After more than a year of campaigning, the primary elections to determine the 2020 presidential nominees are about to begin.

On 3 February, Iowans will vote in the ‘first-in-the-nation’ caucus, closely followed by the New Hampshire primary on 11 February. These two states play a powerful role in winnowing the field of candidates to a handful of legitimate contenders, and with a dozen Democrats still vying for the chance to defeat President Donald Trump, victories in these states are vital.

But why Iowa and New Hampshire? Why do two of the least diverse states in the union play such a pivotal role in determining the nominees for the highest office in the land?

Tradition? Yes – but not as longstanding a tradition as one might think.

Primary origins

The first presidential primary, in its modern form, took place in 1972 after the previous Democratic National Convention four years earlier descended into chaos.

In 1968, only 14 states had held popular elections to determine the party's nominee prior to the convention, with party insiders playing the role of kingmaker behind closed doors. Then-incumbent vice-president Hubert H. Humphrey was ultimately nominated, despite his lack of participation in any of the 14 voting states. Humphrey’s backroom nomination elicited a sense of outrage among Democratic ranks, and caused the party to make its nominating process more participatory, transparent and spread out. This system worked for the Democrats, and Republicans soon followed suit.

The primary system

Presidential primaries are long and meandering. Between February and June, voters from all 50 US states, five territories and the District of Columbia will participate in either primaries or caucuses, while candidates attempt to garner voters’ support to secure a majority of delegates to their party’s national convention.

So, in fact, both the nominating process in entirety and the nominating processes of some states are referred to as a ‘primary’.

The latter refers to the way by which states vote for their preferred candidates. Some states, such as New Hampshire and South Carolina, hold a primary election, whereby voters select their preferred candidate, and results are tallied to determine a winner and apportion delegates.

Other states, such as Iowa and Nevada, hold caucuses, a more involved process where ‘caucus-goers’ convene in venues across their states to openly display their preferences and convince others to change their minds.

The Iowa caucus, with the first votes cast, garners much attention and illustrates how this electoral process can operate. Iowan caucus-goers split themselves into groups by preferred candidate. For a candidate to be considered viable, they must receive the support of 15 per cent of those present – this is known as the viability threshold. Caucus-goers supporting candidates who don't meet this threshold must either shift to a second preference or convince others to join their group until all candidates that retain support have at least the 15 per cent threshold. Once voting has concluded, delegates are apportioned to the candidates deemed viable.

Still with me?

Now, who or what are these delegates?

Delegates are individuals selected to represent a group of constituents on the understanding that they will support a given candidate at the convention. Each state has a predetermined number of delegates, which are awarded to candidates proportionally in accordance with the state's vote. To claim the nomination, one candidate must receive the support of a majority of delegates at the convention. This majority is typically clear prior to the convention.

Banking on Iowa and New Hampshire

Iowa’s status as ‘first in the nation’ is by consequence of federalism. Each state determines its nominating process and, leading into 1972, Iowa’s was among the most complicated, such that the Iowan Democratic caucus simply began early.

Candidates quickly realised that pouring resources into this early-voting state could elicit momentum for their campaign. Such tactics have worked wonders for fledgling candidacies, including for Jimmy Carter in 1976, who catapulted from obscurity to an Iowan victory, and the presidency.

The New Hampshire primary is considered another avenue to build campaign momentum. Since the 1950s, New Hampshire has been among the early-voting states, and its status as the first primary (as opposed to Iowa being the first caucus) is enshrined in state law. In a similar manner to Iowa, candidates bank on New Hampshire to propel their status from unknown to frontrunner.

Both these states simply demand retail politics – whereby candidates campaign in a more personal manner by meeting voters to garner support. This provides a unique opportunity to these states, and yet, although Iowans and New Hampshirites defend their ‘first’ status vehemently, their stranglehold on early-voting is not without contention.

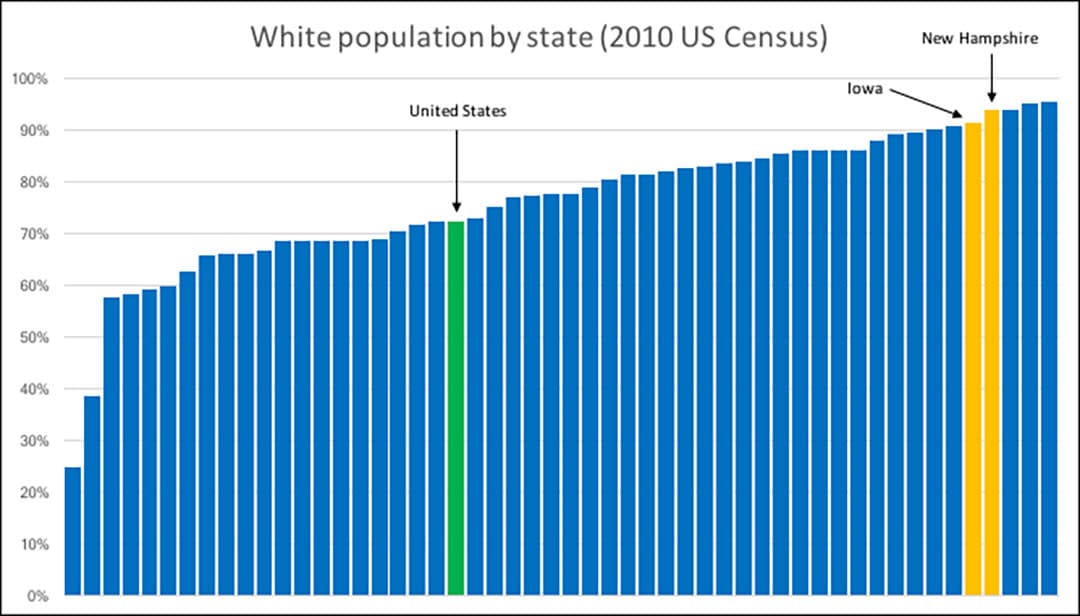

In the 2010 Census, New Hampshire and Iowa were 94 per cent and 91 per cent white, respectively. The perceived whitewashing of early-voting has drawn criticism on the contention that these states do not reflect America’s diversity, as seen in the graph below.

This lack of diversity is particularly pertinent to the Democratic Party, whose support is strongest among minorities. The present compromise consists of the more demographically diverse Nevada and South Carolina voting third and fourth, respectively.

Who's in for 2020?

Political folklore considers that ‘three tickets’ emerge from the Iowa caucus –an adage that contends the top three finishers in Iowa are the few with a chance of victory. Those that fail in Iowa rely on a strong finish in New Hampshire to energise their campaign.

So, coming into 2020, who are the leading candidates?

On the Republican side, President Trump’s re-nomination appears to be a fait accompli, despite the ongoing impeachment saga.

For Democrats, the leading liberal lights, senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, are not only feuding, but dividing the party's left-leaning supporters.

At the same time, Senator Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg are seeking to wrest the moderate lane from former vice-president Joe Biden. The remaining candidates, perhaps aside from billionaires Tom Steyer and Michael Bloomberg, seem destined to fall out of the fray.

The Midwesterners, Klobuchar and Buttigieg, are placing much of their hopes on a strong showing in nearby Iowa. Warren and Sanders, as New Englanders, will be seeking favourable results in their neighbouring New Hampshire. And then there is party elder, Biden – consistently atop national polls and competitive in the early states.

Now, all that remains to be seen is whether being a projected 'frontrunner’ is a self-fulfilling prophecy, or whether a new leader can emerge from the pack.