Over the past week, media attention worldwide has been focused on singer Britney Spears’ attempts to free herself from the conservatorship that limits her financial, professional and personal autonomy.

The idea that an internationally successful pop superstar “isn’t even allowed to choose the colour of her kitchen cabinets”, let alone maintain control over her medical and reproductive decisions, has proven deeply unsettling.

There’s been justifiable outrage over the past week at Spears’ treatment, and yet the singer has lived with the conservatorship since 2008, and the #FreeBritney campaign has been striving to draw attention to her plight for more than a decade. A recent New York Times documentary, Framing Britney Spears, brought a new audience to the case.

However, the factor that has really turned the tide in Spears’ favour is that we’ve been able to hear her own voice on the matter.

Performers forcibly committed

Over the past century, many successful female performers have been forcibly committed to psychiatric treatment, frequently by members of their family, and compelled to remain in care for years, if not decades.

Some, such as Lily Elsie and Audrey Munson, never performed again; however, others, notably child stars Judy Garland and Patty Duke, were able to keep generating profits through managerial manipulation and drug regimes.

Actress Frances Farmer was put on a conservatorship following episodes of public drunkenness in the 1940s, and endured years of institutionalisation in a psychiatric hospital. In 1950, she was released into her parents’ care after her father told the courts her help was needed at home, but it was another three years before the actress could petition the Supreme Court for the full restitution of her civil rights and resume her career on her own terms.

Studios and agencies worked tirelessly to keep evidence of a star’s illness away from the public eye, but occasionally it slipped through.

In 1953, Vivien Leigh fell ill while filming Elephant Walk, and was pictured comatose on a stretcher being flown back to London from Los Angeles – images that were swiftly wired around the world.

On arrival at Heathrow, Leigh had to counteract the image, allowing herself to be photographed descending from the plane, smiling and elegantly dressed, while her husband Laurence Olivier promoted a narrative of “nervous exhaustion”. The tarmac performance, and the esteem with which “the Oliviers” were held, meant Leigh’s chronic mental illness remained largely secret.

Mental illness the defining feature

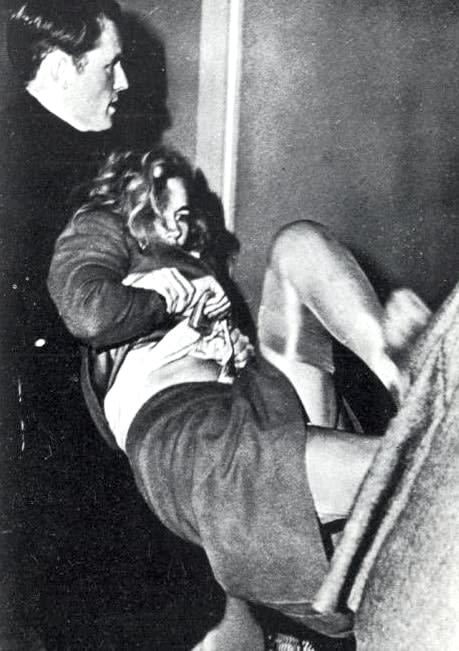

At other times, images of the female performer in distress – of Frances Farmer being dragged kicking and screaming into court, or Gail Russell looking dazed and confused as she’s handcuffed after crashing her car – are so powerful, they consume everything the performer has done previously and will do in the future.

Mental illness becomes the defining feature of their celebrity and performance identities; the notion of living and working well with (let alone recovering from) mental illness, is rarely entertained.

One of the key points to emerge from the most recent Spears’ proceedings, is that the conservatorship requires her to attend weekly therapy sessions in a public location, rendering her peculiarly exposed to the paparazzi. It’s difficult to view this as other than an attempt to maintain the narrative of Spears as a woman who is “still unwell”, supporting the argument that underpins the conservatorship.

A notable exception

In recent days, numerous media commentators and Twitter users have drawn parallels between Spears and Judy Garland, or Spears and Frances Farmer, among other examples. Such comparisons draw our attention to the way Spears exists on a continuum of responses to female performers who’ve had experiences of mental illness.

What’s notable about the Britney Spears case, however, is that it’s a rare instance of a performer in these circumstances having her voice heard.

While aspects of Garland’s mental illness were publicly acknowledged, they were often framed as overwork and heightened emotional sensitivity – the same sensitivity that so thrilled her fans. The familial and managerial issues that influenced the development and trajectory of her illness and its treatment were only hinted at in her lifetime.

So often, what we can “see” becomes the story, making access to the voice powerful and important, yet this is something women in Spears’ position have rarely been afforded.

Farmer’s voice is even more elusive. Her 1958 appearance on This Is Your Life forces her to listen to a second-hand version of her life story, to which she’s only allowed to make occasional interjections. And the deeply unreliable “memoir”, Will There Really be a Morning?, wasn’t published until two years after her death, its narrative arranged by an external hand.

There’s an urgency and insistence in Spears’ testimony that forces us not only to listen, but to take a position. By being given a platform for her voice, Spears invites us to consider the broader institutional forces that accompany and compound mental illness.

So often, what we can “see” becomes the story, making access to the voice powerful and important, yet this is something women in Spears’ position have rarely been afforded.