An innovative Monash University study into intimate partner violence (IPV) and young women – some as young as 17– has also produced a zine showing key findings and also personal artwork by the participants.

The study is part of a PhD by Bianca Johnston from the Department of Social Work in the School of Primary and Allied Health Care. It shows that the ways young women experience IPV can be overlooked.

She says that by using a combination of their voices and visual artworks (“visual ethnography”), it can help other young women to know that experiencing abuse isn’t acceptable and that safety, survival, resistance, recovery and healing are possible.

Johnston worked as a social worker for 18 years.

“A lot of my experiences of working with young people has been about thinking about the ways that information can be conveyed to them that’s accessible and on their own terms,” she tells Lens.

“But it also impacted the way I approached the research, because I wanted to provide the opportunity for the young woman to express themselves however they liked. That's where the creative art component came from.

“I never actually knew what to expect. The plan was whatever they made, we’d style and photograph together, and then the zine was developed as a way to give the research back to the young woman, and to young women and practitioners more broadly.”

Johnston is supervised by Monash University’s Associate Professor Catherine Flynn and Australian National University’s Associate Professor Faith Gordon. The study looks at the lives of 12 young women, aged 16-24, all of whom had experienced IPV, often in more than one relationship.

Most of the young women first experienced IPV when they were 15-18 years old. The 12 young women were from both metropolitan areas as well as rural and regional areas across Victoria, and from diverse cultural backgrounds including Caucasian, Northern African, Caribbean, Central European, Macedonian, Greek, Vietnamese and Italian. Four young women identified as Aboriginal Australians and one identified as Torres Strait Islander.

Striking and diverse art

The artworks are striking, and equally diverse. “Shannon” (pseudonyms were used) drew a tearful eye with watercolours to represent hope, she says, because there’s still light in the eye.

“Michelle” drew a Japanese Enso circle with tattoo ink to show “the start of the relationship where you feel like yourself, and then you kinda fade away and then build yourself back up again”.

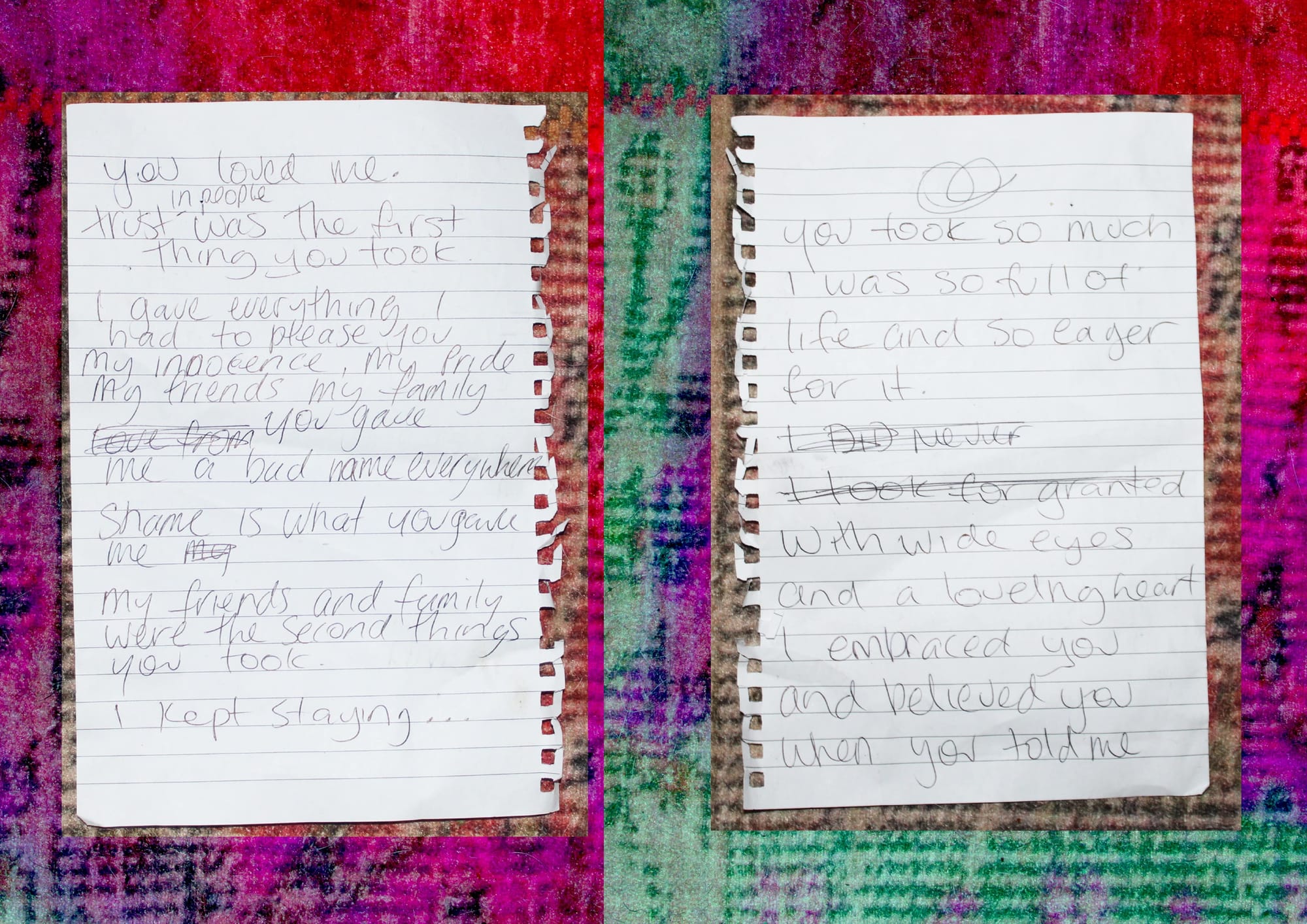

“Squid”, meanwhile, wrote a letter to the ex-partner who abused her. The artwork is her handwriting on notebook pages – “so many memories mark my body …how do I trust myself again?”.

Squid, Johnston says, found closure through the process.

“She is so incredibly brave. All of the young women are so brave and all of them contributed to the research because they really wanted to make it better for other young women, which I think is just a real testament to their heart and wanting to use their experiences to help others.

“Squid’s piece was so powerful because for her it was a way of having closure and being able to say things that she felt she hadn’t been able to say. She had a few different goes writing that letter, and it changed over time as her healing journey changed.”

Young women felt misundersood

The study revealed young women can be unsure where to seek help, and many of those who participated didn’t know if there were any services to assist, meaning they often relied on themselves to resist the abuse and stay safe.

Some said they felt misunderstood or misidentified. Johnston says youth IPV is often merged into other forms of family violence despite it being very different, and the young women she spoke to felt their experiences of IPV were not taken seriously and dismissed as “soap drama” because of their age.

One young woman involved in the study, “Abey”, described IPV as “like being controlled, being told what to do, being told what not to do, like being forced to do stuff … being physical. It’s not even just physical; it's mental, emotional, like it’s a lot of stuff involved.”

The study identifies the “journey” of IPV for young women through various stages – relationship onset; escalation; survival; terminating relationships; and recovery and healing.

It shows the spectrum of abuse through these stages, which Johnston explains can come with a “frequency and severity” leading to “incredibly serious impacts on their lives”, including hypervigilance.

Yet it was often suffered in a vacuum – “unlike adult women, they don’t have any services they could access or numbers to call, and they were just trying to work it out themselves” at what she describes as “a significant point in their development and their identity formation”.

“These are some of the first relationships in these young women’s lives,” she says. “When you talk about psychological abuse, a lot of what young women experience really impacts their self-esteem, and their confidence and their trust in others, like we've seen in Squid's letter.”

Giving young women visability

The zine – titled F*ck this, I want to get my life back (published separately but forming part of Johnston’s PhD) – shows that some of the young women wrote affirmations to themselves, which she says is “their way of trying to remind themselves that they're good people and that they’re loved and loveable, trying to figure out who they were again after the relationship”.

She says the aim is to understand and provide visibility to what young women are already doing to keep themselves safe, recover and heal in the face of IPV, and ultimately inform youth-informed strategies in direct social work practice.

“I feel that it’s a really emerging area of research in Australia. One thing that I think makes this study unique is the fact that there’s previously been a big focus on risk prevention, which is really important, because the risks that they experience are real, and obviously we want to prevent this.

“But what is an equally important part is resistance and survival and recovery and healing, and I don’t see as much attention on that.”

This article was co-authored with Associate Professor Faith Gordon, Deputy Associate Dean of Research at the ANU College of Law, and former Monash academic.