When Kylea Tink, Member for North Sydney, decried the “unconstructive noise and aggression” in Australia’s Parliament this week, she wasn’t merely venting frustration. She was challenging the nation‘s political culture, a gesture that marks a turning point in the gender dynamics of Australian leadership.

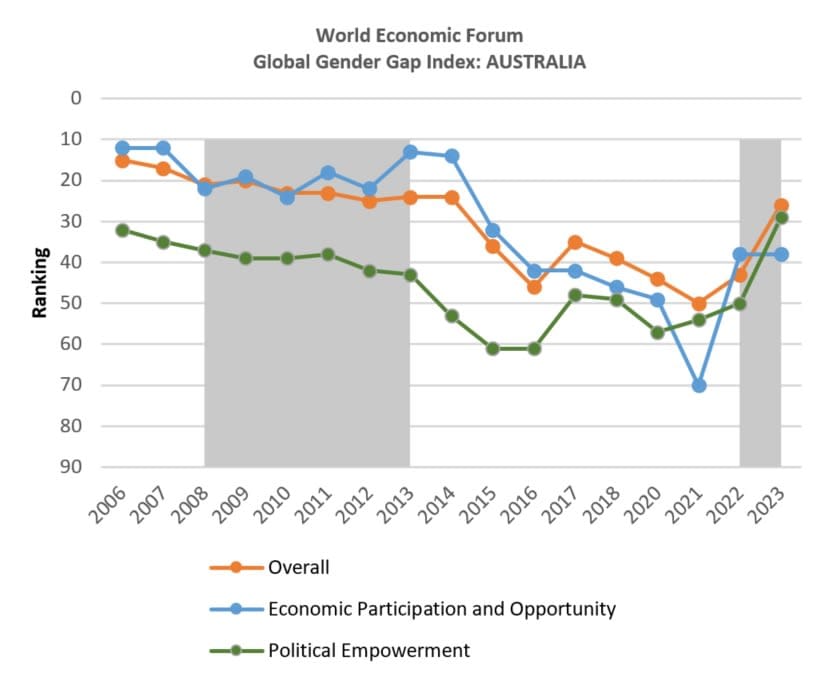

This significant moment dovetails with Australia’s impressive rise in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2023. The country catapulted from a mediocre 50th in 2021 to a commendable 26th rank recently. This leap is not accidental; it results from deliberate political action to empower women.

The Global Gender Gap Index annually benchmarks the state and evolution of gender parity across four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity; Political Empowerment; Educational Attainment, and Health and Survival). It’s the longest-standing index tracking the progress of numerous countries’ efforts towards closing these gaps over time since its inception in 2006.

Further progress has been made in Economic Participation and Opportunity. Australia’s rank has climbed from 70th in 2021 to 42nd. While this is a laudable achievement, there’s still much work to be done.

As of 2023, our overall global ranking stands at 26, which has improved since last year, but is still behind New Zealand's fourth place, Rwanda’s 12th, and the UK’s 15th.

Monash University academics Professor Helena Teede and Associate Professor Joanne Enticott, from the Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation (MCHRI), have confirmed this upward trajectory.

Their analysis (See Figure 1) of a series of World Economic Forum reports reveals a clear link between political empowerment and improved gender equity ranking. They also show how quotas, affirmative action, and other targeted measures have dramatically increased the number of women in politics.

“The gender makeup in Parliament is not just symbolic, it’s instrumental to national progress,” says Professor Teede.

The overall rise in ranking in the Gender Equity Index is largely a result of the increase in the number of women in political leadership.

Overall, women make up 45% of federal parliamentarians. While Labor and the Greens lead with the highest representation (53%) of the political parties, independents have the highest representation of women (77%).

In stark contrast, the Liberal Party and the Nationals lag significantly behind (28%).

Meanwhile, smaller parties such as CA (Centre Alliance) and JLN (Jacqui Lambie Network) show 100% female representation, but their small size has less impact.

This illustrates that while Labor and the Greens are making significant strides as a consequence of equity policies, others without these policies have a long way to go, reflecting the broader cultural and institutional challenges that still need to be addressed.

Read more: Diversifying the gender equality lens to include migrant women

MCHRI academic and local government councillor Rhonda Garad emphasises the spillover effect of more women in political power.

“A critical mass of women in government can transform a culture, leading us from power displays to more respectful collaborative environments that benefit the nation,” she says.

All authors are at pains to point out that the imperative for change is not ideological, it’s empirical.

Take, for example, the recently-passed Workplace Gender Equality Amendment, aiming to close the gender pay gap. Starting in 2024, employers with more than 100 employees will have their gender pay gaps published.

A direct consequence of a more gender-balanced Parliament, this amendment is critical to addressing the current 13% national gender pay gap (compared to 15% in OECD countries).

The spillover of transformative leadership extends beyond politics, positively impacting the corporate, not-for-profit, and healthcare sectors.

Initiatives such as the $5 million National Advancing Women in Healthcare Leadership Program, spearheaded by Professor Teede, serve as prime examples of intentional structural reform. This program is designed to elevate women into healthcare leadership roles, with the specific aim of measurably improving outcomes for women.

The National Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s data corroborates that organisations with more women in leadership roles are more profitable and efficient.

And it’s not just about the economy. Associate Professor Enticott sums it up:

“This is not just a women’s issue, it's societal. It impacts the entire health of the nation, both economically and socially.”

The good news is that in 2023, the world has closed about 68% of its gender gap, improving slightly from last year. At this slow pace, though, it will take 131 years to reach equality between men and women.

While no country has fully closed its gender gap, Iceland leads the pack, and New Zealand in the Asia Pacific is doing very well (largely the legacy of Jacinda Ardern’s gender reforms). Different areas such as health and education are closer to equality, but politics and jobs still have a long way to go.

Australia has made some progress, but we’re still behind countries such as New Zealand and Rwanda. If we keep moving at this rate, it will take centuries to close the gaps in politics and the workforce.

So, when leaders such as Kylea Tink call for change, they join a collective effort to dismantle the outdated strongman politics that has long stalled Australia’s progress.

She contributes to a broader momentum for the intentional, strategic empowerment of women, an approach already yielding substantial gains in economic, corporate, and healthcare sectors.