The awful new sickness arrives suddenly with rumours and half-truths as to its origin.

It’s highly contagious and deadly. Medical systems are quickly stretched. There’s no vaccine and no consensus about how to contain it – and who should do the containing.

Some people wear masks, some refuse. Travellers are quarantined, the populace locked down. Businesses shut and the economy goes south. Borders shut. Governments argue with each other. The death toll rises.

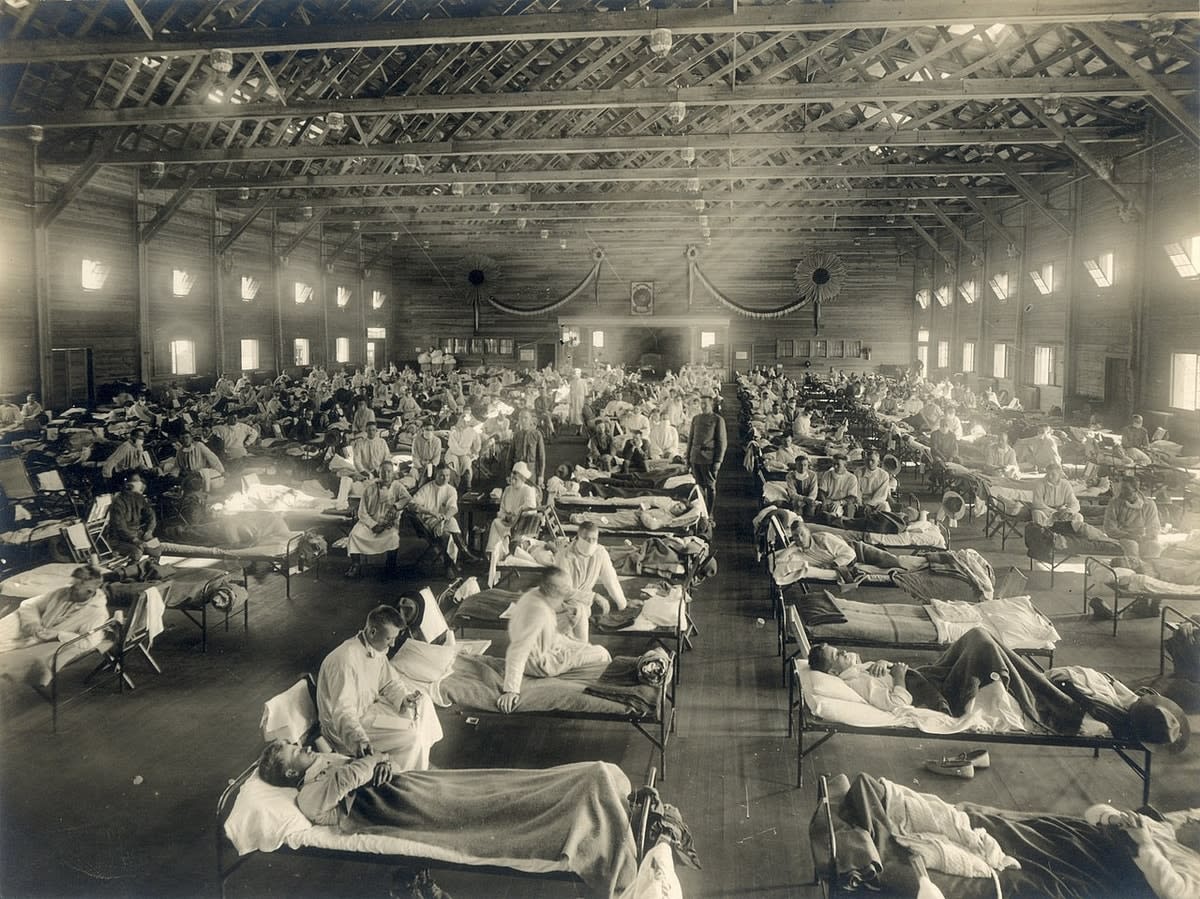

In our year of COVID-19 this should all sound familiar, but in fact it’s a description of events 100 years ago during the Spanish Flu, the worst pandemic in history.

It hit Australia hard, killing 15,000 here and 50 million worldwide, yet has been called “The Forgotten Flu”.

So what happens to our experiences of COVID-19? What was it actually like at the frontline in hospital intensive care units? What does it hold for the future of hospital care, and the teaching of that care? Also, what can we take from it as a society – what did it mean?

Read more: What can we learn about chronic disease from COVID-19?

Rose Jaspers of Monash University Nursing and Midwifery is a member of the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce, a brains trust of Australian experts providing advice on the pandemic.

She’s also a board member of the Australian College of Critical Care Nursing, and says vaccines starting to roll out mean “the citizens of this planet have dodged a bullet”.

“There is a vaccine, and indications are that it will be available to all. Admittedly, equity in the population achieving vaccination will be dependent upon governments and benefactors in some bases … Had we [in Australia] not flattened the curve, the cost to the economy, population wellbeing and general health would have been comparable [to other countries] or greater.”

When it first broke, however, in increasingly urgent news reports from China in January about a strange new “pneumonia” spreading in clusters, no one knew quite what to expect, even health professionals.

Jaspers, like all, heard through the media. The devastating Australian bushfires of last summer had not long subsided.

“The virulence was quite evident from the start,” she says. “However, I wasn’t as concerned as I was later as to the severity of the virus.

“Intellectually, at first I thought it could become a pandemic, but in my heart I really didn’t think the disease severity would be so severe. I definitely did not foresee what a political hot potato it would become in some arenas.”

The divisiveness of pandemics

Yet pandemics have always been absolutely divisive.

During the Spanish Flu – in which the lung tissue fell apart, producing a bloody froth from nose and mouth, the victim’s lips often turning blue through cyanosis – New South Wales closed its border with Victoria despite no law allowing that to happen. They were angry that Victoria had, they claimed, not acted quickly enough.

Most states and territories then followed suit with their neighbours. In Sydney, schools, cinemas, churches, public halls and part of the wharves shut. State administrators enforced mask days, but not everyone complied.

During the Spanish Flu ... New South Wales closed its border with Victoria despite no law allowing that to happen.

As retold on the ABC’s Australian Story, an army nurse called Annie Egan was sent to help at a Sydney quarantine station, but contracted Spanish Flu, and was approaching death among the very patients she could have helped.

She asked for a priest to be sent to give her last rites, but when he came he wasn’t let in, leading to a “stand-off” between military guards on one side and Catholic priests and the public on the other.

After she died, the rules were changed to let in priests, as well as doctors and nurses, and Annie Egan was buried with full military honours at North Head.

A century on, COVID-19 is the most divisive yet, befitting a geopolitical context of division – Brexit, Trump, Bolsonaro, #DictatorDan, and the febrile suite of QAnon conspiracies around state-control and freedom.

The response to the virus, in these overheated quarters, turned into a battle of dogma between those who believed lockdowns were for the greater good, and those who did not.

Some of those who did not included the central administrations of the United States, Sweden and the UK, who continue to suffer high death and infection rates. Australia and New Zealand, among others, locked down early and strictly, and are subsequently now all but COVID-free.

The key is in the response

For Monash historian Dr Michael Hau, it’s all about how administrators, or “officials” respond. The difference in responses in 2020 has been stark, from the President of the United States who said it was nothing, to the Premier of Victoria who said it was huge and would only go away if whole cities shut down.

“Look at the United States in 1918,” he says. “There were cases such as in Philadelphia, when the city public health director said it was nothing to worry about. This was during the great second wave of the pandemic. Then in some areas, cases exploded because of this ambiguous response or attempt to play down the threat of the illness. It’s a very interesting parallel with 2020.”

In 1918, World War I was in progress in Europe. This explains why the pandemic was called Spanish Flu even though it wasn’t Spanish.

For many Allied countries – such as Australia – the news of a virulent new illness was censored for two reasons: it might let the enemy know that troops were sick; and it might demoralise the folks back home even more than they already were. So it didn’t go in the news.

Then the King of Spain, Alfonso, caught it. Spain wasn’t in the war, so it did get in the news. Thus, “Spanish Flu”.

Ironically, historians point towards an American army training base base in Kansas as the source; the Australian Nobel Laureate Macfarlane Burnett has said evidence was “strongly suggestive” of the virus starting there and spreading to France via troops.

In much of Europe, the pandemic, while killing millions, was seen as insignificant next to the war. In the US, where there was no combat, there was a lax response.

“In 1918, a city like Sydney was completely shut down,” says Dr Hau. “But in the US the response was not consistent, and it’s not consistent now with COVID. That’s why there’s a similar mess there.

“In Germany I couldn’t find files in the archives about the pandemic, partly because it was diagnosed as something else – a form of pneumonia.

“But if a country is at the brink of collapse and there is a change in the political system, it will be considered a minor thing. The response to a pandemic is conditioned by the historical and political circumstances.”

Read more: Coronavirus: What past pandemics teach us about COVID-19

That’s the societal response. What about an individual response?

Vanessa Clothier is a Monash University lecturer in nursing and midwifery, and was a frontline nurse in emergency departments in Melbourne during the COVID-ravaged winter.

This year was, fittingly, the Year of the Nurse. For her it was a visceral, intense experience over several months that prompted much self-reflection.

The soul-searching came after a shift in mid-March, she says, where “everything changed”. Melbourne had COVID in the community since January and then, in March, the virus-stricken cruise ship Ruby Princess docked in Sydney, disgorging sick passengers that led to 900 infections across Australia.

“I remember walking on to the shift where, like all other EDs, we literally divided our department into two – one area for high-risk COVID patients, and one area for patients that screened as low-risk COVID. In my 24 years of emergency nursing, I had never seen such a massive change to our model of care, and especially a change that occurred in literally 24 hours.

“It was here, it was real, and it was all hands on deck.”

The fear of EDs being overwhelmed

Before this, she says, nurses and health workers had seen the unfolding pandemic scenario in Europe and the US, with TV vision of “overwhelmed” hospitals, refrigeration trucks parked outside hospitals in New York, and a Madrid ice rink turned into a morgue to deal with the dead.

“ED staff are very much accustomed to having ‘busy’ shifts. I often think that what we do in ED is a craft. We turn relative chaos into something that makes sense. We can be ‘busy’, but feel satisfied that we can continue to deliver high-quality care for our patients.

“It can be exhilarating to work in a ‘busy’ ED; however, working in an ‘overwhelmed’ ED was not something I wanted to experience. For me, being ‘overwhelmed’ means that you can no longer deliver the type of patient care you’ve been educated to do.”

The day after the shift when “everything changed”, she had to make serious personal decisions impinging on work, but also family.

“At the time, we had no idea how things would play out. All we had to compare to was what was happening overseas, and at the time it wasn’t good.

“I didn’t want to put myself or my family at risk just because of the job that I do. How would I keep everyone I loved as safe as I could? Would I continue to kiss my kids? There were reports in March of kids having cardiac issues post-COVID – I couldn’t forgive myself if I gave them that. What if I was one of the people that had COVID but displayed no symptoms? What about my parents?

“The research back in March was scant, but was already telling us that the over-65s were most vulnerable. I didn’t want to transmit COVID to my parents.

“I made the decision that day to go and visit them, and hug and kiss for the last time until this was over.”

Concerns for the most vulnerable

Rose Jaspers was forced toward similar questions.

“I was concerned about the spread to the vulnerable population – my parents are aged, and my brother is disabled. I’m heading into the aged population myself. Would I survive if I caught this? I was concerned about the impact it would have on this population, and how we would manage a spread in these specific groups.

“I was concerned about my nursing colleagues at the coalface,” she says. “There was very much a dread that they would be exposed to a deadly virus, and a feeling that they could expose their own loved ones to the same.

“There was so much unknown combined with a generous dollop of social opinion of what could happen.”

Also, no one knew that it might come back in subsequent waves.

“Back then,” Clothier says, “we thought the end of COVID wouldn’t be as elusive.”

But it was. In Melbourne, the second wave had a very long tail; the city had one of the the world’s longest lockdowns. England is now in its second lockdown. France and Germany have imposed strict lockdown laws. Austria, Spain, Belgium, Portugal and Sweden – which initially followed a business-as-usual approach – have done the same.

The longer it goes on, the more hope the community bottles up, and the key to understanding pandemics such as COVID, says Monash historian Dr Susie Protschky, is as a collective experience, not an individual one. It’s something people in hot spots all share, like during war, or after a natural disaster.

Dr Protschky’s specialty is photography and disaster – that is, how a disaster (or pandemic) is represented in personal photographs and video, popular culture and media.

The problem with COVID in this respect is it mainly happened behind closed doors, especially in Australia.

“Everything was shut or locked down,” she says. “The pandemic was difficult to access; it was playing out in ICU wards and in aged care, whereas in some other countries it spilled over into public spaces claimed for treatments. Tent cities in New York, mass graves in other cities. There, you see the public health response to COVID in a way that you don’t here.”

Read more: COVID-19: Physiotherapists on the ICU frontline

She says where images were available, it was distinctly similar to Spanish Flu 100 years ago. The defining image of COVID, she says, is “the empty city”.

“An absence of life, empty streets, images of emptiness. The severe economic downturn has been there, but it’s difficult to represent. The pandemic has intersected with concerns about climate change because photographs and drones were able to show less pollution. The cities emptied and became clear.

“This is an irony of pandemics and some disasters – people struggle with the idea of a world without humans, but the world does fine without us. Nature continues, and sometimes the environment becomes cleaner,” she says.

“We have this existential anxiety about our own ability to survive, but the rest of life exists fine without us.”

She says anti-mask and anti-lockdown protests are also a strong symbol of this – and all – pandemics.

“The street protests that have erupted around the world speak to the issues around every pandemic, which is rights in conflict with each other. We’ve all been asked to put the rights of the community to be safe ahead of individual rights. It’s the idea of rights in conflict with each other in a heavily politicised environment. Every pandemic has bought out the conflict of rights in communities.”

Nurses, meanwhile, and healthcare workers, have been dehumanised because of the full PPE gear they have to wear. All that’s visible is the eyes.

The innate qualities of a nurse – communication, compassion and stamina – were all challenged. Wearing PPE is normal, but not all day, every day, for months.

Read more: COVID-19 and the tolerance of uncertainty: Teaching our frontline healthcare workers how to cope

“It’s incredibly uncomfortable to wear,” says Monash nurse Clothier. “The masks are designed to fit tightly across your face and head, and are designed to prevent virus particles entering your respiratory system.

“As a result, they’re dense and difficult to breathe through, and even discussions with a patient when standing still can leave you quite short of breath. It’s hot to wear full PPE; the face shield can reflect light, making it difficult to see through at times.

“It’s harder to talk to people – it’s hard to hear, and it’s hard to be heard. Much of the communication we do in healthcare is non-verbal; the look of empathy or understanding on your face, touching a patient’s arm to communicate – ‘You are not alone, and I’m here for you’.

“Even just smiling is not easily communicated behind a mask. I spend a lot of my day consciously crinkling my eyes so patients, especially kids, and colleagues know I’m hearing them – this is one of the only forms of non-verbal feedback I’m left with,” Clothier says.

The effect – and the way this was communicated to the public – was with the language of war, says Dr Protschky.

“‘'Frontline’ is a term that comes from conflict zones,” she says. “The idea that healthcare workers are the first line of defence. It’s 20 years since the war in Iraq, and since then the public have got used to the idea of people in combat being covered in protective gear, like specialists dismantling explosive devices.

“In some ways it translates to us because we know combatants look like that. But if we flip that, we also know that healthcare workers are some of the most vulnerable people in a pandemic. They’re not just fighters.

“The PPE often hasn’t been sufficient. That protective gear is a fragile shell.”