In the second half of 2010, a survey was initiated from Monash University in which Australian political historians and political scientists were asked to rank the performance of past Australian prime ministers.

We did not include the three caretaker prime ministers — Earl Page, Francis Forde and John McEwen, each of whom served in the office for a matter of days or weeks following the death of an incumbent.

This left 23 prime ministers, beginning with Australia’s inaugural national leader, Edmund Barton, and finishing with Kevin Rudd, who had been deposed from office only months before the survey was conducted.

Our experts were asked to grade the overall performance of each prime minister in one of five categories (outstanding, good, average, below average and failure) and to rate their success on a scale from five to one in 10 areas of performance. These were: management of government; party leadership; vision for nation; policy legacy; response to governing context; economic management; management of foreign affairs; management of federal-state relations; communication performance; and relationship with the electorate.

Australia’s World War II leader, Labor’s John Curtin, was narrowly judged the nation’s most outstanding prime minister on the core grading question of performance and also rated first when measured against the ten performance indices.

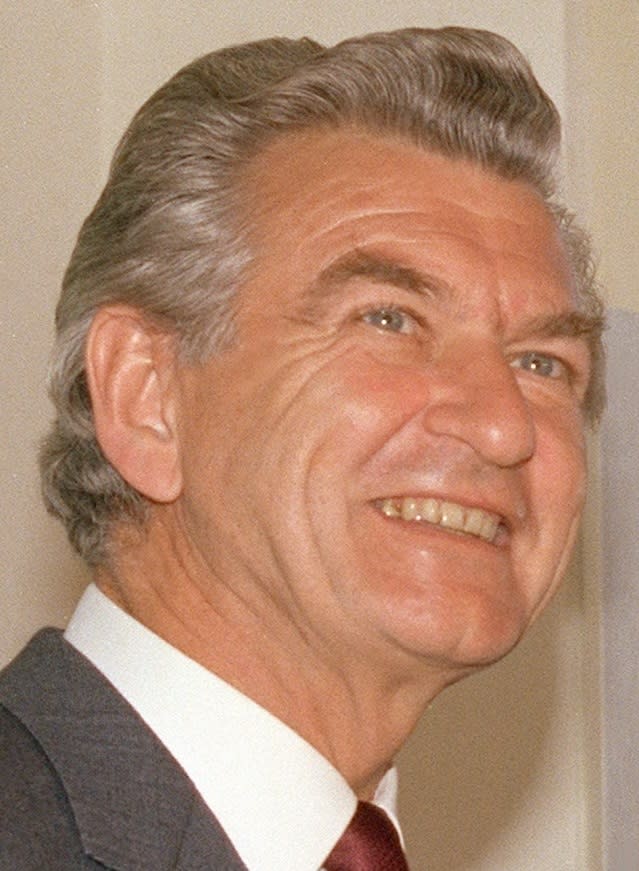

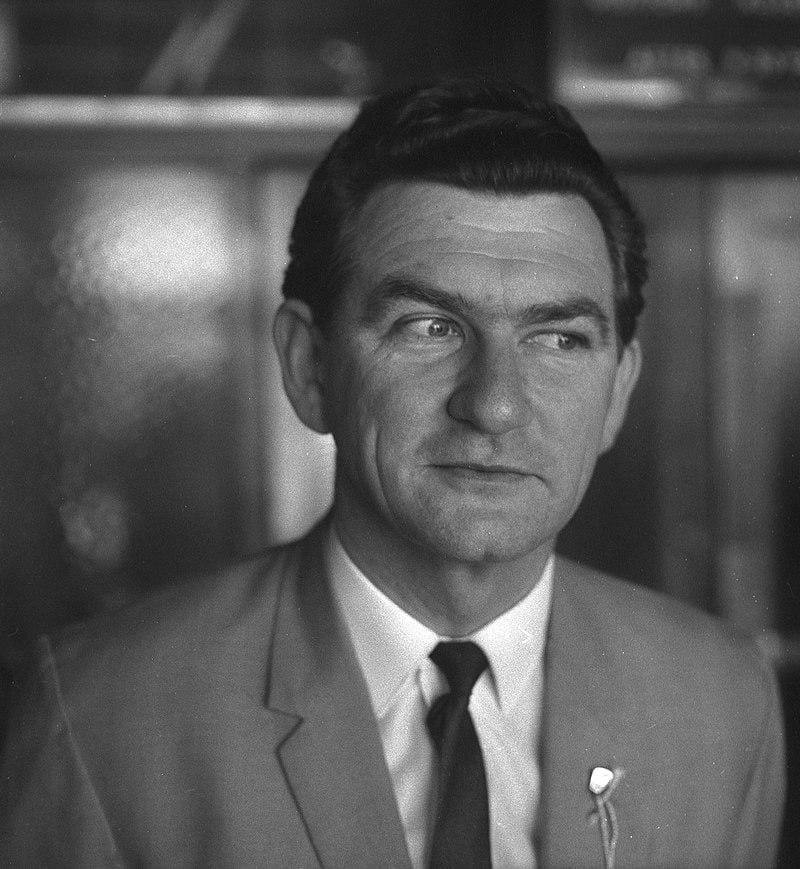

However, in second place, close behind Curtin, was Bob Hawke. I should divulge that in completing both the Monash survey and an earlier rankings exercise initiated by Melbourne’s The Age in 2004 that had asked a 15-member panel of historians and political scientists to rank the 11 ‘modern’ prime ministers from Curtin to then incumbent John Howard, I had opted for Hawke as Australia’s best national leader.

The response to yesterday’s announcement of Hawke’s passing suggests I am not isolated in this assessment. Hawke has been widely lauded over the past 24-hours as the nation’s finest modern prime minister. What made Hawke so successful in a role that has confounded many of its recent occupants?

As is so often the case with leadership, it was an alchemy of circumstances and individual capacity. Hawke came to office in March 1983 following a decade of policy uncertainty and upheaval. The Keynesian mixed economy model that’s been a guiding star for policymakers since the end of World War II had begun to exhaust its utility by the early 1970s, creating in its wake stagflation (a combination of low economic growth and rising unemployment and inflation).

Hawke, supported by an unusually talented crop of ministers and in particular his brilliant treasurer, Paul Keating, would seize the moment to implement a new market-based policy regime that would modernise and internationalise the Australian economy. It became the orthodoxy of Australian policymaking for the next quarter of a century. That transformative agenda was introduced by the Hawke government, however, with a distinctive Labor twist — in partnership with the trade union movement and with social wage trade-offs (for example, Medicare).

Hawke would also profit from long-run institutional developments that had strengthened the hand of the prime minister in coordinating government and shaping policy direction.

For all his knockabout larrikin image, Hawke was highly disciplined, hardworking and attentive to proper process.

Particularly notable here were the expansion and increased policy expertise of the Commonwealth Public Service, headed by a powerful Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and the rise since the early 1970s of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO).

Under Hawke these developments were built upon, especially through further growth of the PMO. Yet Hawke was canny enough to avoid the pitfalls in the running of the PMO that would occur under some of his successors. He staffed his private office with a mixture of experienced officials, policy wonks and hardened political operators, who provided him with fearless and bracing counsel where necessary.

Hawke also brought distinctive skills to the role of prime minister. Though he had entered parliament less than three years before his 1983 election to government (one reason he was never an especially strong parliamentary performer), he had an established close rapport with the Australian people from his days as a leader of the trade union movement.

Hawke was a prodigiously talented communicator on television, which had emerged by the 1970s as the dominant means of political messaging. He had a rare, perhaps unparalleled, knack of projecting authenticity down the barrel of a television camera. His immense personal popularity, reflected in stratospheric leadership ratings during the early years of his prime ministership, supplied a vital source of political capital that his government expended in pushing through a reform agenda that was often contentious, including within the wider Labor Party.

Another of Hawke’s great attributes was his ability to manage his government.

For all his knockabout larrikin image, Hawke was highly disciplined, hardworking and attentive to proper process. He had a methodical approach to paperwork, consulted widely, and listened keenly.

Hawke dispersed rather than hogged power. He preferred to establish general priorities and directions, and then allow ministers the latitude to design and pursue initiatives.

It was in handling cabinet that Hawke especially excelled. His management style has been compared to that of a chairman of the board. He tolerated long disquisitions from passionate ministers, but was astute in summing up the thrust of debate in a way that suited his needs. He was unafraid to grant dissenting ministers the opportunity to state their views in cabinet because he was effective in establishing and maintaining esprit de corp and discipline. If he had to let a minister down, he would strive to do so as gently as possible.

That Hawke set a gold standard in cabinet management has been widely acknowledged. His successors have tried to match his example but seldom have they succeeded. At least in part this is because his mastery of cabinet were products of instinct and prior experience as a negotiator and conciliator in the trade union movement. Yet his willingness to delegate authority — to be an enabling leader — also sprang out of an unassailable sense of self.

A notorious psychological profile published near the end of his prime ministership excoriated Hawke as an overweening narcissist. Anyone who has ever looked at a photograph of Hawke will see that he did indeed radiate self-love. Yet, arguably, it was because his sense of self was so secure that we find the answer to why he could so confidently share power and allow others to flourish in government beside him.

And it was that extraordinarily positive, expansive persona and gift for orchestrating distributed leadership that perhaps, above all else, made Hawke such a successful prime minister and saw him leave a profound imprint on Australia.