I am Jacinta Walsh, Jaru/Yawuru woman, mother to three young men, and a PhD candidate and research officer with the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre.

I am an adoptee raised in a non-Indigenous family, away from Country and Culture. In 1998, I approached Link-Up and began the journey of reconnection with my birth mother, of Irish heritage, and my birth father, a Jaru man from Western Australia.

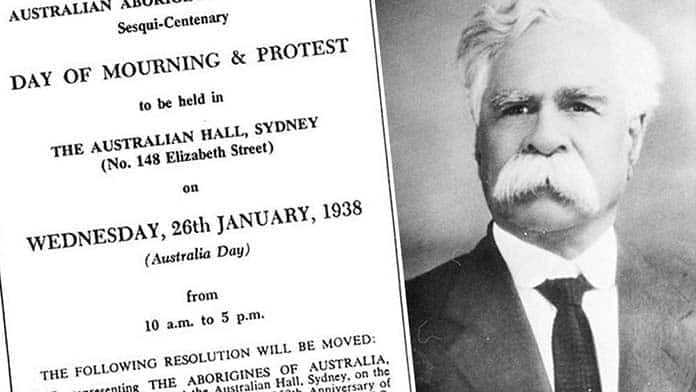

Historically, the colonisation of Australia has been told as a success story, with little reflection on how this narrative has influenced Aboriginal women, children, and their families.

My research directly challenges this problem.

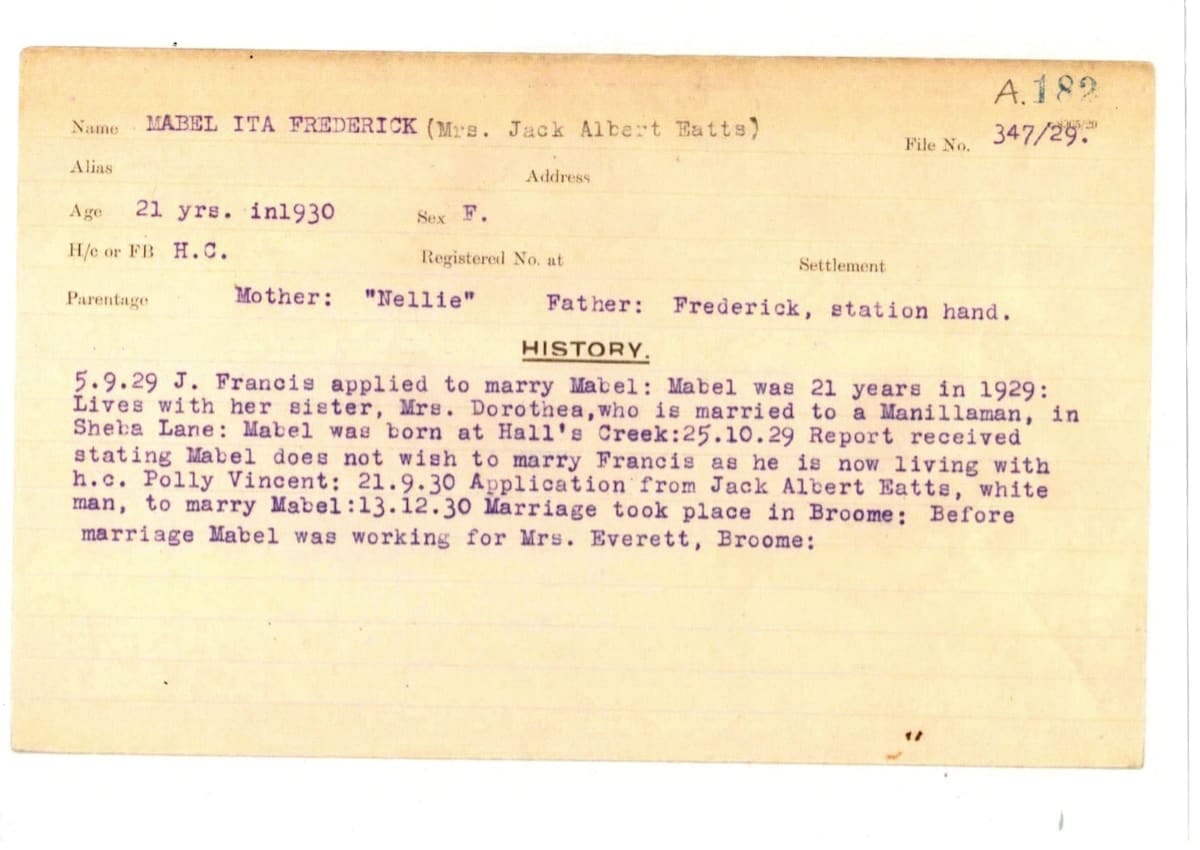

I am writing a “living oral history” that honours the life of my great grandmother, Mabel Ita Eatts, née Frederick (1907-1991). Through access to all the archives available to me, I’m telling a story of connection and healing, through relational understandings that the past lives in our present.

I advocate for First Nations’ family standpoints inside the University, Indigenous access to archives that relate to them, and processes of culturally-informed intergeneration truth-telling and healing through story.

This year, Australians are being asked to decide if our First Nations’ peoples should have a constitutionally recognised say in decisions that affect them.

Energies in public and private spheres are palpable. In the community, I hear everything from fear, hate, uncertainty, certainty, trepidation, excitement and, for many, a sense of hope.

I’m finding it overwhelming, but rather than hide under a rock and wait for an outcome, which, I admit, I have been doing, I’ve decided to contribute to this important discussion.

After all, if I don’t speak up for myself and my family, then who will?

A voice unheard

In 1997, the then attorney-general of Australia, Michael Lavarch, in his introduction to Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, wrote:

“In no sense has the Inquiry been ‘raking over the past’ for its own sake. The truth is that the past is very much with us today, in the continuing devastation of the lives of Indigenous Australians. That devastation cannot be addressed unless the whole community listens with an open heart and mind to the stories of what has happened in the past and, having listened and understood, commits itself to reconciliation.”

This was a critical message for all Australians to hear, and it remains as relevant today as the day it was written.

The Bringing Them Home report gave voice to Aboriginal families and communities affected by Aboriginal child removal policies. The inquiry heard hundreds of heart-breaking testimonies offered by those once removed from their families, and from their descendants.

My Great Uncle Walter Eatts was one of them.

In a submission by the Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia to the royal commission, on pages 35-37, his testimonial reads:

“I think it is important for people to realise that it was not only the parents and children who were taken away from their parents who really hurt, but it is also the children of the children who were taken away who suffer. I just don't think people realise the consequences of removing children from their families.”

Despite the National Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples delivered by Kevin Rudd in 2008, and the National Apology for Forced Adoptions by Julia Gillard in 2013, Aboriginal children remain overrepresented in the out-of-home-care sector. There are currently more than 22,000 Aboriginal children living in out-of-home care, and the numbers are on the rise.

Colonialism and subsequent Aboriginal child removal and adoption policies and practices continue to have devastating and lasting impacts on many Indigenous people’s connections with their biological families and their ancestral homes.

For those of us who have been separated from family and Country, the journey to locate and to know our ancestry, and ourselves, can be a difficult one. It can take a lifetime.

Mabel’s voice

Mabel passed away in 1991, seven years before I reunited with my birth family. Mabel and the man she married, Jack Albert Eatts, raised six children, including my grandmother, Roseleen May. Rose and all her siblings, bar one, my Great Uncle Walter Eatts, have now passed away.

Mabel was born in 1907, on Jaru Country in a women’s birthing place at Lugangarna/Palm Springs, 40km east from Halls Creek in the east Kimberley.

Mabel’s mother, Nellie, was a strong woman who ensured her baby was born into love and sung to by the women of her Country.

Upon her birth, Mabel’s delicate body was waved through the smoke of a burning campfire and was embraced by Country herself, by her kin, and by the ancestors from whom she descended.

I have a formidable tribal ancestry that goes back for millennia. My great grandmother’s ceremony of birth runs through me.

Read more: Why is it legal to tell lies during the Voice referendum campaign?

At the time of my great grandmother’s birth, Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia were frontier war zones. From the 1880s, Mabel’s family witnessed the arrival of thousands of predominantly male, non-Indigenous gold prospectors and pastoralists to the Halls Creek region.

Their arrival bought with it a culture of legislated and unlegislated violence, oppression, and exploitation of Aboriginal people.

There are more than 32 verified massacre sites in the Kimberley region, dating from 1829 to 1926. Aboriginal women and their children were abducted and given to landowners and colonists who were accountable to no-one.

The Western Australian Aborigines Protection Act, 1886, officially introduced to “protect” Aboriginal families, did little more than support pastoralist demands for free Aboriginal labour, and legislate their enslavement.

On 23 December, 1905, two years before my great grandmother was born, the Aborigines Act, 1905 was endorsed by the Western Australia parliament. It would be in place for 60 years.

Section 8 gave a state-appointed “Chief Protector of Aborigines” legal guardianship of every Aboriginal and “half-caste” child until they reached the age of 16.

Section 12 gave the minister authority to remove any Aboriginal person from one area or district and relocate them to another. It was an offence for any Aboriginal person to refuse to be removed.

In 1909, Kimberley Police were instructed to identify all “half-caste” children and make arrangements for their removal. Travelling Police Inspector James Isdell wrote:

“I was glad to receive [Chief Protector Gale’s] telegraphic instructions at Halls Creek to arrange for the transport of all half-castes to Beagle Bay Mission, it should have been done years ago.”

In 1911, at the age of five, Mabel arrived as an inmate at the Beagle Bay Mission. She never saw her mother again.

Mabel lived there for 15 years. In 1926, aged 20, she was sent to work as a domestic servant for the Everetts, a prominent pearling family in Broome.

In 1928, Mabel gave birth to my grandmother, Rose. Rose’s father was George Joseph Francis, a Yawuru man who was well-respected by business owners in Broome, working in the region as a painter, sailmaker and abattoir labourer.

Under the Aborigines Act, 1905, all marriages of “half-caste” women in the state were authorised by the Chief Protector. George applied to the Protector to marry Mabel; however, Mabel rejected his offer.

We’ll never know why. However, under the Act, Mabel was not the legal guardian of Rose, and if Mabel married an Aboriginal man, this would continue to be the case.

Read more: Voice to Parliament: Debunking 10 myths and misconceptions

In 1930, Mabel married Jack Albert Eatts, a drover and station hand who identified to police as white. Through marriage to a “white” man, Mabel achieved some degree of exemption from the 1905 Act.

Exemption, however, wasn’t all it claimed to be. Mabel’s children could still be removed. Exemptees were subject to police surveillance, and exemption status could be revoked at any time.

Exemptees were required to “cease to be Aboriginal” – associations with Aboriginal extended family and communities were forbidden, as were cultural practices and the speaking of languages.

The 1905 Act was amended in 1936, giving the Aborigines Department increased powers to remove Aboriginal children from their mothers. So, in 1939, Mabel and husband Jack got hold of a Ford truck, loaded their belongings and their five children, and fled the Kimberley region, never to return.

This is just a snapshot of Mabel’s life. She was an extraordinary woman who navigated oppressive policies her whole life.

Mabel didn’t have a public voice. However, through our family’s storytelling, she now does.

A Voice matters

In 2015, the Referendum Council was appointed by then PM Malcolm Turnbull to advise on progress towards a referendum to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Constitution.

This council held 13 First Nations Regional Dialogues to discuss this in six months, between December 2016 and May 2017. The delegates drafted and overwhelmingly endorsed the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and issued it to the Australian people.

They called for a constitutionally entrenched First Nations Voice to Parliament, and a Makarrata commission to oversee a process of treaty-making and truth-telling.

With unseemly haste, the Turnbull government rejected these calls. The referendum towards the Voice to Parliament is now going ahead, and must occur before 16 December.

This July, we celebrated the NAIDOC theme “For Our Elders”. I once heard that we must be in the room to change it. For our Elders, and for future generations, I will say this: Let’s ensure that the voices of Aboriginal families are recognised in our nation’s constitution.

Let’s ensure Aboriginal families are in the rooms where decisions are made that affect them.