In troubled times, people look for strong leaders – men and women who offer decisive action to address collective problems, and promise the capacity to deliver. They initially present as larger-than-life characters, and we’ve had our share of them: Robert Menzies, Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating, and perhaps Kevin Rudd.

The dual problems of the pandemic (with its tail of economic problems) and the destabilisation of the international order, with the rise of an assertive China and the outbreak of war in Europe, has provoked a crisis mentality in which the demand for such leadership is intensified.

Read more: How changing times made Australia's political leaders more disposable

But when one ponders the daily newsfeed of the election campaign and the record of the past three years, the results are dispiriting.

Each of the major parties is spraying cash at carefully targeted demographic sectors and seats. Neither is showing leadership in addressing the budget problems that portend a horror budget after the election.

The one-man band that was Scott Morrison in the 2019 campaign has failed to deliver, and he’s trying to run the same campaign in different circumstances. The cautious superintendence of a small-palette agenda by Anthony Albanese has led many to castigate its lack of ambition.

The major parties are in decline, and neither appears capable of delivering the big ideas needed for current challenges.

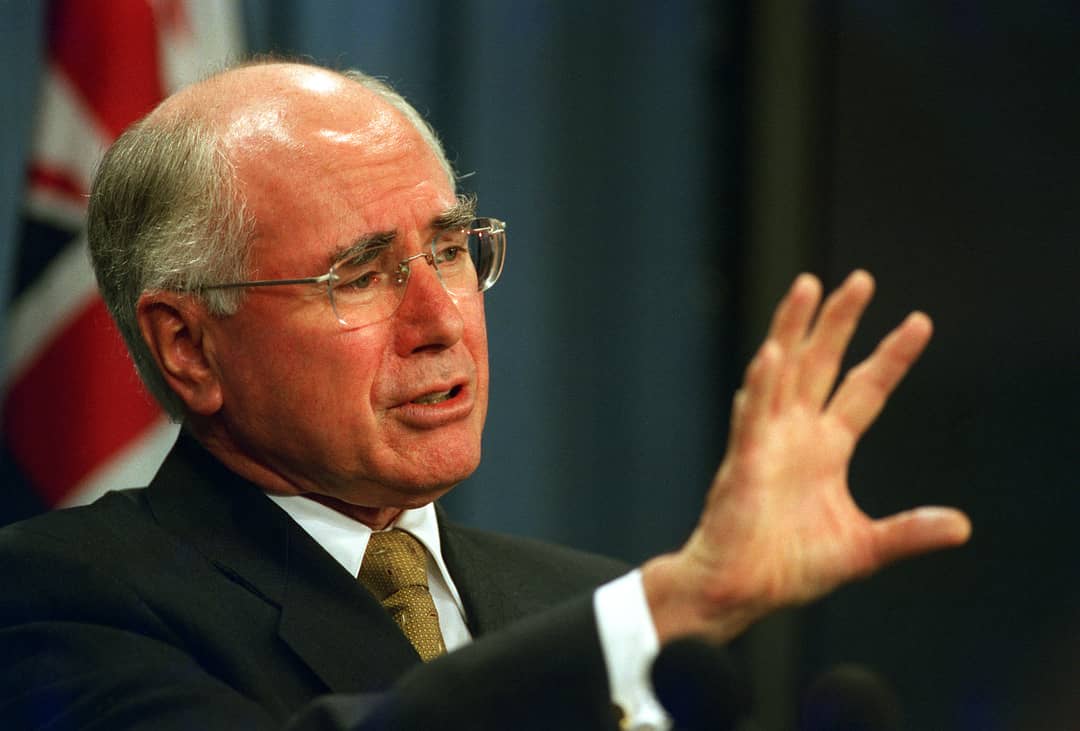

Consider Morrison’s claim to the mantle of strong leadership. If one rates him against John Howard (above) – not a larger-than-life character, but certainly a strong leader – Morrison fails to measure up. Howard had a rocky first term, but demonstrated the courage of his convictions early with gun law reform, despite opposition from the National Party and many in rural constituencies.

He ran a disciplined cabinet, and persisted with the economic reforms introduced by Labor, but adapted them to his own purposes, building a coherent policy program.

He made the brave decision to introduce a goods and services tax (GST), and never introduced a new policy measure without showing how it aligned with specific liberal values, rather than waffling about “Australian” values.

He carried his party with him, regularly visiting party branches to talk with and listen to members. He could rightfully claim that whether people agreed or disagreed with him, they knew who he was and what he was about. The result? Eventually he “owned” the party.

Now Morrison, too, has had a difficult first term, with challenges not of his making. But there’s been no courageous decision, and certainly not the will to challenge the way in which he’s been held hostage by the National Party and its costly demands.

Morrison has been reactive rather than proactive – rarely thinking long-term, but preoccupied with the immediate. He’s failed to see crises coming, or imagine what his role in addressing them should be.

The overwhelming impression is that there’s nothing of substance behind the “ScoMo” persona. And it’s a canker that has spread throughout the government, as the paucity of policies now on offer demonstrates.

Read more: Leaders only inspire when we feel part of their group

What, then, of the Labor Party? Anthony Albanese isn’t a big personality, like Hawke or Keating, nor an adept media operator like Rudd or Morrison. He’s not a dominating figure on the campaign trail, although he managed to outfox Morrison in both leaders’ debates so far.

In having been careful not to present a big target, open to the demolition Morrison visited upon Shorten, he has disappointed the Labor faithful.

To take one instance, the party has had three years to address a factor thought to be integral to Labor’s loss in 2019 – its disregard of the impact of its climate transition policies on the communities most affected.

Its failure since to prosecute the case for the transition to renewables as presenting opportunities and growth is inexcusable. It’s now done so in a detailed and costed policy proposal, but too late – those frontline communities think neither party has done enough to explain any advantage that will offset the disappearance of jobs so long central to their economies.

Maybe the same might be said of the Labor policies now presented. They’re modest, and beg questions about how they might be afforded. But they promise to take action on and responsibility for real problems in health, aged care, the energy transition and jobs, gender pay equity, manufacturing, and housing affordability.

Unlike the Coalition’s policy program, Labor’s relies on substantiating research, and represents a start that might in the right circumstances be built upon. Still, Albanese and his team will have their work cut out to convey these messages when few are paying attention.

Perhaps we need finally to be looking for different leadership capacities. Julia Gillard, after all, did not present as a strong leader in 2010 relative to Rudd in 2007.

Yet, despite having to negotiate in a minority government, being belittled and demeaned by Tony Abbott and his colleagues, incrementally undermined by some within her own ranks, and continually under assault in some media quarters, she was the closer on much that Rudd left unfinished, achieved the only workable emissions-reduction scheme we’ve had to date, and passed more legislation than any other administration, not all of which the Coalition has subsequently been able to reverse.

Read more: Australians to our leaders: ‘Lift your game and think long term’

At Albanese’s campaign launch, journalist Katherine Murphy noted he was modelling a different style of leadership:

“He’s not a powerful orator […] He didn’t seek to dominate the room: he sought connections in it, looking for faces, connections, cues[…] [without] the hallmarks of toxic masculinity. Rather than a set jaw, there’s an incline of the head, a gesture of listening – a physical glance at humility.”

This brings to mind John Bew’s marvellous biography of Clement Attlee.

In the 1945 British election, the Tories, and some in his own Labour Party ranks, assumed that Attlee – a diminutive, unassuming man they called “a sheep in sheep’s clothing” – would be overpowered by the venerated war leader Winston Churchill. Yet Attlee prevailed, and then presided over a transformation of British society that has led to Bew arguing persuasively that he was Britain’s greatest peacetime prime minister.

Might Albanese be Australia’s own Attlee?

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.