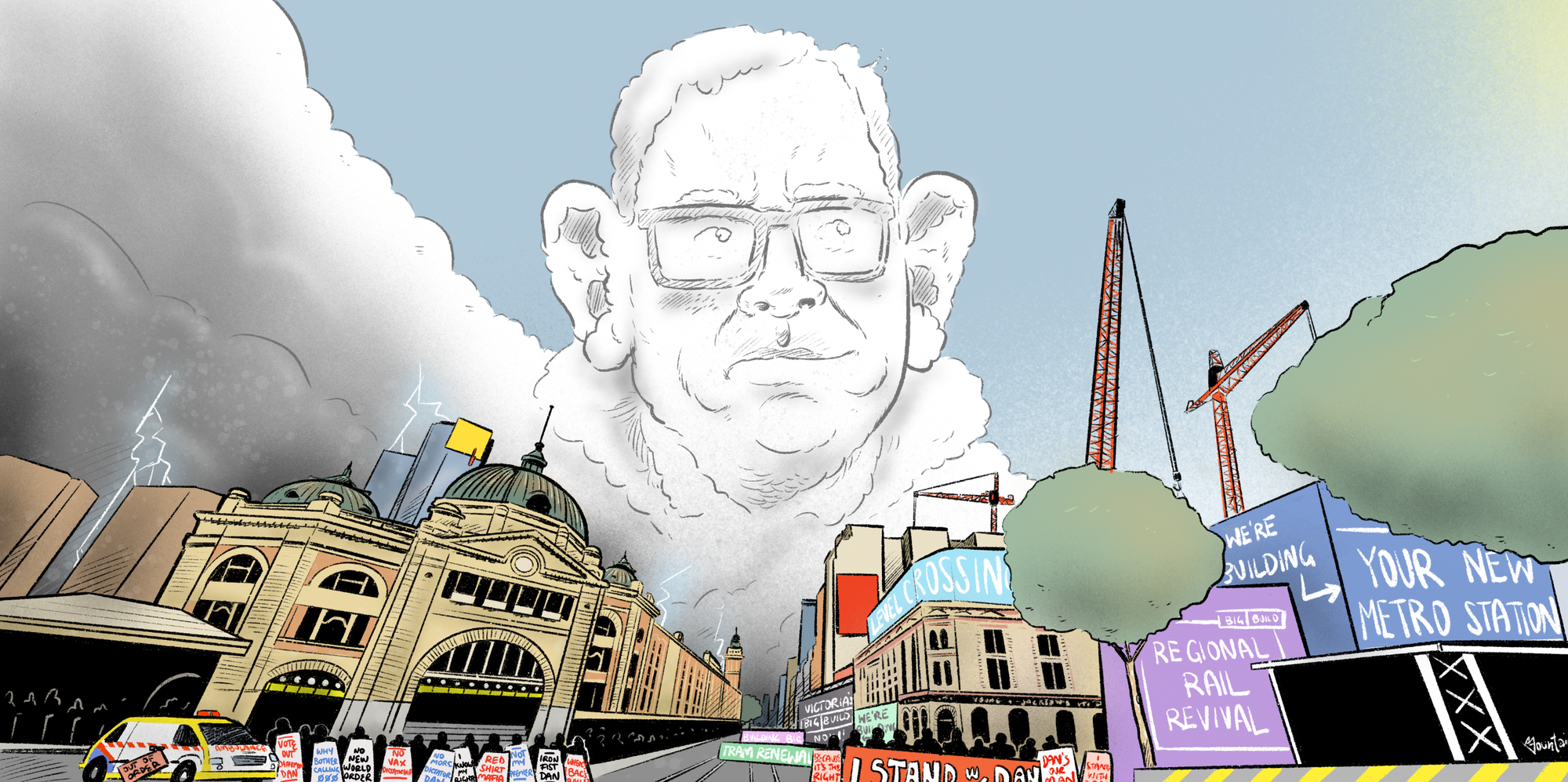

“Dan”, they call him. The headlines in Victoria’s tabloid Herald Sun have ceased referring to the state’s premier by his second name – Dan is sufficient. It’s symbolic of how much Daniel Andrews bestrides the state political scene.

Nobody requires a reminder of who he is, and few don’t have a strong opinion about him. He’s a local colossus, a leader who dominates the state unlike any other since the time of Jeffrey Kennett in the 1990s – another premier who came to be known by his first name only – Jeff.

Like Kennett did, Andrews also enjoys high recognition beyond Victoria’s borders. In part, this prominence is due to the fact that, first elected in 2014, he’s the senior head of government in the land (Queensland’s Annastacia Palaszczuk is the next-closest). But it’s also because during Victoria’s second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, Andrews’ marathon 120 consecutive days of media briefings gripped audiences across Australia.

‘If you do everything, you will win’

We now have a biography of Andrews (suggestively subtitled “Australia’s most powerful premier”) by The Age journalist Sumeyya Ilanbey, which fleshes out his backstory.

He’s the eldest child of Catholic working-class parents, who owned a milk bar in Glenroy in Melbourne’s northern suburbs. When Andrews was at primary school, disaster struck the business, which became a lesson for the young boy in the insecurity of working-class life.

The family relocated to the regional northeastern Victorian town of Wangaratta. There, his father became a delivery driver for a smallgoods firm, and his mother worked as a bank teller.

According to Ilanbey, Andrews’ father instilled in him his “work ethic, and his single-minded determination”, while his mother implanted in him “a social conscience – and a love of politics”.

Like many successful leaders, Andrews showed a precocious interest in politics. A teacher at his Catholic secondary college predicted a future for him in Canberra. While studying at Monash University in the early 1990s, Andrews became involved in the ALP against the backdrop of Kennett’s neoliberal crusade in Victoria.

After graduating, he began work in the electorate office of federal Labor MP Alan Griffin, and from that base emerged as factional secretary of the Socialist Left. At least two characteristics defined the young apparatchik – a meticulous attention to detail, and an utter determination to win.

Despite his relative youth, Andrews launched a successful bid to become assistant secretary of the Victorian ALP. In that position, he went on to play an important role in managing grassroots campaigns that felled Kennett and delivered government to Steve Bracks in late 1999. On his office wall hung a quote from the archetype of hardball politics, former US president Lyndon Johnson: “If you do everything, you will win.”

Andrews’ meteoric rise continued. At 30, he entered the Legislative Assembly, and Bracks immediately appointed him as a parliamentary secretary. He impressed as “a policy wonk who pored over detailed briefing notes”.

When Bracks won a third term in 2006, Andrews was elevated to cabinet. And when John Brumby replaced Bracks in mid-2007, Andrews was assigned the key portfolio of health.

Three years later, after the Brumby government was unexpectedly defeated, Andrews became opposition leader unopposed. Victoria hadn’t experienced a single-term government since the Labor Party split of the 1950s, so his prospects appeared inauspicious.

But plagued by internal divisions, the Coalition government presided over policy stasis and became mired in prolonged industrial disputes with nurses, teachers and paramedics. Running a canny grassroots campaign focused on the bread-and-butter issues of employment, health, education and transport, Labor narrowly won back power in November 2014.

Still an unknown commodity to many Victorians, Andrews was premier at 42.

From the moment he entered office, Andrews was in a hurry to bend Victoria to his will. The inertia of the Coalition’s four years in power, which had exacerbated the strains on the state’s infrastructure and services, and squandered the goodwill of a rapidly expanding population, was a call to arms for action.

But Andrews’ assertiveness was also a function of his strongman leadership type. Fortified by unshakeable inner conviction, he evinced supreme confidence about the direction in which he wanted to take the state.

He’s a premier who not only innately understands how power works, but relishes its exercise – attributes that are surprisingly rare among politicians.

A reformist government

There have been two major strands to the reform agenda his government has pursued during its eight years in office. The first is a gargantuan program of public infrastructure construction, especially in transport, given the public relations moniker “Victoria’s Big Build”.

The signature infrastructure activity of Andrews’ first term of government was the removal of railway level crossings, a politically savvy undertaking that delivered early tangible benefits to commuters.

Alongside that was a suite of massive transport projects. These include the Melbourne metro rail project, an airport rail link, a suburban rail loop, and an array of road extensions and upgrades headed by the West Gate Tunnel and North East Link projects.

It’s not only the scale of the infrastructure building that’s striking, but the way in which the government is financing it.

In its second term, the Andrews administration has accumulated a mountain of public debt, as well as racking up a substantial budget deficit. On the surface an interring of the nostrums of neoliberalism, and an unashamed assertion of big government, that picture is qualified by how much of the investment is being funnelled to a small number of multinational construction corporations, and Labor’s ardour for public private partnerships.

The second key element of Andrews’ reform program has been an adventurous social policy agenda. Capitalising on the fact that the leeway for social activism is greater in Victoria, his government has transformed the state into something of a laboratory for progressive experimentation in Australia.

Its social reform credentials have been burnished through a raft of measures. Examples include:

- establishing the state’s first drug injecting room

- strongly supporting the Safe Schools program

- appointing the Royal Commission into Family Violence

- legislating protection zones around abortion clinics

- decriminalising sex work

- banning LGBTIQ+ conversion practices.

In at least two social policy areas, Victoria has been a trailblazer under Andrews.

After John Howard’s Coalition government overturned the Northern Territory’s short-lived euthanasia laws in 1997, the issue languished throughout Australia. In 2017, however, the Andrews government became a pioneer of voluntary assisted dying laws among the states. It’s a measure now emulated in every state.

Victoria has also been in the vanguard of the nation by embarking on a process for concluding a treaty with the state’s Indigenous communities. The process was launched against the background of the federal Coalition government’s spurning of proposals contained in the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart by Indigenous Australians for a treaty and truth-telling commission.

Since 2019, an elected First Peoples’ Assembly has been in place in Victoria. It has had responsibility for creating the framework for treaty negotiations.

In 2021, a “truth telling” commission (the Yoorrook Justice Commission) was set up as part of the treaty process. This body is inquiring into injustices committed against First Nations peoples dating back to the earliest days of colonisation.

It may also investigate the potential for reparations being paid to Indigenous Victorians to make amends for historical wrongs.

Most recently, in another national first, legislation was passed to establish an Indigenous Treaty Authority.

To be composed entirely of First Nations representatives, the authority is to act as an independent umpire facilitating treaty negotiations and resolving disputes between traditional owner groups and the state government.

The body is autonomous from government – it’s not required to report to a minister, and its funding is insulated from the usual political cycles. Its creation paves the way for formal treaty negotiations to begin in 2023.

No shortage of scandals

The combination of progressive boldness, political effectiveness and the Premier’s forceful leadership style has made Andrews an arch enemy of conservatives. The chasing after him by News Corp’s Herald Sun and commentators on Sky News borders on the obsessional. The impotence of their attacks on him to date has only fuelled their rage.

The loathing is mutual. To opponents, Andrews plays the political hard man. Typical of the strong leader, he gives little truck to alternative viewpoints, and doesn’t disguise his contempt for his accusers.

One of his methods is to freeze out critics – for example, boycotting Melbourne’s top-rating morning talkback radio program, and thumbing his nose at the Herald Sun.

This tactic sits within a larger innovative communications strategy of bypassing the mainstream media in favour of unfiltered engagement with the public through social media.

Andrews is a prolific user of Twitter, and especially Facebook, more active in the space than any other head of government in Australia. His one million followers on Facebook dwarfs that of his leadership counterparts, the Prime Minister included.

Andrews is a formidable communicator, a master of conversing with the electorate through uncluttered and persuasive messaging.

Brazenly crashing through controversies is a disquieting trademark of Andrews’ leadership. His government has been embroiled in no shortage of scandals during its eight years in power.

In its first term, it was dogged by the so-called “red shirts” affair, which involved the misuse of public funds by the Labor Party during the 2014 election campaign. When the episode first came to light, Andrews’ first line of defence was to dismiss the allegations and then “dig in his heels”.

The premier’s habit of doubling-down when his government is under pressure is accompanied, Illanbey explains, by a pattern of calculated evasiveness towards scrutiny.

In Labor’s second term, the media exposed more skulduggery in the ALP. A resulting joint inquiry by the Independent Broad-Based Anti-Corruption Commission (IBAC) and Ombudsman reported a sordid tale of industrial-scale branch stacking, and further misuse of public resources.

This time there was no place to hide. In an uncharacteristic moment, the Premier apologised for his party’s behaviour.

These events have tainted Andrews’ record as Labor leader. Though he moved speedily against ministers implicated in the second of these episodes, and seized on the moment to successfully press Labor’s national executive to appoint administrators to run the Victorian branch as an instrument to overhaul its practices, the impression was that he had been too long complacent about the party’s excesses.

Centralisation of authority has been a troublesome recurring theme of government practices at both federal and state level over recent decades. Under Andrews, that phenomenon is pronounced.

Power is heavily concentrated in his hands, those of a small cabal of ministers, and in his private office. The latter is some four times greater in size than it was before he became premier, its activities undermining accountability.

Illanbey paints a damning picture of governance in Victoria on Andrews’ watch:

The bureaucrats have been politicised and have become an extension of the premier’s political staffers; the 21 ministers who are collectively responsible for making decisions are sidelined in favour of the Gang of Five; the staffers in the premier’s private office and a select few departmental secretaries have greater power and access to Andrews than most ministers and backbenchers. Freedom-of-information requests are routinely blocked; hundreds of departmental documents are routinely dumped on one day in the Victorian parliament, making it all but impossible for the public, journalists and non-government MPs to trawl through them effectively. Extensive cabinet meeting minutes are not taken, in order to limit the political damage in the event of a decision being leaked. Political staffers and the Department of Premier and Cabinet routinely draft policy that is within the remit of other ministers, and they micro-manage the work of specialised departments such as health, transport and education. Often, the first that backbenchers and even junior ministers hear of a policy is when it’s announced at a press conference.

Alongside the tight control exercised by the Premier is a ruthlessness towards those in his own ranks who cross him, or who he regards as becoming a liability to his leadership.

Ministers have been unceremoniously cut adrift, while others who fall out of favour are notoriously put in the “freezer” by Andrews. Those who have suffered his wrath say his loyalty is to him alone.

The polarising Premier and the pandemic

The greatest crisis of Andrews’ tenure has, of course, been the COVID-19 pandemic, which has dominated Labor’s second term in office. Victoria not only experienced the worst death toll of any Australian state, but Melbourne earned the unenviable record of being one of the world’s most locked-down cities.

His handling of the pandemic had a polarising effect. The government’s bungled hotel quarantine system, a product of a disastrous breakdown in bureaucratic and political lines of authority, unleashed the second wave of the pandemic.

Andrews reacted in the only way he knows how – by further asserting his control.

Against the background of his extraordinary endurance feat of four months of daily media briefings, a fierce online battle raged. On the one hand, there was a “I Stand by Dan” solidarity campaign with overtones of the leader as saviour. On the other hand, a melange of self-styled libertarian activists and conservative media rallied around the trope “Dictator Dan”.

They not only held him personally culpable for the second wave, but condemned his response as overbearing and dangerously untrammelled. By the latter months of 2021, as the state endured a sixth lockdown, normally temperate Victoria had developed a febrile anti-lockdown movement dotted with conspiracy theorists.

Their hatred of Andrews was extreme. Yet, amid the polarisation, the majority of the public stood firmly by the Premier, endorsing his management of the pandemic. They seemed to admire his resoluteness, and accepted that the lockdowns, however oppressive, were a necessary evil to protect the community.

A third term?

Andrews stands on the verge this month of winning a third term in office. The result is unlikely to replicate the “Danslide” of 2018, with Labor’s primary vote set to be significantly down.

In a repeat of what occurred at May’s federal election, support for minor parties and independents will spike, announcing this as the new norm of Australian politics.

Nevertheless, the opinion polls show Labor is still strongly placed to retain a majority. The government’s enduring electoral appeal is arguably remarkable. After all, this is an eight-year-old administration prematurely aged by spending much of this term in crisis mode managing the pandemic.

The government continues to be shadowed by unwelcome revelations.

The latest is about an investigation by IBAC into multimillion-dollar grants to an ALP-aligned health union prior to the 2018 election, with media reports that bureaucratic advice was ignored, and that the Premier and his private office trampled due process.

And under Labor’s stewardship, the health system is ailing, and there’s a burgeoning list of infrastructure project delays and budget overruns.

What then explains the government’s resilience? To seething right-wing warriors, the answer lies in Victorians succumbing to a form of Stockholm syndrome, or even more sinister plotlines in which Andrews is feverishly imagined as a kind of local version of Kim Jong-un, a supreme leader grown democratically untouchable.

The truth is far less fanciful.

First, the ongoing strength of support for Labor is consistent with the patterns of the state’s electoral politics stretching back to the early 1980s. Over the past four decades, the ALP has dominated elections in Victoria at both state and federal level. It’s ruled over Spring Street for three-quarters of that era.

Labor has, in short, become the natural party of government of the state. Faced with the reality of the left-of-centre political ascendancy in Victoria, conservatives no less than John Howard have taken to ruefully describing the state as the “Massachusetts of Australia”.

As I have argued previously, Labor is now the closest thing there is to a custodian of the progressive liberal reformist tradition in Victorian politics, an impulse that originated in colonial times, and whose bearers included such luminaries as Alfred Deakin.

In that way, Labor better fits the philosophical grain of Victoria than does its chief political opponent.

Second, and by extension, the Andrews government has benefitted from the haplessness of the Liberal Party opposition.

Epitomised by the tin-ear law-and-order campaign they ran at the 2018 election that helped deliver Labor its landslide victory, the Liberals have been too often out of tune with the sensibility of Victorians.

Short of talent, infiltrated by conservative religious elements, and prone to infighting, the party has struggled to establish itself as a credible alternative government. Its lack of appeal to younger voters is nothing short of a crisis.

Admittedly, the Liberal Party has done a better job in this campaign by hewing towards the centre and focusing on mainstream concerns, but most polling suggests its primary vote is anchored at a level at which it’s not a serious competitor for office.

Third, while the electorate might not agree with all aspects of Labor’s activism, it’s won continuing credit for being a government that does things. And it counts that physical reminders of that busyness are ubiquitous throughout the state.

Fourth is approval of Andrews himself. Misgivings about the premier have undoubtedly increased as his style of governing has grown more conspicuously heavy-handed. The dictator epithet, however hyperbolic, has obtained currency in the community; it’s a refrain that frequently surfaces in polling survey responses.

Even so, those same opinion polls shows support for Andrews’ leadership has stayed robust. He’s perceived as energetic, decisive, smart and capable.

The public also seems to appreciate his ambition for the state to be a national leader. An illustration of that continuing ambition is Labor’s announcement in this election campaign of increased carbon emission reduction and renewable energy targets that puts Victoria out in front of other jurisdictions.

Andrews has vowed that if he wins the 26 November election, he’ll stay on for another full term. This would mean he would not only be premier for 12 years, but leader of the Labor Party for 16 years. This stretches credulity, and neither the public nor his colleagues would wish for that longevity.

Victoria would indeed benefit before long from a disturbance of the power relations centred on Andrews. The strong likelihood is that he’ll relinquish the premiership no later than the middle of the next term. He’ll hand over to his chosen successor, Jacinta Allan, in a final act of control.

In this scenario, Andrews will depart office as the longest-serving Labor premier in the history of Victoria, eclipsing the record of John Cain junior. Like Cain, he’ll leave a mighty imprint on the state, having radically remade its physical infrastructure, and modernised its social fabric.

He’s emphatically demonstrated the enduring capacity of a state government in Australia to powerfully shape the lives of its citizens.

The legacy of Andrews’ governance method, on the other hand, will be more troubling. Perhaps above all else, he’ll be remembered for being a political force of nature.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.