Indigenous Australians are the world’s most durable community. Their ancient traces are indivisible from our modern story. Some have accreted accidentally. Some have been collected systematically.

One of their greatest repositories is the National Archives of Australia. That being so, they’re under threat.

In early 2020, highly-regarded public servant David Tune, Secretary of the Department of Finance, delivered a comprehensive report into the challenges facing the National Archives.

Of particular concern were the fragile, irreplaceable film, photographs, magnetic tapes, and audio files that were determined to be facing imminent destruction, due to ageing and chemical degradation.

According to the Tune report, $67m allocated over seven years would enable the digitisation and stabilisation of these valuable records, and prevent their irretrievable loss.

What are these records, and why are they of interest?

From an Indigenous perspective, the National Archives contains some rare, indeed priceless, jewels that provide tangible links to the past. On film and magnetic tape are images, moving and still, of the Old People, in ceremony, singing, dancing, speaking.

These records have been valuable in native title claims, language revival, and history writing. They’ve been essential in reconnecting current generations to those who have passed.

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of these archives for Aboriginal people.

Read more: Australia’s history is complex and confronting, and needs to be known, and owned, now

The National Archives have played a vital role in helping people reconstruct their families in the wake of Indigenous child-removal policies.

There are also records of surveillance, observations from another time, when dissident Indigenous voices were subject to espionage.

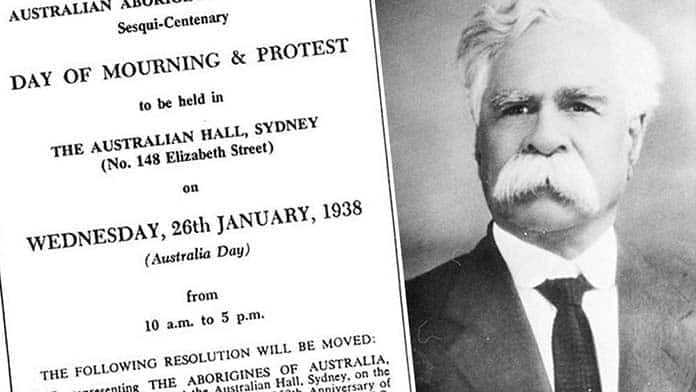

The retrieval of this material has enabled the building of a nuanced and detailed history of Aboriginal rights groups, and nationally-important figures such as the South Sea Islander activist Faith Bandler, or Yorta Yorta leader William Cooper.

These records provide evidence of Aboriginal people asserting their rights (as First Nations people) and their place within the nation. Aboriginal people have also featured in declassified ASIO files, providing an incredible record of who met, when, and what was discussed.

Aboriginal activist Gary Foley noted with some glee that ASIO “has done us a bit of a service” reacquainting him with old spy photographs, reminding him of old friends and long-forgotten participants in the struggle.

The NAA holdings document the shifting relationship between Aboriginal people and the Commonwealth government.

These records map changing attitudes and policies, illustrating the move from early protectionism to assimilation. The latter is documented in the glossy Commonwealth government pamphlets carrying titles such as “Our Aborigines”, and advocating assimilation and absorption policies.

Read more: The ‘frontier wars’: Undoing the myth of the peaceful settlement of Australia

Anyone interested in international responses to Australia’s treatment of Indigenous people, and Commonwealth governments’ reactions to these, need only look at the NAA collection.

The National Archives also contains many military records, evidence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ wartime activities, and their service to our country. These records are invaluable for understanding the role played by First Nations people during World War II.

Historians and authors have used the NAA records, particularly from the Northern Territory, to illustrate how important Indigenous labour has been to the success of the pastoral industries.

Other important records housed at the National Archives are medical records, particularly from the Northern Territory.

For example, researchers can locate records of Machado-Joseph disease, a neurological disorder that afflicts Anindilyakwa (on Groote Eylandt) and Yolngu (Eastern Arnhem Land).

Machado-Joseph disease, although usually rare, is found quite frequently in these Northern Territory communities. In the affected families, individuals experience late-onset disease (usually after having had their own children), and it’s always fatal.

This genetic disease was introduced by Makassan traders, and probably originated in either Portugal (Azores) or China. The concerned families want to know when and how the disease arrived, and how it might be predicted. They’re hopeful the answers might be found in the archives.

‘Valuable but fragile’ information

The National Archives of Australia holds valuable but fragile information about Indigenous peoples’ histories. Its value as a collection cannot be overstated.

Because the NAA is a repository of state records and administration, and of Commonwealth programs and initiatives, it’s a rich resource for social history, for records of the lives of ordinary people.

If anyone wants to write a history from the ground up, the NAA is a vital resource.

More than that, though, the NAA collections holds the stories of Australia, of each of us – it’s where we can seek to interrogate our pasts and seek reconciliation.

These are our archives – Indigenous and newcomers, settlers, immigrants, and recent arrivals. All have a stake in these collections.

Read more: Indigenous archaeology and the landscape knowledge that sustains oral histories

Preserving the archives is an act of patriotism. Among the degrading film, magnetic tape, paper archives and hundreds of kilometres of files, lies our histories.

We don’t know what future researchers might find, what stories they might tell about us, what thrilling and exciting discoveries are yet to be revealed.

I implore the federal government to fully commit to the digital transformation of these fragile records and provide the $67 million over the next seven years. It will maintain the integrity of our history, and the capacity for us to tell our stories about our nation.