The images and stories projected across our media over the past two weeks are alarming. Some seem unprecedented.

- Young women apparently using their feminine powers of attraction through TikTok to lure and capture Russian soldiers

- Women and girls ripping up scraps of material and tying wire nets to protect Ukrainian soldiers from drone missiles – a low-tech response to the brutality of unprovoked, high-tech warfare

- Female politicians and beauty queens voluntarily taking up arms without conscription in the streets of Kyiv, Kharkiv and other cities and towns.

Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Education, Inna Sovsun, has also been using her communicative power to spread information to the world about what is happening, posting an image on Twitter with a Kalashnikov rifle at her side.

My dad is signing up for a territorial defence squad. My boyfriend is with the Army. I'm working as hard as I can to give information to the world about what is happening here.

But if need be – I'm ready to fight🇺🇦 pic.twitter.com/8OlWOyvlnE— Inna Sovsun (@InnaSovsun) February 26, 2022

Other images of the Ukraine conflict are familiar.

Women directly confronting Russian soldiers on the streets recall similar scenes from 1968 Prague during the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia.

As one Ukrainian Australian reports, there was a sign on the bus stop that read: “Bitches, f--- off out of my village and Ukraine, Baba [Grandma] Nadia.”

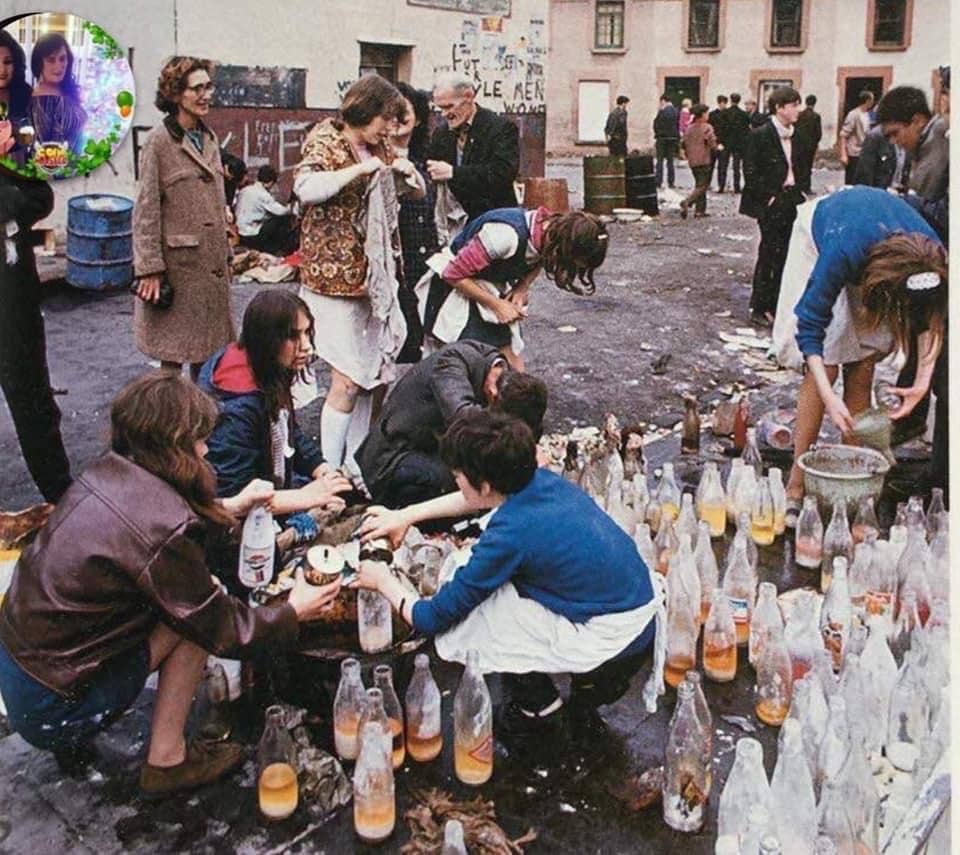

One particular image struck us, of women in Dnipro making Molotov cocktails to defend their city from Russian attacks.

It’s remarkably similar to another photograph taken in August 1969, in Derry, Northern Ireland, of women from the Catholic Bogside area making petrol bombs for use in clashes with the Royal Ulster Constabulary and loyalists who were attacking their homes.

The glimpse into the everyday realities of war reveals parallels with previous conflicts, including the conflict in Northern Ireland.

The media clips highlight women’s fighting roles alongside men’s on both the front lines and the kitchen tables of struggles for independence.

Women are not being quietened, nor are they silent victims in war. Women, particularly those who don’t have the primary responsibility for children, frequently take the fight for the group cause into their own hands.

What’s different now in Ukraine is perhaps only the widespread coverage of these so-called “backroom” defence roles.

The role of women in Northern Ireland's fight for independence

By contrast, these roles were less visible in Ireland, despite a long tradition of women’s involvement in their centuries-long struggle for independence.

In Carol Coulter’s 1993 book, The Hidden Tradition, she explains that in the 1860s, women smuggled revolutionary literature and arms into Ireland.

Feminist historian Margaret Ward further examined the tradition of women’s involvement in Irish nationalism in her 1989 book, Unmanageable Revolutionaries.

She reveals that in the years preceding the Easter rising of 1916, women raised funds for the purchase of arms and became skilled in first aid. During this time they even began to organise themselves into quasi-military structures, with some taking up rifle practice.

In 1921, the controversial Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed, granting independence to only 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties. Sinn Fein was split on the issue, but interestingly the women did not split – all six women who held seats for Sinn Fein in the Dáil (Irish parliament) rejected the treaty. They were far less inclined to compromise on their ultimate objective of an independent socialist republic for Ireland in its entirety. In taking this stance, they committed themselves to continue the fight.

Read more: How women can help prevent terrorism

In the more recent iteration of conflict in Ireland (1969-1998), women continued to play a pivotal role in the Provisional IRA’s campaign – hiding and transporting weapons, operating safe houses, assisting volunteers across the border, gathering intelligence, smuggling messages and contraband into and out of prisons and, in some instances, taking up arms themselves.

The assumption is often that women participated in these activities under duress, but in recent interviews gathered as part of Gabrielle Williams’ doctoral research, many women talk of empowerment, adventure and personal commitment to the cause.

They contrast the drudgery of women’s domestic lives with the excitement of being a critical part of something bigger, something important. There’s a tendency in analysis of conflicts to downplay the political agency of women, to define their participation by reference to their relationship to men. This contributes to the invisibility of women’s roles.

This isn’t to say that all women are empowered by conflict. Clearly this is not the case.

We know women and girls are disproportionately affected by displacement in war.

The fighting in Ukraine has already forced many civilians to flee their homes, and if the conflict continues, thousands of additional families will be forcibly displaced, dramatically escalating the scale of the already dire humanitarian situation, and increasing the risk of sexual violence and exploitation.

The risks have not gone unnoticed, with the UN Under-Secretary-General and Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict expressing deep concern about the deteriorating situation in Ukraine.

She’s called for the urgent protection of civilians, especially women and girls who are at heightened risk of violence.

And despite the invocation of the sanctity of mothers and motherhood in almost all wars, it’s mothers and babies who often suffer the most.

Donate money to save pregnant women and newborns in Ukraine!

The war has created a terrible and dangerous situation for pregnant women and newborns.

They need medicine, hygiene articles and other supplies to increase their chances of survival.

Please read the thread and share! pic.twitter.com/RCCHoLUQAw— Anders Östlund (@andersostlund) March 6, 2022

In Ukraine, we’ve heard about babies being born in bomb shelters. In all wars women continue to fall pregnant and give birth, but often in circumstances that guarantee their healthcare needs will not be met, leading to death and disability. As for reproductive health more generally, it’s rarely prioritised in an emergency, nor funded as it should be.

There are myriad other roles women play in conflict – from shouldering the burden of household finances, to bearing the weight of grief, and intergenerational social and emotional recovery.

Whether it be the women in the Bogside in 1969, or the women in Ukraine performing the very same tasks more than 50 years later, the parallels serve as a reminder that no war is ever only a men’s war.