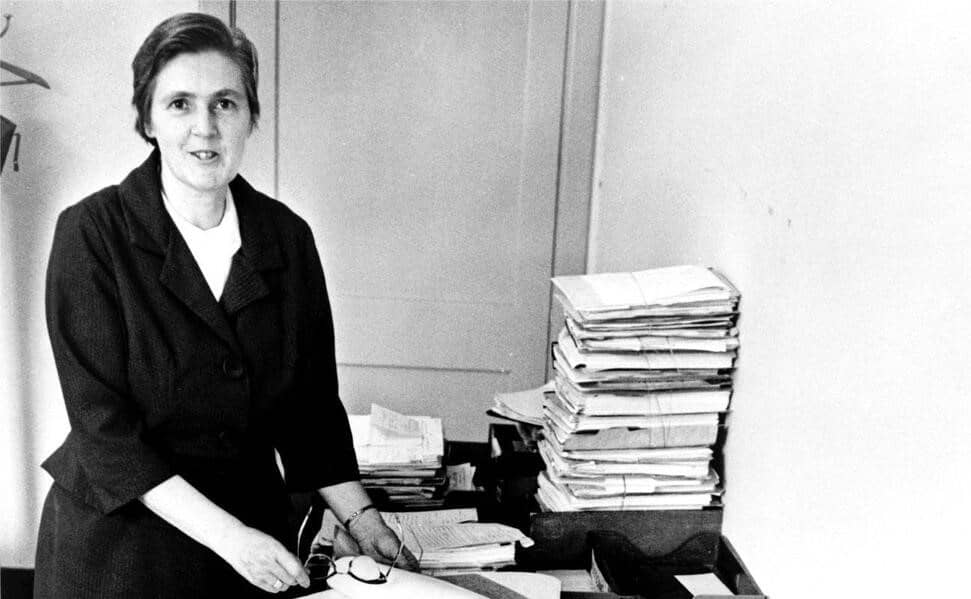

Dr Frances Kelsey began work at the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 1 August, 1960. Her responsibilities were based on the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act:

“New drugs were cleared for marketing on the basis of safety claims alone. The agency had 60 days to reach a decision … Failure to communicate by the 60th day would result in automatic approval.”

Just six weeks into her job, on 12 September, 1960, Dr Kelsey began reviewing a drug marketed in 46 countries since 1957 as a safe, non-addictive sedative. She immediately noticed “deficiencies in all areas” that escalated upon further exploration in the ensuing months.

Under Dr Kelsey’s watch, Thalidomide never gained FDA approval. Her decision prevented scores of birth defects, and in 1962 she received the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. Combined with Dr Kelsey’s tenacity, the 1938 Act proved sufficient in the US, but tragically, lack of even weak regulations elsewhere led to approximately 10,000 disabling birth defects worldwide.

Almost all features of modern drug regulation can be sheeted home to Thalidomide – drug registration; animal testing; written consent for research trial participants; data not only on safety but also effectiveness; and reporting of adverse effects. Few Australians know these details, but many can visualise the deformed or absent limbs that were Thalidomide’s hallmark.

This underlines an often-overlooked point – medical regulators (like sporting umpires) are judged not by their numerous and silent successes, but by their few mistakes.

Consider Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration’s monumental scope. It regulates prescription medicines, vaccines, vitamins and minerals; sunscreen; therapeutic devices (pacemakers, artificial hips); and blood or blood products. Yet medical regulatory failures in Australia are mercifully rare.

The perception that TGA approvals are in any way rushed would give ammunition to vaccine-deniers and conspiracy theorists who have already demonstrated their willingness to spread false information and disrupt the national vaccine rollout.

But they are not zero. Australians have experienced serious, sometimes lifelong health impacts from devices including breast implants, hip prostheses, and transvaginal mesh.

Like Thalidomide, these failures have led to strengthening of regulatory practice. In response to the 2018 Senate inquiry into transvaginal mesh, the Australian government’s 13 recommendations included mandatory reporting of adverse events, creation of registries for high-risk devices, and importantly, use of transvaginal mesh only as a last resort.

It’s cold comfort for those left devastated by medical regulatory failures that they are rare. But they’re rare because the TGA is risk-averse.

It’s almost comically hypocritical to argue that the TGA needs to “loosen up” in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. National and state leaders have spent the past 18 months locking borders and imposing numerous other restrictions. In the main these are sound, evidence-based public health measures, but they’re also driven by near-naked political risk mitigation.

This has resulted in almost unfathomable outcomes such as denying people the chance to return from countries where COVID is so rampant they risk their health by staying; or stopping people saying goodbye to dying relatives. Governments and health authorities have been risk-averse in the extreme – why on Earth would medical regulators not be the same?

Consider also the consequences of rushed decisions on COVID vaccines on vaccine confidence. The mixed messaging over suitability of the AstraZeneca vaccine for adults under 60 resulted in public disagreements between state-based health authorities and the Prime Minister.

The perception that TGA approvals are in any way rushed would give ammunition to vaccine-deniers and conspiracy theorists who have already demonstrated their willingness to spread false information and disrupt the national vaccine rollout.

If you’re sitting on the fence about the question of whether the TGA is too conservative, read a few pages of the transvaginal mesh Senate report, or reflect on the Thalidomide story. Then ask yourself this: If you could choose anyone, who would you pick to open the approval file of the next medicine or device that goes into your body?

My pick would be Dr Frances Kelsey. She died in 2015 leaving a legacy for which we should all be very thankful.