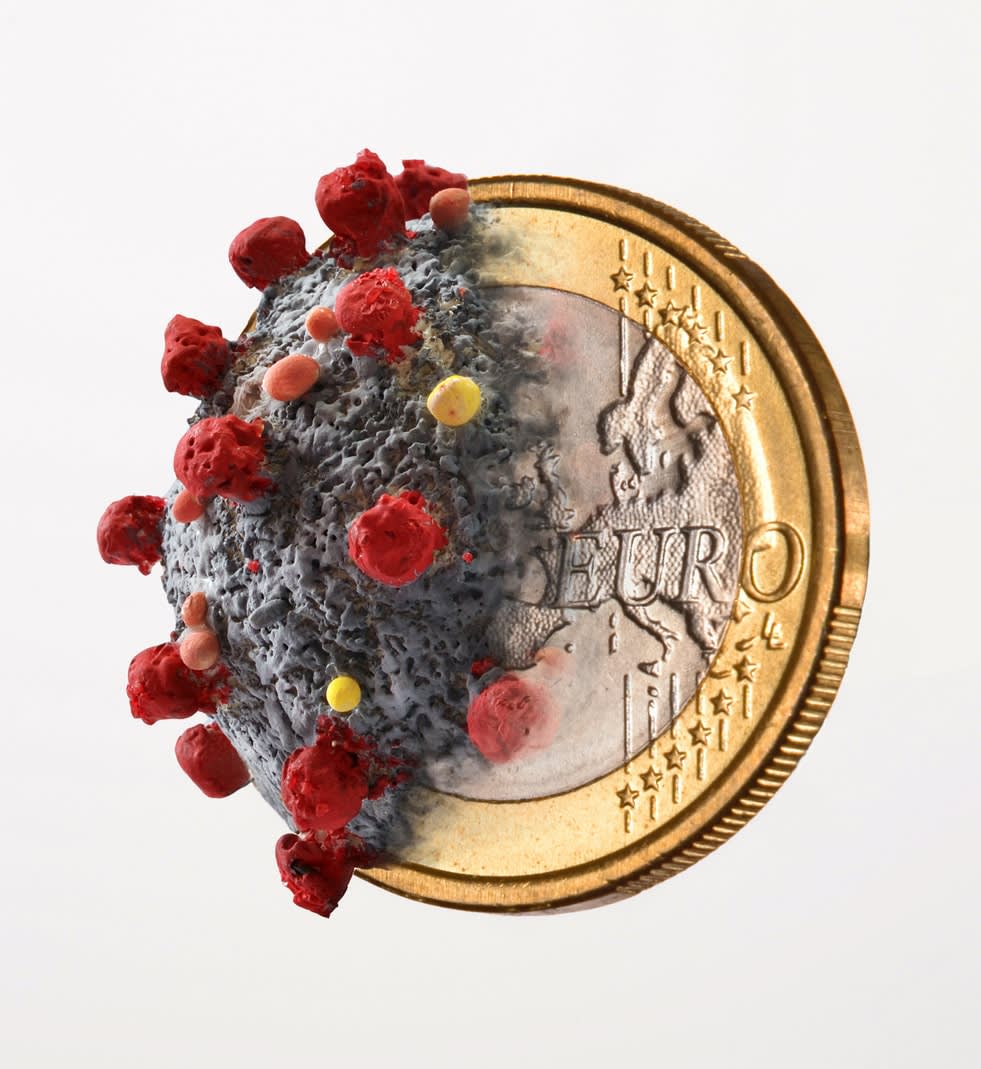

COVID-19 is devastating Europe. The continent has more cases than anywhere else, and the EU is divided over how to respond. The virus poses the most serious threat to European unity since WWII.

The EU has already provided billions to help its member states cope with COVID-19. After two weeks of negotiations over the Easter break, Europe’s finance ministers announced a €540 billion fund to protect workers and businesses. This was in addition to a €750 billion rescue package already announced by the European Central Bank. An additional recovery fund of up to €500 billion has also been mooted for when the pandemic is over.

But will these measures be enough to save the EU?

“Behind the natural disaster of the pandemic, there’s a political failure,” says EU specialist Dr Natalie Doyle. “One that is specific to Europe, because it locked itself into austerity after the Global Financial Crisis as a result of the economic philosophy that inspired the creation of the euro, which gave the ECB a very narrow brief of monetary stability and enshrined the idea that debt is always a moral hazard, that states must be disciplined by the financial market on which they must be made to rely exclusively.”

Call to ditch austerity, embrace debt

Southern states are now demanding that the EU abandon its commitment to austerity. They want debt to be embraced as a means of stimulating the economies decimated by COVID-19.

Most importantly, they want the debt to be shared across countries to avoid the mistake made at the time of the GFC, when it became apparent to hedge funds and the like that there was little solidarity among member states of the kind found within federal states such as the US or Australia.

For instance, Spain’s Prime Minister, Pedro Sanchez, wrote in an open letter in early April that “Europe must build a wartime economy, with measures to support the public debt that many states, including Spain, are taking on”. He said the action to rebuild the continent’s economies must continue after the health emergency is over.

The Sanchez letter called for a new “Marshall Plan”, the name of the US-funded aid package that rebuilt Europe after WWII. Germany’s war debts were forgiven under the plan, allowing it to create the strongest economy in Europe.

Sanchez proposed that the Europeans fund their own package this time around, by issuing “corona bonds”.

Even Mario Draghi, the former Goldman Sachs banker who managed the European Central Bank during the Greek crisis, has said the economic destruction caused by COVID-19 demands a revolutionary new approach.

In an article published in The Economist, he wrote “the challenge we face is how to act with sufficient strength and speed to prevent a recession from morphing into a prolonged depression made deeper by a plethora of defaults leaving irreversible damage”.

He advised that “the loss of income incurred by the private sector and any debt raised to fill the gap must eventually be absorbed wholly or in part onto government balance sheets. Much higher public debt levels will become a permanent feature of our economies, and will be accompanied by private debt cancellation.”

Draghi has previously challenged European economic orthodoxy. During the Greek crisis, he allowed the European Central Bank to print more money – a device known as quantitative easing – overriding German objections.

“At the time, Draghi said that the bank would do anything it would take to save the euro,” Dr Doyle says. “And when he said that, he immediately regained the confidence of the financial markets, countering the mistake made by the political leaders in their obsession with eliminating debt.”

The EU’s economic response to the pandemic is determined by the rules that place limits on its capacity to provide monetary stimulus, Dr Doyle says.

During the GFC, the EU imposed draconian financial measures on its most affected states – the debt-burdened PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain).

The EU failed to fund a continent-wide response unit to a possible future pandemic proposed by the European Commission after the Ebola and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreaks.

In response to the Greek debt crisis of 2011-12, an intergovernmental agreement, the European Fiscal Compact, was endorsed, hardening the conditions imposing limits on state debt first established in the late 1990s in the lead-up to the creation of the European monetary union. This new agreement established the strategy that would be used to manage the debt – loans rather than bailouts – and with oversight from the IMF.

It gave the European Commission the power to inspect the budgetary arrangements of its member states, in a bid to limit future debt blowouts.

Other states saw how Greece was forced to sell public assets and casualise its workforce under the pact. They do not want to suffer the same fate now, to see their public finances managed by technocrats from the so-called Troika (the EC, ECB and IMF).

The proposed corona bonds, or their equivalent, would not require this kind of scrutiny, and would encourage the development of a common fiscal policy – something that many economists have long said was needed for the monetary union to function optimally.

The founding treaty for the European Union contains a clause that states the rules can be changed if extraordinary circumstances force a country to incur a debt. But in a meeting attended by EU finance ministers in late March, the German and the Dutch representatives didn’t consider the COVID-19 emergency “extraordinary” enough.

The havoc wreaked by the virus in Europe cannot simply be viewed as a “natural phenomenon”, Dr Doyle says. The toll it’s taking has also been influenced by politics and economics. The effects of post-GFC austerity have left Spain and Italy in a weakened state, and the disagreement over the corona bonds must be understood in this context, she explains.

Before the GFC, northern Italy, for instance “had one of the best health systems in Europe”, she says. But Italy’s capacity to cope with COVID-19 has been compromised because “of all the austerity measures, the need to reduce public spending imposed on all countries of the eurozone”.

Smaller budget cuts have protected Germany

Germany, where the number of infections is also high, has so far not experienced the same loss of life as its neighbours, and that’s because Germany, with its more robust, export-focused economy, did not cut its health budget to the same extent, Dr Doyle says.

In addition, southern European countries such as Italy and Spain have long experienced high rates of youth unemployment exacerbated by the GFC, as a result of their struggle to maintain exports, with the euro being overvalued for their economies, while it’s generally undervalued for the northern countries.

This, on top of other factors, has certainly contributed to their low birth rate, which has left them with an ageing population, and a society more vulnerable to the dangers of COVID-19 both medically and economically, Dr Doyle says. (Germany also has a low birth rate, due to its casualised workforce and the difficulty of accessing childcare.)

To make matters worse, the European Union failed to fund a continent-wide response unit to a possible future pandemic proposed by the European Commission after the Ebola and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreaks.

The EU’s member states “refused to give money to it”, she says. “Why? Because they had to go back to their individual electorates while they were cutting public spending.” In those circumstances, preparing capacity to cope with a hypothetical threat was a “very hard sell”.

Record low support in Italy for the EU

The Easter emergency package was welcomed by the southern states. But will it be enough? Support for the EU in Italy – an industrial power and a founding member of the EU – has dropped to historic lows (in a recent poll, 88 per cent of Italians said they didn’t believe the EU had helped Italy during the crisis, and 67 per cent saw EU membership as a disadvantage).

Dr Doyle outlines one scenario. “The Italian government could decide that they're going to go for a stimulus package of the same order that you've seen in Australia, and support the population through a wage guarantee, say. And then go into debt, issue bonds. Of course, the countries of the north would object ... So what will Italy do? It will say, ‘Sorry this is an extreme situation’. At that point, the eurozone fractures.”