Ennio Morricone’s death signals the end of an era for me – there's no singular figure who has had such a profound effect throughout my musical life.

As long as I've thought about music, I've been listening to music by Ennio Morricone. The musicians' love of other musicians’ work is a special thing – we seek to understand their methods, we carry their influence in our work, and we search for ways to honour them.

My father loved westerns. On most weekend afternoons in my childhood, Sergio Leone "spaghetti westerns" would be playing on TV with the volume up loud. I wasn’t interested in these movies back then, but I loved the music, and learnt to whistle after hearing Alessandro Alessandroni in the soundtracks to these films, especially For A Few Dollars More (1964). I even went on to compose music with whistling parts, such as the score for the dance piece choreographed by Martin Del Amo, Mountains Never Meet (2011).

Alessandroni’s guitar-playing also stuck with me, and I started to learn guitar when I was about 10 years old. His playing, and Morricone’s placement of it, went on to be an enormous influence on my bass-playing. The twangy sound, and regular, fast, repeated picked notes have stuck with me – you can hear them on tracks such as Your Smile Betrays You (Saint Dymphnae, Gata Negra), Little Thing (Ruby, Gata Negra), and Fetish #4 (Fetish, Cat Hope).

I didn’t get back to Morricone until after my tertiary music studies, when my friend Chris Hughes, who was busking electric guitar arrangements of Morricone on the streets of Berlin, where I lived in the early 1990s, made me a tape of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly soundtrack suite.

I was playing bass in a Sicilian guitar-rock band, The Quartered Shadows, at the time, and we did a cover of Morricone’s theme to The Sicilian Clan (1969) in our live shows. When I later moved to live in Sicily, I would find Morricone music everywhere, among my friends, in cafes and bars. The soundtrack to Once Upon a Time in America was played at my wedding there; it was on the car stereo all the time.

Many Italians I met in the rock scene were proud of Morricone, and loved his music. The "classical" musicians didn’t share the same passion, though he was making extraordinary concert music, too, with modernist pieces such as UT (1991) and works that aligned much more to his film oeuvre, such as Voci Del Silencio (2002). You can discover them in an article by Felicity Wilcox.

This view that film music is less in-depth than concert music is ongoing, and I often agree with the rationale. But for me, there's enough of Morricone’s film music that is unique, and provides a door into many other worlds – different timbres, orchestrations, and stylistic merging.

I've collected Morricone albums most of my adult life. I sought out scores, but the copyright around film music made them practically unobtainable.

My early academic career began with a desire to be a film-music scholar, off the back of this love of soundtracks that Morricone had started, but the difficulties of accessing this primary material saw me move onto other things.

I found other ways to engage this music – sampling the albums in music projects such as my noise duo Lux Mammoth, and pop band Gata Negra. The samples appear on albums such as Cage of Stars (1998) and St Dymphane (2001) in very abstracted forms, on tracks such as Ms Time (1997).

In 2011, the new-music ensemble I direct, Decibel, performed a "chamber cover" of the Morricone/Baez piece, The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti (aka Here’s To You) (1971), in the Music From A Dark Space (2011) program at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art.

Arranged from an ear transcription by ensemble member Stuart James, it was a great way to get close to the music and its production, untangling the interwoven experimental sounds, recording effects, the careful mix of electronic and acoustic instruments.

The Decibel version features mezzo soprano Caitlin Cassidy, a small choir, bass clarinet, bass guitar, electric guitar, keyboard, drum set, viola and cello. Much later, I made my own attempt to quote those great guitar, cor anglais and harmonica textures for which Morricone was so renowned in a composition of my own, U Mangibeddu Beddu (2018), a piece about my time in Sicily. The wordless singing that was featured in many of Morricone’s soundtracks, influenced heavily by Alessandroni’s I Canti Moderni, was a major inspiration for the concept of my wordless opera, Speechless (2019).

Perhaps most importantly, Morricone showed me the value of the musician-composer combination.

His career began as a trumpeter in jazz bands, but it was his work in Franco Evangelisti’s experimental music collective, Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, aka Il Gruppo (1964-1980), that was key for me. This band featured in some of his more radical soundtracks – notably, one of my favourites, Gli occhi freddi della paura (1971). Il Gruppo was playing music by my favourite composers, such as Luigi Nono and Giacinto Scelsi, as well as improvising around their ideas, best exemplified in the piece Omaggio a Giacinto Scelsi.

They were experimenting with electronics and piano preparations, and the idea of the composer’s collective held up by Evangelisti – thinking, planning, playing, improvising and composing within the group – is a founding principle of my direction for the Decibel new-music ensemble. There's a great documentary of them here, which starts with them bumping into their equipment for a show in an art gallery, in suits – I can relate to that!

Hearing Morricone working across styles, from pop songs for artists such as Mina (who can forget Se Telefonando?), and ghost-writing a whole range of other materials, showed me that one’s practice could span all these directions.

He often developed themes and ideas across multiple works – for example, melodic ideas and orchestrations from the spaghetti westerns appeared more than 10 years later in the romantic drama Days of Heaven (1978). His background as a performer meant he understood the value of individual instrumentalists, as evidenced in his engagement of Alessandroni and Il Gruppo, but also George Zamphir, exemplified in the very emotive Cockeye’s Theme in Once Upon A Time in America (1984).

His music was engaged for westerns, romances, horror, giallo (mystery fiction) and more.

Knowing his music was played on Leone’s film sets during filming taught me music could lead, not just follow, cinematography and editing.

This scene from Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) will remain one of the best from the Leone/Morricone collaborations for me, centred on the harmonica and its reliance on breath. A close second would be the use of the glockenspiel death signal at the end of For A Few Dollars More (1965).

A student of the modernist composer Gofreddo Petrassi at the Conservatorio Santa Cecilia in Rome, Morricone was the master of low brass, warm string sounds, percussion, and combining rock and classical instruments, improvisation, pop and orchestral style.

Not all of the soundtracks were masterpieces, but there were enough to matter. Tracks such as the title music for the film Revolver really showcase his skill for syncopated rhythm, brass writing, and a signature cross-stylistic polyphony.

Who can forget the distorted guitar, string and harmonica combination at the end of Once Upon A Time in the West, which rolls into choir, brass and drum kit? The organ solo in For a Few Dollars More (1965), the vamps in Indagine su un Cittadino al di Sopra di Ogni Sospetto (1971), the sparse and angular sounds against the Penderecki-style strings of Cat of Nine Tails (1971), the amazing drumming in Slalom (1965), the Rickenbacker bass and grand piano pairings in A Fistful of Dollars (1964), the climatic moments of the final scenes in The Good the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), paired with those intense Leone close-ups.

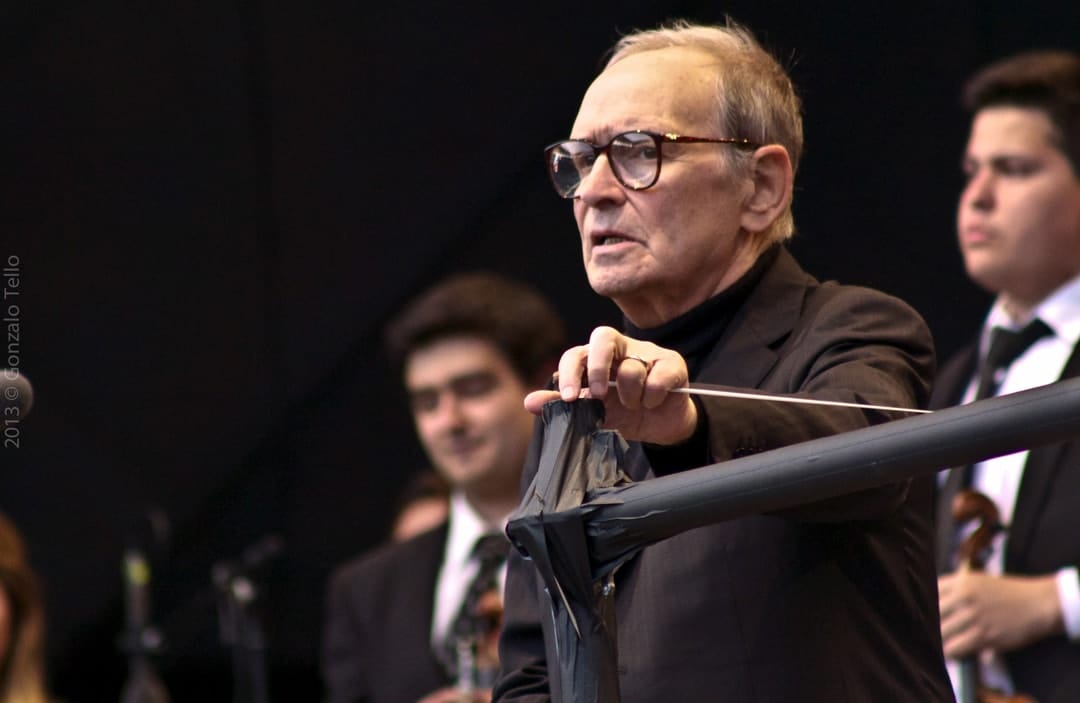

I only ever saw Morricone in person once, when he conducted a concert of his music performed by the Western Australian Youth Orchestra – an orchestra I used to play in – in Perth in 2012, travelling with his choice of electric bass, guitar and drummer, and singer Susanna Rigacci. It was incredible.

Thanks for the fun ideas, Ennio, and for the soundtrack to my life. Your success was rightfully the envy of composers everywhere.