Of the potential challenges raised by the impending era of "smart" machines, one that hasn't received the attention it deserves is the threat of "social de-skilling".

To take an extreme example, consider the proposal by MIT’s César Hidalgo to automate citizenship by offloading voting onto personalised "digital agents". Informing oneself about the issues takes time, effort and background knowledge, which is why, for Hidalgo, democracy faces a problem of "cognitive bandwidth".

Information overload combined with partial or misleading information helps explain why people end up voting for candidates who, in some cases, don't even reflect their own policy preferences.

As is often the case when it comes to "too much information" combined with "not enough time", one ready solution is to hand over the decision to automated systems.

Hidalgo envisions the development of well-trained AIs that can sort through the welter of news coverage and policy papers to learn which candidate fits best with our individual preferences and priorities. The same systems that pick movies on Netflix, books on Amazon, and news stories on social media can be tasked with picking political representatives.

Perhaps such systems would even incorporate the forms of collaborative filtering that already shape our information worlds: "People who liked candidates like the one you voted for last time around, also like candidates such as these …"

Taken to the limits, such systems could become our digital representatives, sorting through political debates to determine which side we’re on. As Hidalgo puts it: "We could have a Senate that has as many senators as citizens" – but only, of course, if the senators are not automated.

Setting aside, for a moment, the question of who would build and own these political bots – and how that might influence their recommendations – we might readily concede the possibility that a well-crafted AI could predict our political preferences with a high degree of accuracy.

Relieved of the burden of learning about the candidates, we might gain more time to spend on Netflix or at work, on hobbies or with family. But there's a fundamental misunderstanding built into this conception of civic life. We don’t educate ourselves about the issues only to exercise our vote every few years.

Voting is obviously the decisive moment in democratic self-governance, but it builds on the underlying foundation of some level of ongoing engagement with civic life. Discussion and debate about public issues helps develop civic skills and dispositions, including the ability to recognise the claims of others, and the shared interests that unite us despite our apparent differences.

The rise of digital technologies and devices that foster hyper-personalisation of information, entertainment and consumption makes it easier to ignore our underlying interdependence and commonality. Letting these same devices vote for us would make it easier than ever to imagine that voting is simply one more consumer choice, rather than the tip of the civic iceberg.

Relieving us of the burden of informing ourselves about the issues and discussing them with others doesn't make politics more "efficient", it undermines its conditions for the exercise and development of our civic faculties, exacerbating the current trend towards political polarisation.

Careful what we wish for

We don’t need to rely on hypothetical examples to discern the ways in which profoundly social activities – the ones that foster and remind us of our social interdependence – are being offloaded onto automated systems.

Artificial intelligence is already playing a growing role in job screening and interviewing, in university admissions, security screening and policing, and in deciding what we see, listen to, and watch online.

The promise of this next generation of information technology extends the promise of automation beyond routine physical tasks to embrace social processes of evaluation and decision-making. We might describe these systems as means of automating the process of judgment.

The promise of these emerging forms of automation is that we can pursue our individual interests and goals unencumbered by the social processes that can be offloaded onto dedicated machines. Although there are certainly benefits to these systems – searching the internet, for example, would be impossible if humans had to do it on their own – we need to consider carefully which activities to shield from the imperative to automate.

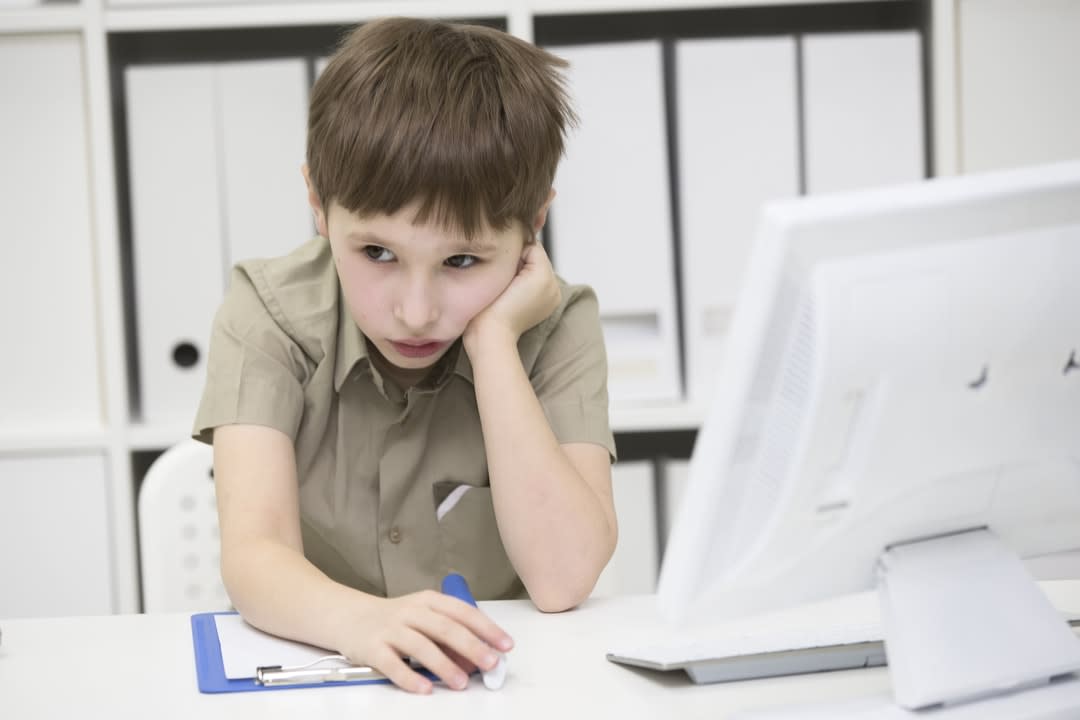

Consider, for example, the recent coverage of the challenges faced by Summit Learning, a computer-based, customised teaching system funded and supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Summit is the latest attempt to deliver on the Silicon Valley promise of customised instruction. The stated goal is to address the problem of expanding class sizes and tightening budgets (being eaten up by technology spending) by providing every student with the experience of individualised curriculum and tutoring via computer.

This version of automated instruction is the extension of Hidalgo’s version of digital politics into the classroom – an automated teacher for every student. If we balk at the subtraction of the human element from education – and politics, Hidalgo reminds us –we have a tendency to get used to the way machines help us do things over time.

Summit Learning introduced its program on a trial basis to a number of public schools in the US to decidedly mixed reviews.

In one Kansas school, several parents withdrew their students because the replacement of human contact hours with screens reportedly led to depression, anxiety and fatigue on the part of students.

A significant majority of parents (80 per cent) expressed concern about the program in a school survey, and one parent reported that learning had become such a solitary endeavour that her daughter wore earmuffs to block out the sound of other students. In Brooklyn, New York, students in one school staged a walkout to protest against the program, complaining that it "kept them busy at computers rather than working with teachers and classmates".

To acknowledge the importance of human interactions in the classroom is not to dispute the benefits of online or solitary learning – YouTube is great for showing you how to change a shower head, fold an origami crane, or learn the harmonica, and we've long encouraged students in the sometimes solitary pursuit of reading. However, we should think twice about surrendering the curriculum to AI when it comes to the crucially important role of education in helping students understand the world around us in order to change it for the better.

Shared social practices

One important argument in favour of automated decision-making is that it may help improve efficiency and reduce bias in important areas, from employment screening, to loan approvals, to prison sentencing (although one of the most high-profile cases of automated bias has been in a risk-assessment system used by some US courts). This is certainly a welcome development, but we need to recognise that in bypassing human decision-makers it leaves their biases and prejudices untouched – and these biases have a way of working themselves into the systems humans build.

Try as we might, we're unlikely to build automated systems that are fully independent of the assumptions and biases we bring to them – which means we need to address these biases at the human level, rather than imagining that the machines will resolve them for us.

In the end, important decisions (about whom to hire or convict, whom to promote or admit, whom to elect or fire) are inseparable from the underlying social processes that lead to them. If we delegate the decisions, we risk atrophying the skills and practices that enable them.

A functional society requires the forms of mutual recognition that foster an understanding of shared interdependence and common interests. Such an understanding is formed through shared forms of social practice.

This claim sounds abstract, but we can see it manifesting concretely, for example, in the increasing levels of political polarisation that accompany the automated curation of news and information online.

A word of warning

The growing public profile of hate groups and the degradation of the conditions for public deliberation are contemporary symptoms of civic de-skilling.

A defining irony of automated decision-making is that one of the promises of the digital era has been to overcome the alienated forms of de-skilled labour that characterised industrialised automation.

From the playground workspaces of Google to the rise of social media celebrities and social influencers, the online economy has promoted itself as creative and participatory – an antidote to drab office work and routine factory labour.

After liberating us from "uncreative", routine work and rote repetition, digital automation promises to relieve us of creativity and sociality itself – of the decisions that embody and reproduce our social and political commitments.

Now, however, after liberating us from "uncreative", routine work and rote repetition, digital automation promises to relieve us of creativity and sociality itself – of the decisions that embody and reproduce our social and political commitments.

As we face this new era of automation, we should retain the lessons of the previous one. The de-skilling of labour coincided with the concentration and centralisation of control over decision-making processes in the workplace.

Now that the decision-making process itself is being automated, we should be wary of the concentration of power in the hands of those who control the databases and write the algorithms. They'll be deciding not just how products get built, but how society runs.

We'll need all the civic skill we can muster to provide the necessary accountability for the ways in which they seek to transform our social and political worlds.

Find out more about this topic and study opportunities at the Graduate Study Expo