The Australian government’s recent rapid shift in COVID-19 policy from suppression to ‘living with the virus’ has been a failure on many levels. This is most evident with the emphasis on relying on rapid antigen tests (RATs) to self-diagnose for viral infection.

While the notion of self-testing — for pregnancy, genetic-based health risk, and recently epilepsy — is now familiar to, and widely accepted by, the community, the deployment of RATs presents a unique set of challenges and problems. The short-term and longer-term personal and social consequences of the recent shift in testing policy are likely to be profound.

Making individuals responsible for testing (or ‘home-testing’) with RATs, with little knowledge of when best and how to test, and the limitations of testing, leaves much scope for interpretation and error.

This is part of a broader trend in healthcare that has recently accelerated, especially with the appearance of the Omicron variant. Governments in many countries—including Singapore, the UK, the US, and now Australia—have adopted a similar approach to tackling the virus.

A major danger of any medical intervention is offering people false hope. I have written extensively about the role of hope in relation to COVID-19, and more generally, pointing to the dangers of unwarranted confidence in technologies to solve complex problems.

Our recent sociological research on testing in Australian healthcare, funded by the Australian Research Council, reveals that, despite its promise, medical testing rarely provides patients and clinicians with certainty and the assurances they seek.

To the contrary: testing often creates uncertainty and anxiety which often leads to further tests. The phenomenon of the testing cascade is well known and a factor contributing to burgeoning healthcare costs. The health professionals and health policymakers whom we interviewed in our study acknowledged these uncertainties and anxieties, noting that testing was often a way of allaying their own and their patients’ anxieties rather than providing a definitive diagnosis. Not surprisingly, patients’ experiences of testing are often ambivalent.

These observed uncertainties and anxieties are likely to be heightened by the growing reliance on RATs. High hopes are attached to RATs, which are evidently shared by many people who, in seeking to ‘do the right thing’ as responsible citizens, have sought to purchase and self-administer tests.

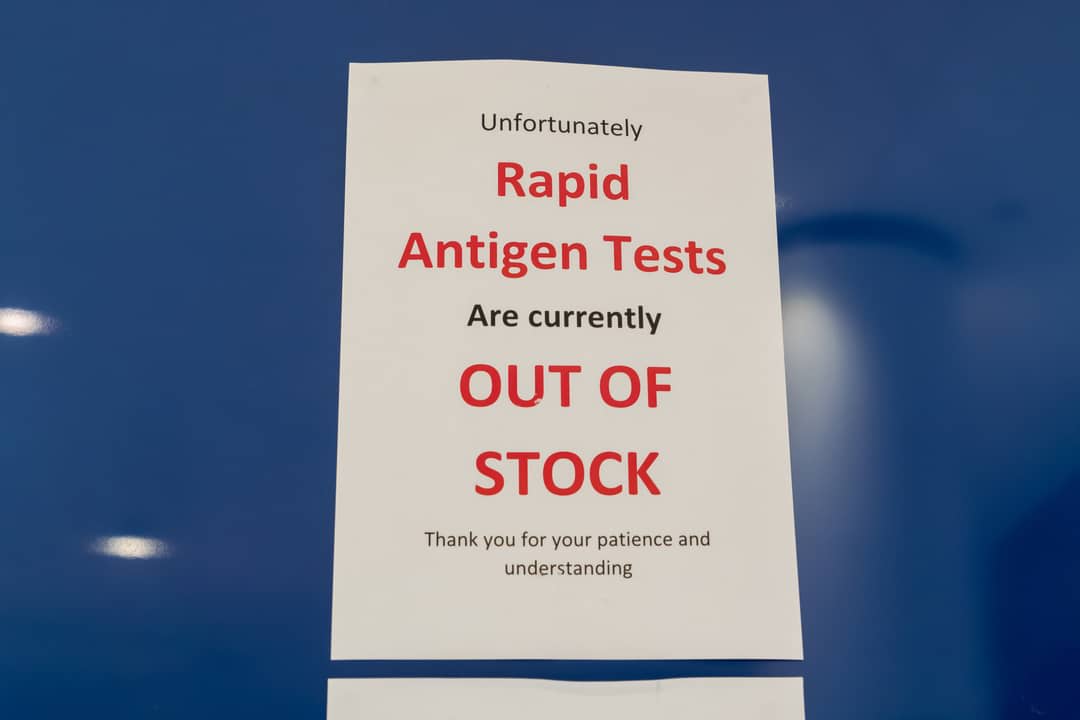

The search for tests is also undoubtedly underpinned by fear of infection. Yet, the market for RATs operates much like other markets, with the rapidly increasing demand affecting supply and price. Consumers quickly encountered restricted supplies, and price gouging. This didn’t need to be the case. In some other countries, such as the UK, tests have been given to people for free or have involved price caps.

Creating a market for RATs was bound to create problems, including the creation of newer unregulated markets to meet demand, and the reinforcement of inequalities.

In the US, there have been reports of new questionable COVID-tests and pop-up testing sites.

In Australia, desperate pharmacies have chartered flights from China to deliver RATs. Meanwhile, ordinary citizens have been compelled to explore innovative ways of finding tests for themselves and others, including creating websites such as ‘Find a RAT’.

Nine in 10 pharmacists surveyed by Professional Pharmacists Australia said they could not source rapid antigen tests (RATs) and one third could not even get enough vaccines to deliver booster doses.https://t.co/IjxZaIKrTC— Professional Pharmacists Australia (@Prof_Pharm_Aust) January 19, 2022

The supply squeeze has been complicated by the actions of the federal government, which is in election mode, and big businesses purportedly diverting supplies for their own needs. Many citizens, including those who are required to show evidence of their test results to enable them to work, are unable to afford to pay for tests, especially given their escalating costs.

Questions raised about sensitivity of RATs

Now that RATs are in the market, questions have been raised about the sensitivity of tests and whether saliva or nasal samples are best. (Recent research suggests that saliva-based tests may detect infection days earlier than nasal swabs.) This will lead to confusion and a potential loss of public confidence in the reliability of tests.

RATs were never promised to be the ‘gold standard’ tests, which are the PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) tests. RATs were meant to be the readily available and easy-to-use alternatives when it became evident (in Australia just before Christmas) that the PCR test regime had failed. Queues of people lining up for hours, and then waiting often for many days for results which were then deemed useless, provided the context for the rapid shift in testing policy.

Read more COVID-19: Will 2022 be the year we get the pandemic under control?

Worryingly, in the US, recent reports of false negatives with RATs have emerged. For example, in that country there is a recently reported case of an individual receiving six negative results from RATs before the Christmas holiday period and subsequently found to be positive via a more sensitive, lab-based PCR test.

In Australia, currently 22 RATs have been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration. They provide results within minutes and don’t need to be analysed in a lab as do PCR tests which can take a number of days. But the sensitivity of RATs varies considerably: from ‘acceptable’ to ‘very high’ sensitivity. That is, some tests are likely to produce results that are less reliable than other tests, producing more false positives or false negatives. However, it is doubtful that many members of the public would be aware of this fact.

A way forward

How should authorities address the disastrous situation that has been created?

It is difficult to reverse policy decisions and funding investments once made, since they tend to become ‘locked in’, creating ‘path dependence’ where earlier decisions affect later ones. Inconsistency and frequent changes of policy undermine public confidence and trust in tests and testing. The Australian federal government was at first reluctant to adopt RATs, despite advice that it should order tests, as were a number of state government and health authorities.

Now that we have a changed testing strategy, it is crucial that authorities acknowledge and communicate to the public the limitations and implications of RATs, and make the more reliable tests readily accessible to everyone.

'Unrealistic, unfair demands have been placed on individuals to procure, interpret and act on tests, including reporting the results.'

In its recent attempt to ease the shortage of tests, the federal government has urged states to clarify workplace health and safety rules so that daily testing is limited to the most vulnerable industries. But this is shifting the blame onto the states, and doesn’t clarify businesses’ confusion about their testing obligations. It also doesn’t address the aforementioned uncertainties concerning the reliability of RATs.

A failure to undertake action of the kind I suggest will lead to a further erosion of trust and likely create untold social damage, including conflict in workplaces and social settings which demand evidence of a negative test as a condition of entry.

This conflict is always evident in workplaces and other venues where results from RATs are required—especially when the costs are shouldered by the individual. Unions have called upon employers to cover the costs of RATs and have threatened industrial action if they do not. This latest call is part of a raft of demands that unions are making to protect workers’ health, including better ventilation and access to better quality masks.

Unrealistic, unfair demands have been placed on individuals to procure, interpret and act on tests, including reporting the results.

Leaving it to individuals to procure RATs (except for certain eligible citizens) and then to interpret and act on them denies the complexities involved and the personal, economic and social implications, including discrimination. The current policy on RATs is a disaster by any measure. The government should own up to its policy failure and try to improve the situation as soon as possible.