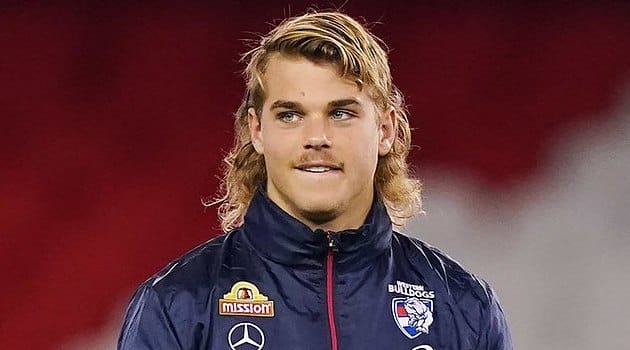

AFL star Bailey Smith’s “gotcha” moment, which led to a two-match ban, has reignited fierce debate over the effectiveness of the league’s illicit drugs policy.

During last year’s post-season, Smith was pictured with a small bag of white powder, with the image recently shared virally on social media. To his credit, the Western Bulldogs footballer confessed to his mistake and spoke candidly about his personal struggles.

#BREAKING Western Bulldog star Bailey Smith has been handed a two-match ban by the AFL after photographs and video emerged of him taking an illicit drug. #AFL #baileysmith https://t.co/24yfPbVPQt— The Age (@theage) June 16, 2022

Separated from his family and friends during the 2021 AFL finals’ hub and its aftermath, Smith found the pressure of being a high-profile footballer overwhelming. After the Bulldogs suffered a 74-point loss to Melbourne in the AFL grand final, Smith holidayed on the Gold Coast.

Hyped revellers at party hotspots proved a toxic environment for Smith, who confessed he was deeply ashamed of his indulgent behaviour. He said his mental health dramatically deteriorated after last year’s grand final.

The flashy midfielder took leave during the pre-season to improve his mental health, as he dealt with the effects of chronic anxiety.

Young – and often naive – footballers are targets in domestic and overseas nightclub culture, where recreational drugs and fancy drinks flow freely. It’s a trap for any person who’s vulnerable and falls into hard partying, often with nasty side-effects. We only need to look at the most recent Jordan De Goey indiscretion in a Bali nightclub for proof of this.

Jordan De Goey took aim at the media when his Bali antics hit the headlines but he only has himself to blame, says Mark Robinson. See all Robbo's likes and dislikes 👇https://t.co/z9XdqUqxcm— SuperFooty (AFL) (@superfooty) June 19, 2022

Smith attracts plenty of attention due to his flowing-blond-mullet hairstyle, brilliant blue eyes, and tanned, chiselled physique. He’s a picture of health – a perfectly-built athlete in the Adonis mould.

Known as “Bazlenka” on social media, Smith has a massive Instagram following of 374,000. He’s a marketer’s dream, and has lucrative endorsements with Cotton On, Monster Energy and McDonald’s. However, Smith’s rapid rise as a celebrity has come with new burdens and pressures outside the artificial football bubble – exacerbated in AFL-crazed Melbourne.

The post-season partying lifestyle, heightened after strict lockdowns and time away from the comfort of partners, family and friends, proved a temptation for the pin-up footballer. Alarmingly, someone always has a smartphone nearby.

Smith’s case has highlighted the need to review and change the contentious AFL three-strikes policy, and improve support mechanisms for highly anxious footballers. Smith received a strike, known as a notable adverse finding, under the policy.

The three-strikes policy is:

- The first positive test results in a suspended $5000 fine

- The second positive test results in a four-match ban and $5000 fine, and outed publicly

- The third positive test results in a 12-month suspension and a $10,000 fine.

Since the revised policy was introduced in 2015, not one player has been banned or outed publicly. Hawthorn’s Travis Tuck is the only player to receive three strikes, back in 2010.

Smith’s senior coach, the Bulldogs’ Luke Beveridge, says the illicit drugs policy should “disappear”, as many codes worldwide don’t have a policy for illicit drug use.

Beveridge says: “None of us really feel it works.” Players with mental health issues don’t get strikes, which Beveridge says is a “chink in the actual process”.

No easy fix

Media celebrity and former Collingwood president Eddie McGuire says footballers are open to blackmail if they’re caught using drugs and then the evidence is shared on social media. Smith’s photo could have been shared on social media during grand final week, and he consequently could have missed the most important match of the year.

“This is the big issue about illicit drugs, the opportunity for nefarious people to blackmail players,” McGuire said on Nine's Footy Classified.

“It's always been the big issue, going right back to the 2010s when Collingwood came out and talked about the volcanic situation. The drug rules were being absolutely laughed at by the players.

“The big issue – and the Australian Crime Commission were looking at this – was how players are going to get blackmailed into match-fixing because of their situation with illicit drugs.”

The reality is the AFL cannot possibly change its illicit drugs policy to create a perfect system. In the imperfect world of elite sport, with imperfect athletes that often strive for perfection, a one-size-fits-all policy simply doesn’t work.

The range of complex issues AFL footballers present means there’s no easy fix. The root of drug use is complicated, from “boys just being boys”, to forgetting the stresses of elite performance, or being influenced by alcohol, peer pressure, or feeling insecure.

However, footballers with addictive disorders, such as former AFL star Ben Cousins, suffer long-term effects and struggle to control their addictive urges.

Despite the policy’s flaws, medical experts proved in 2012 the harm minimisation strategy to reduce illicit drug use was working. Well-known sports medicine doctors Peter Harcourt, Harry Unglik and Jill Cook published an article in the British Medical Journal of Sports Medicine, outlining a testing strategy that highlighted a significant reduction in drug use. The doctors claimed player education, more testing both in and out of competition, and the policy’s harm minimisation attributed to less drug use among elite footballers.

Drug testing needs to occur in the off-season, so AFL players aren’t tempted to use recreational drugs, and fall into bad habits that could lead to addiction.

There are always pitfalls in seasonal drug use, and the illicit drugs policy would be more effective if testing was enforced consistently – all year round. Hair testing can detect drug use dating back three months, and this is recognised as a deterrent that would aim to reduce recreational drug use post-season.

AFL needs a working group

The AFL needs to assemble a working group to revise the illicit drug policy, which may include a behavioural disorders expert, sports medicine specialists, AFL coaches and doctors, an AFL Players Association representative, a psychologist or wellbeing specialist, a cybercrime specialist, and key AFL managers.

It will need accurate feedback from AFL players and key club personnel, plus confidential and statistical medical evidence of drug use. A collaborative effort will enhance the knowledge to identify the drug policy’s pitfalls and strengths in a bid to improve its effectiveness. Good collaborative research will help take the policy forward and improve its purpose.

Ultimately, the policy is designed to protect the wellbeing of players, and this goal must be of critical importance as the AFL finds better solutions.