the idea of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. The most obvious fallback position will be a legislated rather than constitutionally enshrined Voice.

The complication is that Dutton has claimed some of that space, and Indigenous leaders have rightly portrayed a legislated Voice as a poor substitute because it can be repealed by a future government. Somehow a legislated Voice will have to be transformed into a palatable alternative.

The Voice was the low-hanging fruit of the Uluru statement when compared to treaty-making. The realpolitik takeout from the rejection of the Voice referendum will be that there is next to no chance of delivering on a national treaty in the short to medium term, especially if that were to involve some form of constitutional amendment.

It would provoke an even more shrill scare campaign than the one we’ve endured over the Voice. In the absence of progress at the national level, it will be left to the states to advance treaty making and truth-telling.

Read more: What actually is a treaty? What could it mean for Indigenous people?

The defeat of the Voice referendum may set back other elements of Labor’s vision for the nation. When he won office, Albanese appointed an assistant minister for the republic in a clear signal that a move to a republic would be a feature of his government’s longer-term reform program.

With the Australian public’s profound reluctance to embrace constitutional change demonstrated yet again, it will likely douse enthusiasm within the government for proceeding to a referendum on a republic in its second term. The idea will continue to drift, as it has since 1999.

Another probable consequence of the loss of the referendum will be a narrowing of the priorities of the government. Labor hardheads will read that result and opinion polls showing a dip in the government’s support as evidence that voters are growing frustrated by what they regard as a straying from bread-and-butter issues.

So, we’re likely to see a less expansive government as it steers towards focusing chiefly on matters such as the economy, cost-of-living pressures and housing shortages. These, of course, are vital issues, but they’ll not stir the soul or etch themselves into history as would a Voice, treaty and republic.

All of this seems a desperate shame. But it is the Australia we’ll wake up to the morning after 14 October , if indeed the referendum goes down.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.