Pregnant women are bombarded with advice about what’s safe and what’s not. They’re told what they should or shouldn’t eat, whether or not to drink coffee or alcohol, and how much exercise is safe.

These aspects of pregnancy have been well-researched, providing an evidence-based, albeit ever-changing, guide to the risks involved.

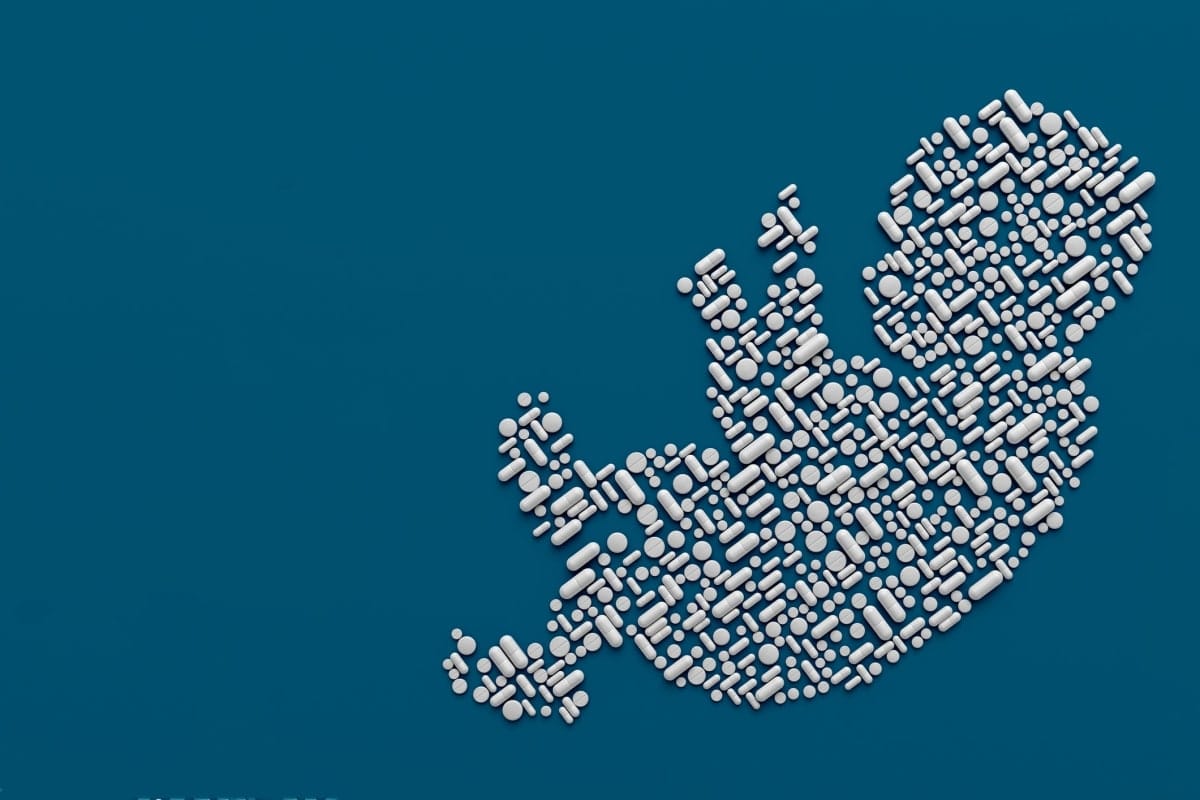

But for some reason, the impact on the foetus of drugs taken in pregnancy has never received the attention it needs.

The thalidomide legacy

The thalidomide crisis of the late 1950s, which saw babies born with severe limb deformities after their mothers took the drug for morning sickness, underlined the potential dangers.

Thalidomide was never approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the US, although it was imported and prescribed “off-label” (that is, on the advice of a doctor). There were some cases of limb deformities, but not as many in Europe and Australia, where the drug was approved for treatment of “morning sickness” in pregnancy.

It had been tested in non-pregnant animals and adults, and was reported to be extremely safe. It took some time to establish the link between limb deformities and thalidomide taken early in pregnancy.

This did lead to more stringent testing requirements and reporting on clinical cases when pregnant women had taken drugs, but the focus was on congenital defects from drug exposure early in pregnancy, and it’s only relatively recently that there’s been serious discussion about the need for clinical trials in pregnant women.

These discussions are summarised here.

More clinical trials needed

However, it’s unlikely that clinical trials will be conducted for many, if any, of the more than 1200 drugs that have been, or still are, prescribed to pregnant women.

Clinicians have to rely on experience and information from various databases. The problem for the clinician and their pregnant patients was clearly explained by the US obstetrician Sumner Yaffe in 1966:

“The administration of a drug to a pregnant woman presents a unique problem to the physician; not only must he consider maternal pharmacologic mechanisms, but he [sic] must also be aware of the foetus as a potential recipient of the drug.”

Yaffe collaborated with two colleagues to produce a compendium (Pregnancy and Lactation) of published information on drugs prescribed. It’s been updated regularly, and the latest edition (Briggs, Freeman, Towers and Forinash, 2022), produced 12 years after Yaffe’s death, was published last year.

Their most reassuring recommendation for drug use is that they are “compatible”. Unlike the Australian Medicines Handbook (AMH), Briggs and colleagues don’t suggest that any drug is safe.

AMH recommends that paracetamol is “safe in pregnancy”. The assessment of Briggs, Freeman, Towers and Forinash is that there is a “low risk” with short-term use of paracetamol (acetaminophen in the US), and “risk” with long-term use.

More recent evidence (some provided from our studies) reinforces these conclusions. Australia’s Therapeutic Drugs Administration (TGA) Prescribing Medicines in Pregnancy Database rates paracetamol Category A:

“Drugs taken by a large number of pregnant women without any proven increase in the frequency of malformations or other direct or indirect harmful effects on the foetus have been observed, which contrast with the evidence summarised by Briggs et al., indicating some degree of risk.”

Informed decisions still difficult

The recommendations from Briggs et al are certainly better than no information, but many health professionals and pregnant women are left with difficulty in making an informed decision about whether to continue or initiate what could be crucial medication.

This includes drugs for conditions such as epilepsy, depression, psychosis or schizophrenia. Discontinuation of the drugs may pose a greater risk to both mother and foetus than continuing treatment.

Clinicians try to deal with this by reducing the dose of a drug and/or adding a second drug to maintain an adequate clinical response. An example is valproate and lamotrigine, which are used for seizure control in epilepsy.

Paracetamol is taken by up to 80% of pregnant women in some populations and any effects are likely to occur in female and male offspring.

A major problem with paracetamol is that much of it is taken by self-medication, so there is really a need for public health warnings urging caution during pregnancy.

Given the risks identified by Briggs et al and others to suggest that paracetamol is safe to use in pregnancy is unwarranted.

However, it remains the most appropriate drug for severe pain, although it should only be taken for the shortest possible time.

It’s also a valuable treatment for raised body temperature occurring in infections, as these can precipitate premature birth and injury to the foetus.

Addressing the enormous knowledge gap

Only a small research movement is addressing this enormous gap in knowledge in this important field, which remains inadequate.

Our research team, previously based at the University of Melbourne and now at Monash University, is one of the few investigating whether drugs enter the foetal brain and/or cause problems.

We also started investigating responses of the placenta (an exchange interface between the mother and the fetus) to short and long-term exposure to some common medications used on their own or in combination with other drugs.

In our latest paper, we investigated olanzapine, which is used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in women of childbearing age.

We’ve also studied paracetamol, valproate, olanzapine, lithium, digoxin, and cimetidine.

Using pregnant and postnatal rats, we’ve found that all of these drugs, except lamotrigine, enter the developing brain to a greater extent than in the adult.

We have some evidence that this is partly explained by less cellular activity of mechanisms that normally limit entry of drugs into the adult brain.

It appears that protection of the foetal brain for these drugs primarily comes from the placenta rather than from the foetal brain itself.

For the drugs studied so far, 30% to 60% were prevented from entry into the fetus from maternal blood illustrating the important role of the placenta.

Drugs and the developing brain

We’re also obtaining evidence on where these drugs are distributed in the developing brain using autoradiography (a technique that allows visualisation of a radioactively-labelled drug).

This is in collaboration with the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO).

To extend this important approach, we’re setting up a collaboration with Dr David Rudd, from the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, to use a new imaging technique ,as it has better resolution and is much quicker to perform (hours rather than months).

Once we’ve established the regional distribution of a drug of interest in the brain, we can then focus our studies of possible brain structure and behavioural changes that may be a consequence of drug exposure during pregnancy.

This in the longer term will provide a basis for clinical studies using imaging and behavioural tests in children whose mothers were prescribed drugs during pregnancy.

From preclinical to human trials

Of course, we need to consider the extent to which results from animal experiments can be transferred to patients.

A substantial amount is known about brain development in humans and rats, which will help in interpreting effects we identify in rat brains. At least some of the mechanisms known to limit drug entry into the brain are similar in humans and rats.

It will be possible to obtain confirmatory evidence from umbilical cord blood and placental samples from mothers who have taken drugs during pregnancy. These are non-invasive studies, but of course require appropriate ethical approval.

In relation to brain development, we have access to a large collection of human foetal brains that were collected by our colleague, Professor Møllgård, at the University of Copenhagen.

These were collected from therapeutic abortions with the approval of the local ethics committee. We’ve been collaborating with Professor Møllgård since the early 1970s.

This material will allow us to make specific comparisons between the development of rat and human brains. Where there are records of drugs taken during pregnancy, this will allow more direct comparison with the rat experiments.

No drug is safe in pregnancy

We would argue that no drug is safe, and there’s increasing evidence from studies in pregnant women that some may have deleterious effects in the offspring.

But this is mainly from clinical observation or epidemiological studies that at best can only establish an association. There are very few animal studies, apart from ours, being conducted at present.

It’s not all bad news. Some of our research results have been reassuring, and shown that some drug combinations can reduce the amount of a potentially harmful therapeutic reaching the foetus.

For example, our latest study showed that doses in the clinical range of lamotrigine, valproate and paracetamol each reduced the entry of olanzapine into the rat foetus to about half of that of olanzapine alone.

Entry into the mother’s brain was not affected; thus, there’s the potential to retain clinical effectiveness in the mother, but reduce fetal exposure.

On the other hand, placental transfer of olanzapine was increased by cimetidine or digoxin, potentially increasing the risk to the fetus. This indicates these combinations should be used with caution.

Not just a ‘women’ problem

There’s growing recognition that more research is needed in this field, so that more accurate advice can be provided.

This is a problem not just for women who are or could become pregnant; male offspring could also be affected.

Every researcher believes their field is the most important and should be supported. Given the magnitude of the problem and the lack of research and funding support in this case, this might just be true.

This article was co-authored by Professor Katarzyna Dziegielewska, an adjunct professor from Monash University.