In October 2022, it will be 60 years since the Beatles released the single Love Me Do.

Anticipation of this anniversary prompts consideration of the continued interest in the band, as wherever in the world one happens to be, evidence of its legacy and impact can be inescapable, and sometimes comes as a delightful surprise.

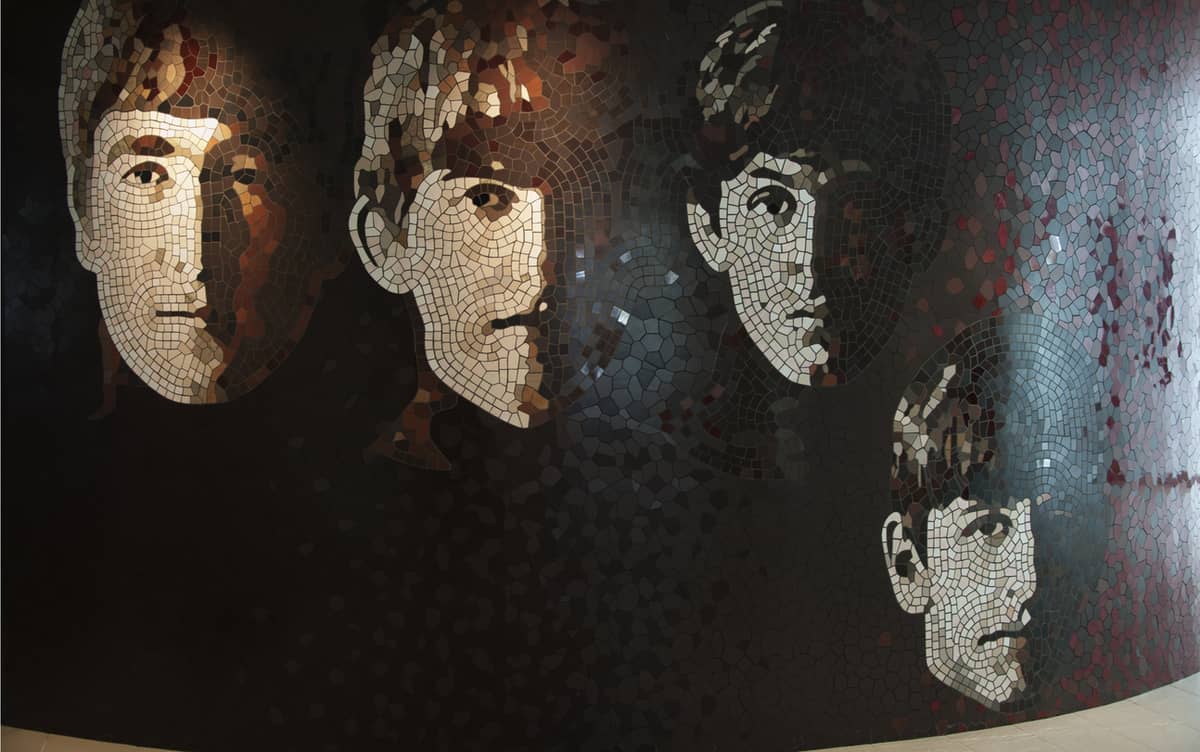

This was the case on a recent bike ride (within lockdown limits, naturally), when my wife pointed out a mural dedicated to the Beatles.

Set back on an unprepossessing St Kilda alleyway, its colourful images drawn from the 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine, the mural references a song from the Sgt. Pepper’s album, announcing: “I get by with a little help from my friends.”

Read more: Japan '66: The Beatles, Budokan ... and death threats

Not far from this vernacular art site, in December (infection rates willing), the Palais Theatre will host Come Together, when a 24-piece symphony orchestra conducted by George Ellis will offer two hours of Beatles songs with vocals from the Church’s Steve Kilbey, Rick Price, Bobby Fox, and Dave Wilkins.

By this point we’ll also have had the opportunity to view Peter Jackson’s Get Back, a revision of the 1970 documentary Let It Be. To be screened by Disney in November, the size and scope of the project is signalled by an emphasis on Jackson’s three years of labour and access to 60 hours of archive footage, which has not been seen for a half-century.

The apparent appetite for material about the band is measured in the resulting series of films that reworks Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s lean 80 minutes into six hours of documentary to be revealed over three days in what promises to be a global televisual event.

Of course, all of this is anchored in the music, with the series following the release of a multi-volume version of the album Let it Be, collating rehearsals, outtakes and new mixes of the original set of tunes.

Jackson avers that his series is no nostalgia exercise, but a new contribution to a necessary understanding of the band:

“It’s raw, honest, and human. Over six hours, you’ll get to know the Beatles with an intimacy that you never thought possible.”

Alongside such officially sanctioned exercises, an efflorescence of other activities that express similar objectives and a fascination with every aspect and minutiae of the group’s activities continue to appear and appeal.

These include films concerning a visit to Rishikesh – Meeting the Beatles in India (2020, directed by Paul Saltzman) and The Beatles and India, (2021, directed by Ajoy Bose and Pete Compton) – as well as exhibitions and heritage events, podcasts, musical performances, memoirs and popular studies.

Creative speculations such as Danny Boyle’s 2019 film Yesterday imagine a world in which the band never existed, or conversely, as in Daniel Rachel’s new book, Like Some Forgotten Dream (2021), ask: “What if the Beatles hadn't split up?”

Auditing and adding to this field of activity is a wealth of scholarly research devoted to John, Paul, George and Ringo, the meanings of the band and its music, spanning disciplines and methodological approaches.

This industrious field of production – of creative practice, thought and, indeed, pleasure – confirms the place of The Journal of Beatle Studies, which has just been announced by Liverpool University Press, and of which I am co-editor with Holly Tessler of the University of Liverpool.

In establishing this peer-reviewed journal, our aim is to navigate and map the meanings of the Beatles, the prodigious attention they’ve attracted, and the manner in which they’ve been investigated and narrated.

In turn, the Beatles offer a lens through which we might explore wider issues and the purposes to which they’ve been enlisted.

Popular music as a historical resource

Certainly, the Beatles have been a feature of my research into the ways in which popular music offers a historical resource, and has come to be validated as heritage and as object of cultural policy.

This is witnessed in processes of popular music’s preservation, when it was once deemed disposable, in its performativity in public cultural institutions, and how it’s deployed as a promotional feature in place branding and in support of the contemporary creative industries.

Regarding the Beatles, for instance, I’m reflexive about how this last function is apparent in the existence of the journal itself. After all, Tessler is also director of a master’s program, The Beatles: Music Industry and Heritage, launching this month.

This punctuates the sense of cultural value of the band for her institution and the City of Liverpool itself, which capitalises on the pilgrimages of fans through tours, museums, events and assets – tangible and intangible – celebrated in Beatles mythology.

In light of the place of the Beatles in cultural memory across the globe, it’s worth noting that their continued status, the attention to them as heritage objects or subjects of academic study, has never been guaranteed, nor is it necessarily secure.

The City of Liverpool was famously slow to recognise its assets, even when the Beatles had long departed. This status and attention is the result of a process of continued production and negotiation, of competing interests and disputes over the band’s meaning and legacy – something the new journal seeks to understand.

Caution along with respect

The message of the St Kilda mural reminds one of the benign affectiveness of most of the band’s output (there’s more troubling material there, too), which to a degree is reflected in the attitudes of the most vociferous of fans (and even scholars).

As with any cultural object, however, one finds those same fans express a sense of ownership of the band and its meanings. This can translate into a possessiveness that can prove hostile to enterprises like our own, and indeed the establishment of Liverpool’s master’s program elicited a range of inchoate negative reactions alongside enthusiasm for this mode of canonisation.

Just like the mutual scholarly scrutiny that ensures the quality of our work, then, the public nature of dealing with the Beatles merits caution as well as a respectful critical eye.

Our first step in invitations for contributions to the inaugural edition of the journal will be to survey new agendas and directions for study in mapping this field.

As the industry devoted to the Beatles continues to nurture creative responses, new generations of devoted listeners and scholarly scrutiny, this will support the mission of The Journal of Beatles Studies.

Perhaps it’s not too soon, then, to begin anticipating the centenary of that first single, and what the Beatles will mean at that future point.