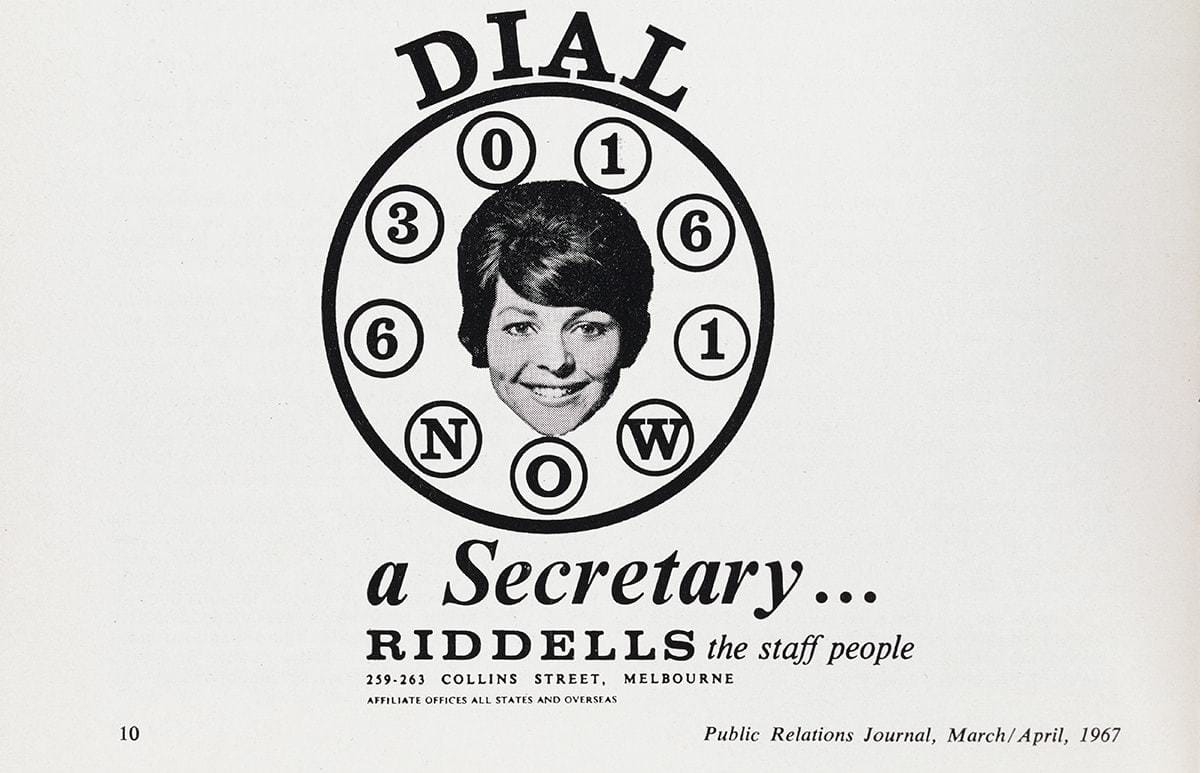

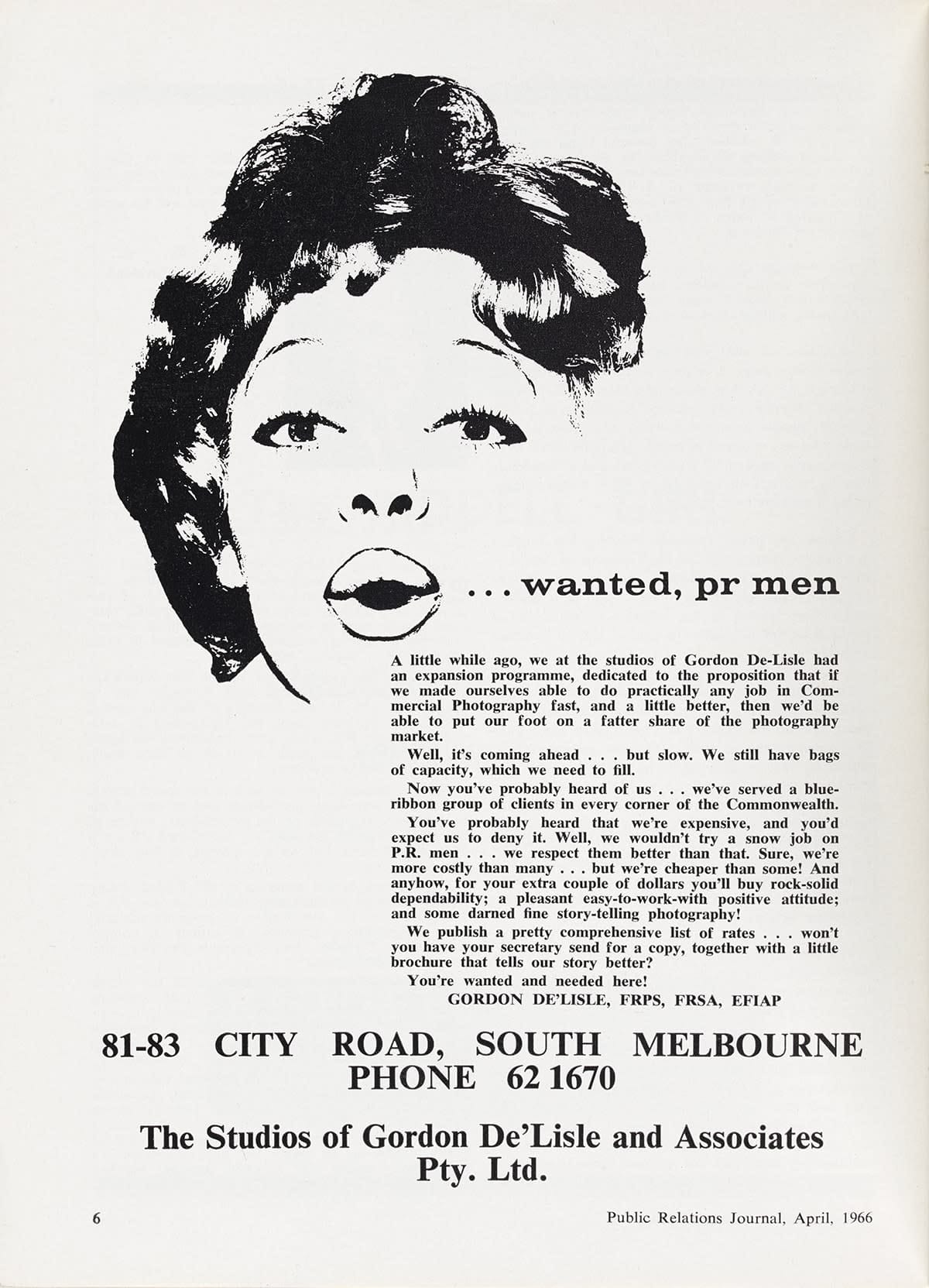

There were more representations of female bodies and body parts than expert female public relations officers in the trade media between the mid-1960s and early 1970s, despite evidence that women made up a quarter of professional membership in Victoria in 1968.

I analysed the Australian Public Relations Journal (renamed Public Relations Australia in 1968) between 1965 and 1972 to understand the changing role of women in public relations.

Today, the occupation is a highly feminised field, with women making up 73 per cent of the workforce. This research illuminates the ways women were included in the trade media of an occupation seeking professional status. The professional project is threatened by the inclusion of women, so this historical work offers some insights into contemporary tensions around gender in the Australian public relations industry.

The journal was produced by the state-based public relations institutes of Australia, the forerunner of today’s national Public Relations Institute of Australia (PRIA); in 1966, its production moved from Sydney to Melbourne, and the new editors chose to showcase the work of designers, illustrators and photographers.

Together with advertisements aimed at secretarial staff that include disembodied heads and fingers, these images representing the female body were common. For example, there were artistic representations of naked bodies on one cover, and illustrations of a woman’s breast and mouth to illustrate an article likening television to a vicious mother.

Supporting roles

In addition to bodies and body parts, women are mostly represented in roles that supported and facilitated men’s careers. Wives are mentioned because they were often welcome at social activities organised by the professional body. In fact, in 1968, half of the female members of the professional body were married, suggesting public relations offered more employment opportunities for married women than many other occupations at that time.

The star wife was Sylvia Dyer (nee Birdsey), whose marriage to Donald Dyer featured in the journal in 1967. Although never a member of the PRIA, her fundraising and organisational support roles at state and national levels were later honoured with a PRIA life membership.

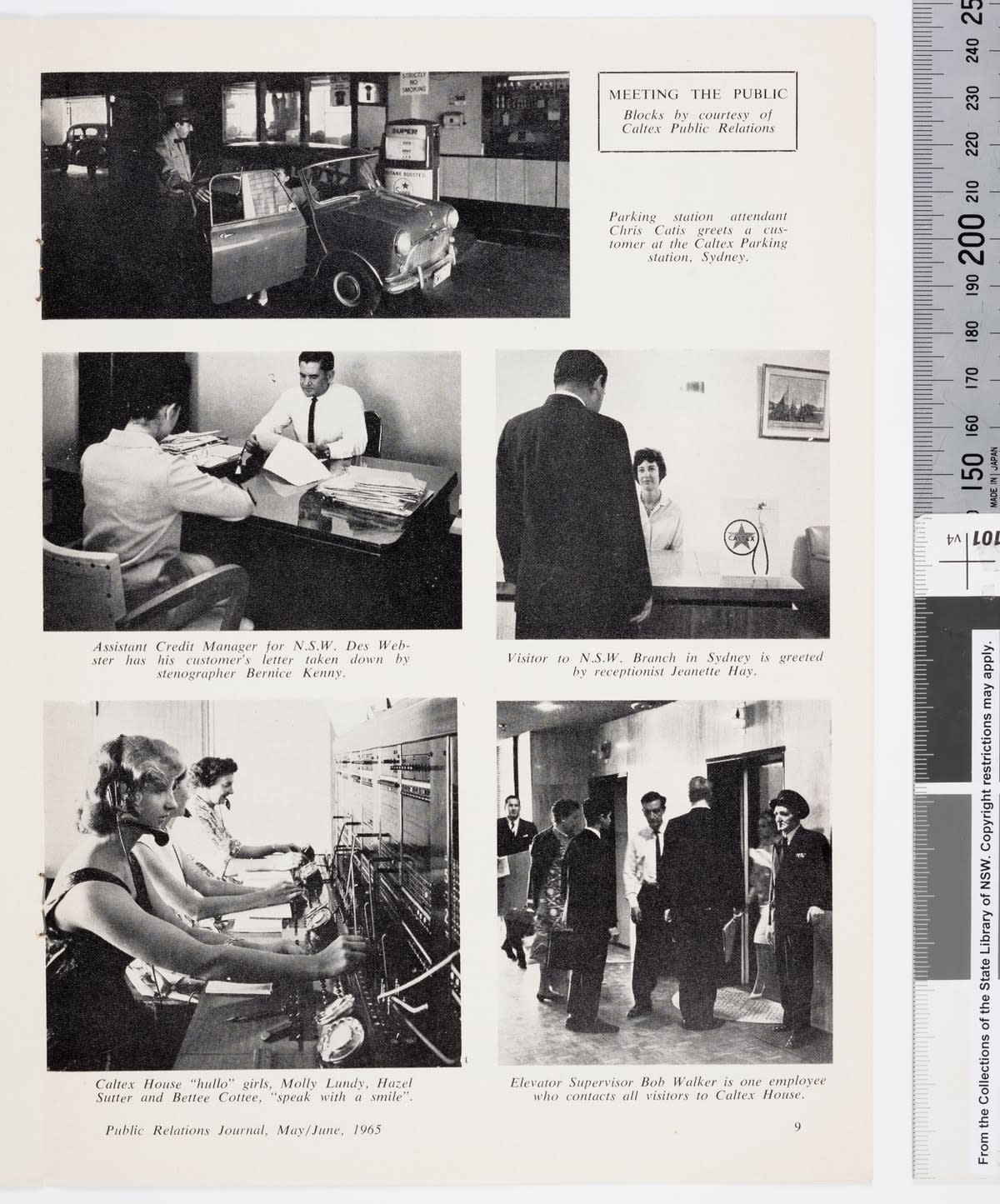

The most prominent references to women are in service roles – secretaries, stenographers, telephonists, receptionists, and even a nurse and an air hostess feature in the journal pages.

This research highlights the marginalisation of women in trade media in precisely the years that coincided with the rise of the women’s liberation movement and campaigns for equal pay in Australia.

Professor Jacquie L’Etang found that technical, lower-paid work performed by women was largely invisible in the UK trade media between 1948 and 1970. In contrast, the Australian journal sometimes acknowledges the supporting, non-professional work of the office wife.

For example, “Meeting the Public”, a full page of photographs provided by the Caltex public relations team, shows a female stenographer taking down a customer letter from her male boss, a female receptionist greeting a male visitor, and three telephonists, the “Hullo Girls”. A case study refers to “the Gold Coast’s public relations team [a PRO and two stenographer assistants]”, where in 1968 the male public relations officer spearheaded a successful campaign to support regional tourism.

More than half of female members in 1968 were full professional-grade members. Women worked in diverse roles across hospitality, charity, travel, manufacturing, retail and public sectors, and often set up their own consultancies.

However, this diversity isn’t always reflected in the journal. From 1965 to 1972, the journal features only a handful of references to senior female practitioners. There are, for example, photographs of Jessie Fawsitt, who worked for British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) from the late 1940s, at a London event for BOAC public relations officers from around the world, and Kay Brownbill, vice-president of the South Australian professional institute and public relations officer for The Advertiser, carrying paintings for the newspaper’s art exhibition.

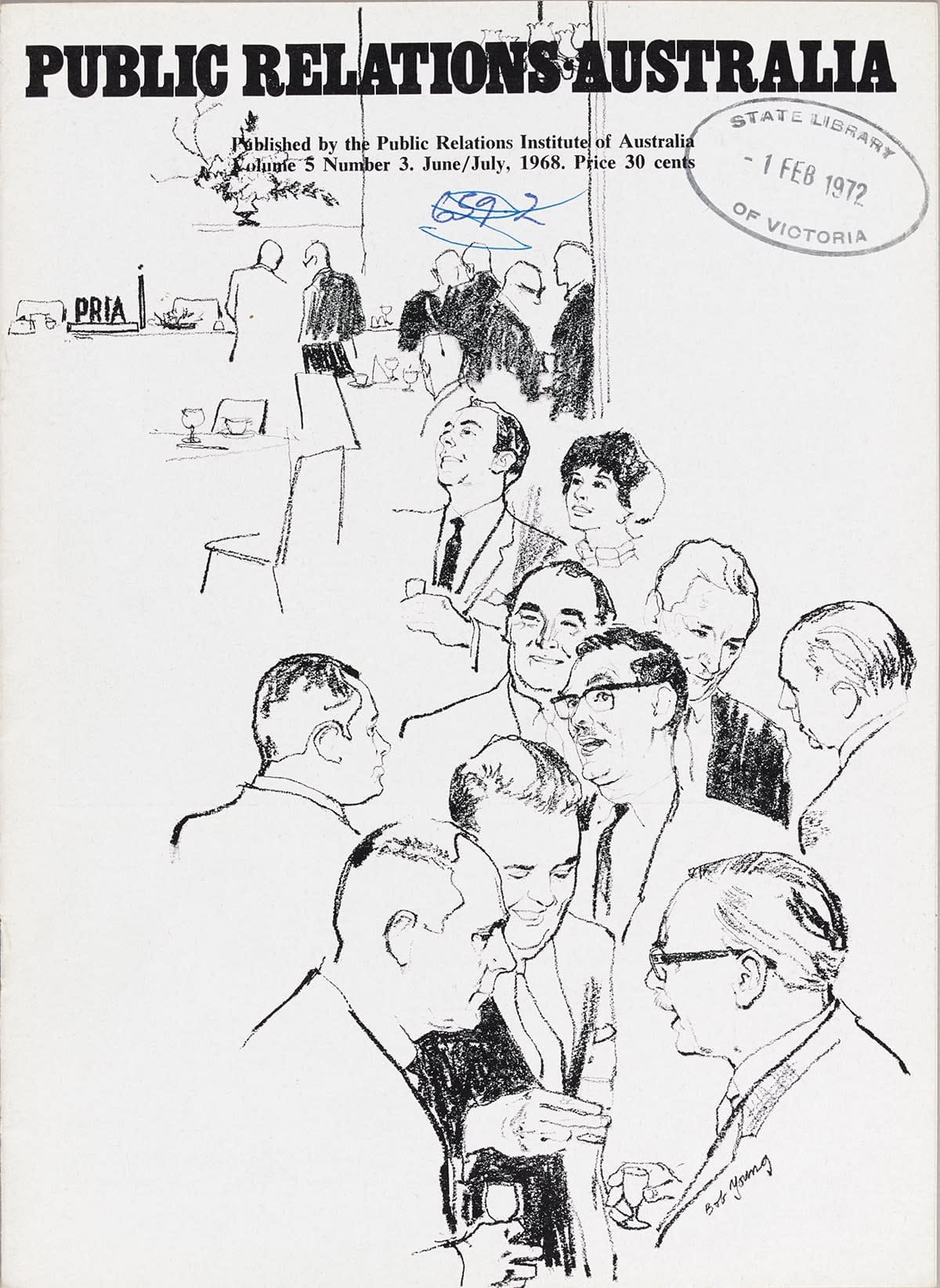

My favourite image of a woman “at work” shows Penny Cresswell, a Tasmanian council member, state president and national councillor, depicted in an illustrated cover as the sole woman in a room full of men at the national council meeting in 1968.

This illustration is significant for two reasons. First, in that year, Tasmania was the only Australian state with women on its council and/or a female president. In contrast, women were better-represented on the state councils and newsletters in the early 1950s. Second, the illustrator, Bob Young, even inserted the Victorian president, who was unable to attend the event. Not only are women, with one exception, absent from the national delegates’ lunch, but an absent man is still included.

This research highlights the marginalisation of women in trade media in precisely the years that coincided with the rise of the women’s liberation movement and campaigns for equal pay in Australia.

Women were not just underrepresented in the journal, but as presenters at industry conferences, state councils and professional-grade memberships. These activities helped define industry norms and establish claims for professional recognition.

Highlighting objectification

The body theme that included nude photographs, illustrations of women’s breasts, and other body parts such as fingers and heads to advertise secretarial services, points to other research that highlights the objectification of women and the framing of feminised labour as an extension of the body. Typically, women’s work is confined to support roles, or constructed as non-professional work.

The ways women are included in the journal ensured professional legitimacy wasn’t threatened. However, their restricted representation points to longstanding fissures along gender lines that continue to influence understandings of public relations’ professional practice and occupational identity.

There’s almost no research regarding women working in public relations in Australia in the period immediately prior to the 1970s and 1980s, when the occupation underwent a sustained period of feminisation.

Given the widespread recognition of the feminisation of public relations, and the corresponding devaluing of “women’s work”, this study highlights the need for a more historically informed position on women and public relations, and the significance for contemporary promotional work today.

All images are reproduced with the permission of the Public Relations Institute of Australia.