Note: Since the publication of this article, Russia has launched its invasion of Ukraine. Monash offers our support to members of our community affected by the current conflict. Find out more.

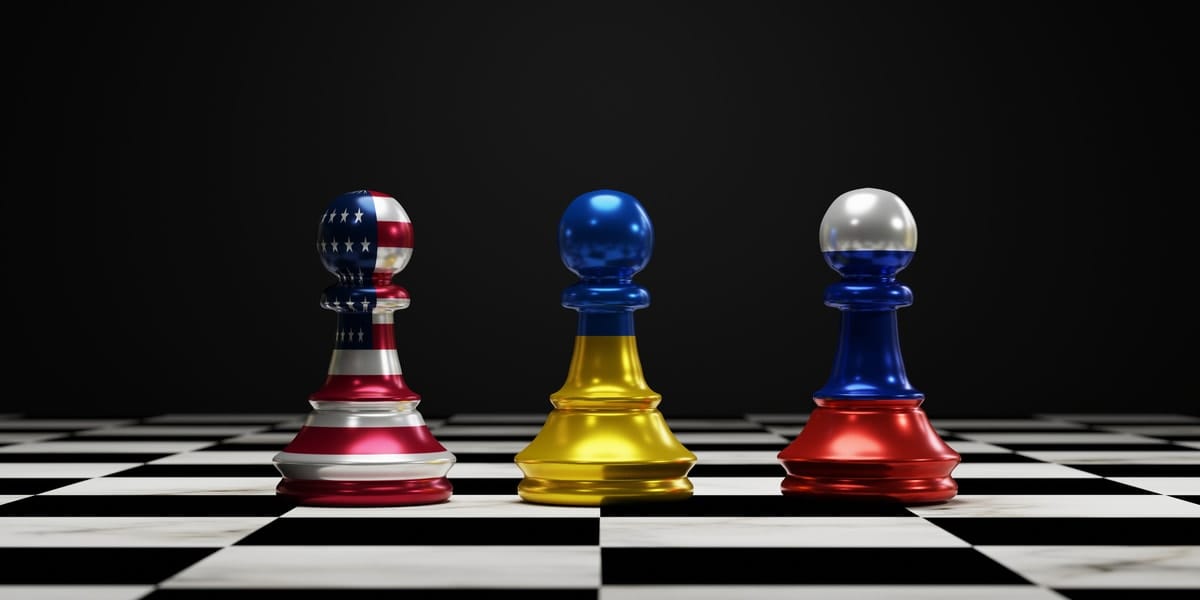

Speculation is rife about whether or not Russia will further invade Ukraine. Will the most dangerous geopolitical crisis in Europe since the dark days of the Cold War spill over into war?

The United States, its NATO partners and Ukraine have been in dialogue with Russia for weeks seeking a resolution. As yet, no real progress has been made.

Congruent with similar crises during the Cold War, the current standoff has a dangerous nuclear weapons backdrop. It’s been some 40 years since the United States, NATO and the Soviet Union were embroiled in such a quagmire.

Today, Russia is trying to impose its own constraints on American and NATO policy in Europe, and it does not come as a total surprise.

Why this crisis, and why now?

President Vladimir Putin has long had the view that Russia should have buffer states between it and the NATO countries of Europe. Ukraine’s geography is crucial to Russia’s strategic policy objectives. With Belarus to its immediate north, Ukraine is the only other remaining buffer state protecting Russia from NATO pushing against its western flank.

For several years, Ukraine has been drawing closer to the West, especially in economic and strategic terms. This situation is now unacceptable to Moscow. It’s in Russia’s interest that Ukraine remains a vassal to Moscow. Putin is now positioning Moscow to have a much greater influence on European strategic affairs by redressing the balance of power.

In December, Russia released two significant draft agreements aimed at subverting NATO and US policy. There are several key points Russia wants addressed. It wants an assurance, in writing, that Ukraine never be allowed to join NATO. Additionally, it wants all NATO forces pushed back to pre-1997 positions.

Further, Russia insists the United States be prohibited from deploying intermediate-range missiles in Europe. This has echoes of the final decade of the Cold War that resulted in the INF Treaty of 1987. Signed by Reagan and Gorbachev, it was a regime Russia effectively violated and ended in 2017 with the deployment of its own intermediate-range missiles.

Thus, the present crisis in Eastern Europe has its origins in the Cold War.

Echoes of history

Putin has made no secret of his nostalgia for the Cold War era, when the Soviet Union was a superpower. In 2005, he lamented that the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century was the demise of the Soviet state.

Since that time, he’s made calculated moves to restore Russian power and increase its sphere of influence.

In 2008, Russia went to war with Georgia over South Ossetia and Abkhazia. It effectively now controls both territories. NATO expansion, and talks suggesting Georgia would soon join, was the critical factor in Moscow’s decision to act.

In 2014, Moscow followed with the annexation of Crimea in southern Ukraine and the incursion into eastern Ukraine, where it seized, and remains in control of, the Donbas region.

It’s also important to note that this trend of applying Russian military might continued with Moscow’s involvement in the recent Syrian war. It presented the perfect opportunity for Russia to re-enter the Middle East.

In each case, Russia acted swiftly, demonstrating a rational, zero-sum approach to any international security issue it perceived to be a threat to its sovereignty, or presented an opportunity to tilt the balance of power in its favour.

It should therefore come as no surprise that Putin has taken the geopolitical temperature and is once again rolling the dice in Eastern Europe. A wily strategist, he’s again testing the credibility of the US and NATO, and their will to deter and check any potential moves Russia might make.

Read more: How to make an invasion of Ukraine an unattractive proposition

Putin’s actions have exposed the divergence in thought among leading European Union and NATO states about how to handle strategic threats. France wants to adopt a more strident posture, with the EU having its own strategic forces. Germany, the other leading EU power now with a new government, takes a more considered approach bound in its own history and its dependence on Russia for energy.

Despite these differences, President Biden is making a determined attempt to lead and present a united effort by the West to resist Russian pressure.

In seeking to annex more of Ukraine, Russia is attempting to rewrite history and further recalibrate the international order. On the global geostrategic level, its actions may well embolden other revisionist powers with territorial ambitions to act similarly.

This is why the US, NATO and its allies cannot afford to back down to Russia’s demands. The stakes are very high on both sides of the equation. Presently, all parties are locked in a stalemate, much as they were during the decades of the Cold War.

And just like the Cold War, only far better-understood by the general public at the time, nuclear weapons continue to hang over every strategic gambit played out between Moscow and Washington.

Nuclear sword of Damocles

In much of the analysis of this issue, little attention has been paid to nuclear weapons. The fact remains that, decades after the Cold War, strategic competition between Washington and Moscow always plays out with a nuclear backdrop. The game of brinkmanship being played by Putin has something of a familiar ring to it.

Let’s not forget that Washington and Moscow have in the past had crises escalate to the point where the prospects for the exchange of nuclear weapons were dangerously high.

The 1962 Cuban missile crisis was such a time.

Similarly, but less well-known, in 1983 the training exercise Operation Able Archer was viewed by the Soviets as a nuclear attack against them by the West. By good fortune, the world narrowly avoided a nuclear calamity.

This happened at the height of tensions over strategic missile deployments in Europe. It’s not beyond the realms of possibility that a similar misreading in a deteriorating strategic environment between Washington and Moscow could again occur.

Recent studies estimate the US has some 5500 nuclear warheads, and Russia about 6255. Significantly, approximately 2000 remain ready for rapid operational deployment between them. Although the world breathed a sigh of relief at the end of the Cold War in 1991, the nuclear weapons menace didn’t go away. It was merely pushed aside.

Without knowing how a conflict might escalate once it starts, Moscow and Washington policymakers will be very much alive to the fact that any war involving Russia and NATO over Ukraine must be avoided at all costs.

Read more: Ukraine v Russia: what next after the Kerch Strait aggression?

And yet, there’s another nuclear dimension in play. Will this crisis dent existing – and imperil future – nuclear arms control and verification processes between Russia and the US? It’s too early to tell, but a continuing downward spiral and invasion by Russia could have very serious consequences for moves to reduce strategic nuclear stockpiles.

As nuclear weapons states around the world continue to modernise and improve delivery systems and weapons platforms, there’ll be no incentive for them to slow their own efforts to enhance their nuclear capabilities. The crisis over Ukraine may yet prove an incentive for speeding them up.

The gravity of the present standoff between Russia and the United States and NATO mustn’t be underestimated. It presents a very real danger of escalation to a nightmarish proportion.

This may seem dramatic on the surface. However, practitioners in the field of nuclear weapons policy are only too aware of how quickly a conflict involving Russia and the West may escalate to the nuclear level.

Will Russia be deterred?

Putin has continued his attempts to sow division and stir trouble with, and between, the US, the EU and NATO. He’s done so since 2008. At the time of writing, the presence of a sizable Russian military deployment in the vicinity of Ukraine has created chaos, uncertainty, and a major geopolitical challenge for the West.

To that end, Putin may have already achieved his objective. However, he approaches international relations as a zero-sum power game. He rolled the dice and won in 2008 and 2014. But has he miscalculated the odds in 2022? Almost all of Russia’s demands will be unpalatable to Washington and its allies. This makes finding a solution to the crisis all the more challenging.

If Putin demobilises his military and retreats, there’s every chance he’ll seek to make his cherished strategic gains elsewhere in the future.

Yet, retreat doesn’t reconcile with his hard-man image. He remains determined to prove, as he did in 2008 and 2014, that the US and NATO are toothless tigers on Russia’s periphery. A strategic win for Moscow in the current standoff will be noted by other revisionist powers, and further undermine the existing international order.

The United States and its European allies must present a united front. They must make crystal-clear to Putin that any further moves against Ukraine will be checked with a response that will be crippling for Russia.

Russia must be faced with a price that is too high to pay. This is the essence of deterrence. Fraught though it was at the time, deterrence helped keep the peace in Europe during the 45 years of the Cold War. It must do the same again in 2022.