In 2006, Norway was making half a billion dollars every month in profits from just one of its offshore oil rigs. Surely the person in charge of deciding how to spend such exorbitant amounts of money would be someone with a background in finance or economics or such.

But no, Norway figured a sophisticated computer could do whatever financial calculations were needed. So, they appointed a philosopher.

A philosopher, they argued, had the skills needed to think big, to think far ahead, and to think with compassion. An algorithm could largely tell them what shares to invest their profits in, but a humane, critical thinker was needed to consider if shares were even the best option for future generations.

The rapid and urgent response taken by governments and universities across the globe as they grapple with the fallout of COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted the arts.

Indeed, it’s surprising how many people in positions of power and influence, who often denounce the value of humanities and social science (HASS) subjects, have themselves an arts background – anecdotally, history seems a particularly productive major.

It's a worry, then, that the rapid and urgent response taken by governments and universities across the globe as they grapple with the fallout of COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted the arts.

As a case in point, the Australian government has clearly shown its preference for subjects such as agriculture, science and engineering by cutting their degree fees, while increasing fees for many arts subjects.

For instance, a maths degree will decrease 59% to $3950, while a communications degree will increase a whopping 113% to $14,500. Just as an aside, NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern graduated with a Bachelor of Communication Studies.

What constitutes a 'proper' choice?

The Minister for Education, Dan Tehan, pitched this fee change as encouraging students to make the "proper" choice:

“From next year, students will have a choice. Their degree will be cheaper if they choose to study in areas where there is expected growth in job opportunities.”

So where are we expecting growth in job opportunities? And I don’t mean where will this growth happen next year, or in 10 years, but what about in 50 years, 100 years? What jobs will our great-grandkids be doing? They might be nurses and lawyers, or maybe these jobs will be replaced by robots. They might be arborists or YouTubers. Who knows!

But what we can pretty safely say is that the skills of a philosopher, a historian and a communication graduate will always be important – critical and compassionate thinking, the capacity to communicate complex ideas to a diverse audience, an agile and resilient mind, and the ability to work well in a team will never go out of date.

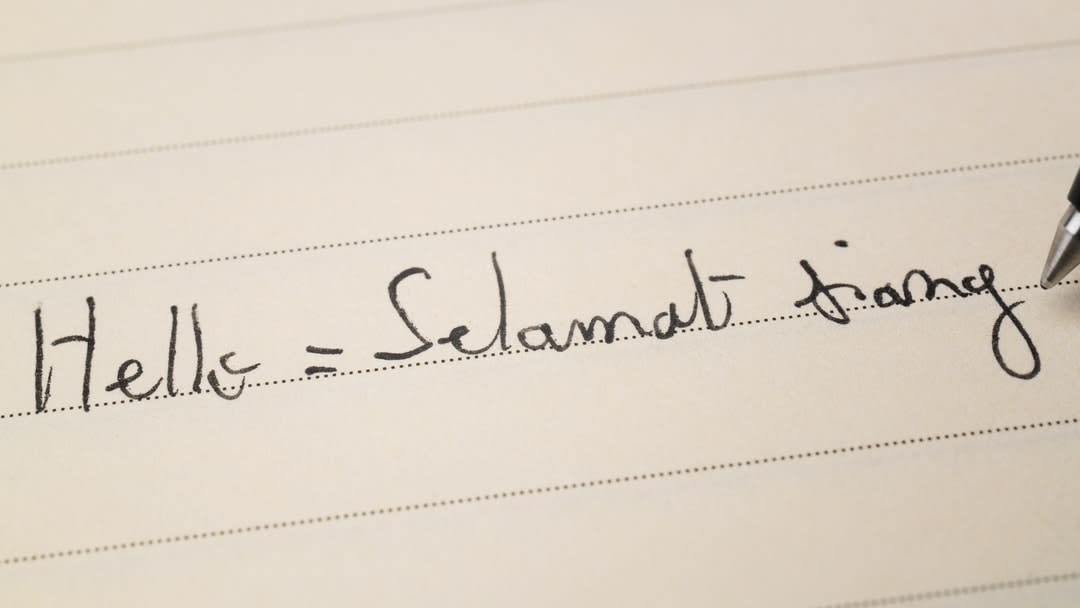

Amid the hiking of fees for HASS subjects, there's one glimmer of light – the study of languages has been recognised as vitally important to Australia’s future, and I couldn’t agree more. Google Translate can be OK – aside from the occasional translation of "jerk chicken" as "rude and inappropriate chicken" – but a program can never replace the connection made between people sharing a language.

From 2021, students studying Indonesian will see their fees drop a mighty 42%.

Indonesia, our largest neighbour with a population of almost 270 million, will see job opportunities galore for those with language skills. And Australia is rightly recognising Indonesia’s potential – from an Australian government loan just last week of $1.5 billion to Indonesia, to the Monash Indonesia campus opening its doors next year, it's an exciting time for bilateral relations.

With such optimism, we can only hope that universities that have supported Indonesian studies programs for decades can manage to keep an eye on the future, and keep their programs going.