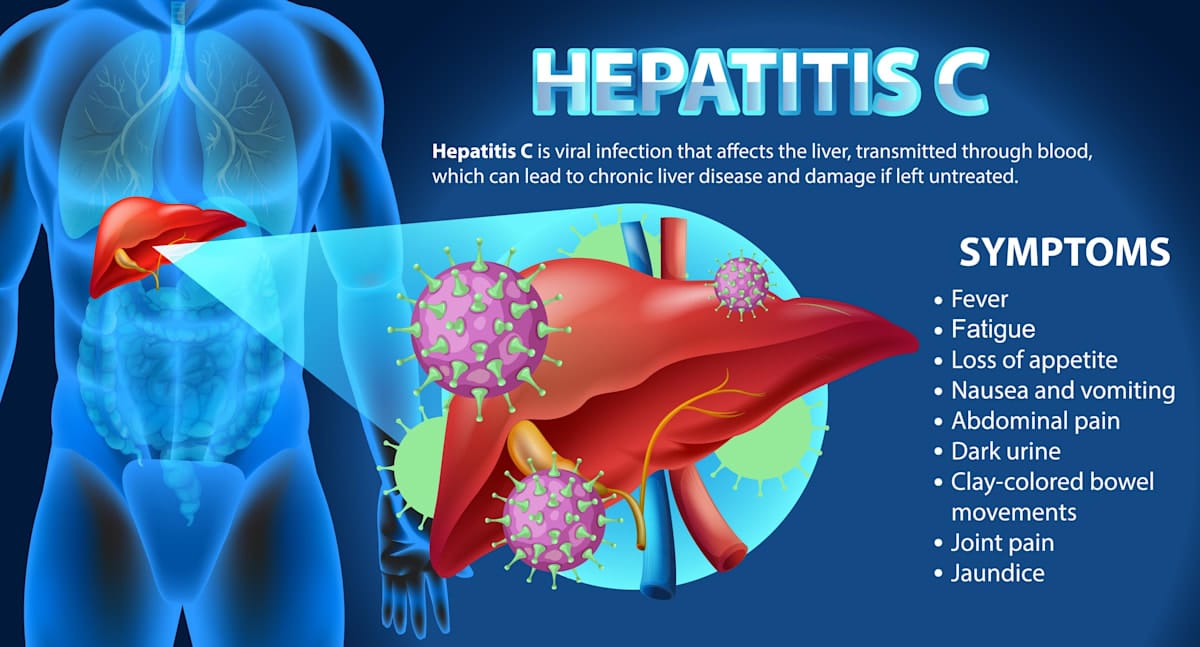

Hepatitis C (HCV) is an inflammatory liver disease that can lead to severe and debilitating complications such as liver scarring, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. HCV is also linked to other complications such as chronic fatigue, diabetes, and neurological disorders.

Globally, HCV poses a significant public health challenge.

In 2015, it was estimated that 71 million people globally were chronically infected, with 1.75 million new infections occurring annually.

Did you know you can live with hepatitis C for years without knowing it?

— PAHO/WHO (@pahowho) July 28, 2025

💊 The good news is it can be cured, often in just 3 months.

Get tested. Get treated.

⤵️ Learn more pic.twitter.com/01UjiuYqfK

HCV claims a staggeringly high number of lives, with approximately 500,000 deaths each year caused by HCV-related liver diseases or complications.

The global burden of HCV, however, is not evenly distributed; the vast majority of those affected (75% to 85%) reside in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). As such, the World Health Organisation (WHO) set an ambitious goal to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health concern by 2030, aiming for a 90% reduction in new infections and an 80% treatment rate among diagnosed individuals.

Treatment of HCV has, until recently, proven to be difficult. For decades, the standard of care for HCV relied on interferon-based regimens, often combined with ribavirin. These treatments, administered via injections, were notoriously difficult for patients to tolerate, and frequently caused severe side-effects such as fever, flu-like symptoms, depression, and anaemia.

To make matters worse, cure rates were modest (between 50% to 80%), and treatment courses were long, often lasting between six months to a year. Unsurprisingly, many patients struggled to complete the full course.

The HCV treatment landscape changed dramatically with the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), which began receiving regulatory approval around 2011.

Unlike older therapies, DAAs directly interfere with the virus’s replication cycle, leading to significantly improved outcomes.

The latest generation of DAAs are highly efficacious, safe, and well-tolerated medicines that are taken orally for a much shorter duration, typically between eight to 12 weeks.

DAAs have high cure rates that often exceed 90%. The introduction of DAAs has not only improved cure rates, but also profoundly impacted patient health by reducing the long-term complications of HCV.

Early treatment, before the onset of liver cirrhosis, can prevent the most severe complications of the disease, such as liver cancer. Even in cases where cirrhosis has taken place, DAA treatment can halt disease progression, reducing the risk of liver cancer and the need for liver transplantation.

Patients with HCV have often struggled to gain access to DAA treatment – in large part due to their high prices. For many years, pharmaceutical companies set such high prices for DAAs that even in wealthy nations, DAA treatment had to be rationed.

For example, treatment with sofosbuvir was priced by the pharmaceutical company Gilead at US$84,000 for a 12-week course in the United States, despite studies estimating the manufacturing cost of sofosbuvir between US$68 to $136.

Each year nearly 400,000 people die from complications of hepatitis C virus (HCV). Its cured with 12 weeks of once-daily oral medicines. High prices have prevented access to life-saving HCV treatment.https://t.co/rNEFO3Yikx#WorldHepatitisDay #MakeMedicinesAffordable

— ITPC Global (@ITPCglobal) July 28, 2025

Even significantly discounted prices, such as France’s negotiated US$47,000 for sofosbuvir, were financially crippling, with the cost of treating all infected citizens reaching tens of billions of dollars. These high prices caused significant public outrage in high-income countries.

The impact of these prices was particularly devastating in LMICs, rendering DAA treatments effectively inaccessible.

While some companies agreed to voluntary licensing agreements that provided the poorest countries access to lower-priced generic versions of DAAs, these agreements often excluded many middle-income countries, leaving approximately 42 million HCV patients without treatment.

This created a “middle-income trap” where countries were neither poor enough for access to generics nor rich enough to afford originator prices.

For example, while Indonesia received a reduced price of US$900 per course for sofosbuvir, the cost remained prohibitive. Treating its nine million patients would cost US$8 billion, equivalent to its entire public healthcare expenditure in 2011.

Patients with HCV in LMICs struggle with more than just DAA pricing. Other barriers exist, including the lack of national HCV programs in many countries, poor public awareness and stigma, and limited screening and diagnostic services.

Treatment access advocacy

In response to the challenges, a global HCV treatment access movement has emerged, spearheaded by patient advocacy groups, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and forward-thinking governments.

These efforts have focused on fostering public health approaches that prioritise patient access and treatment affordability over profits, using multi-sectoral collaborations, drug development, and regulatory initiatives.

A prime example of this is Malaysia’s public health campaign to eliminate HCV.

Initially facing unaffordable DAA prices and exclusion from voluntary licensing agreements, the Malaysian government took decisive action by issuing a government-use license to source generic sofosbuvir, enabling it to procure the DAA at about US$300 per treatment course, a massive reduction from the original price of $12,000.

The Malaysian government also worked with several NGOs such as the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) and other Global South organisations on collaborative research and development projects to develop affordable HCV treatments.

One new DAA, ravidasvir, emerged from this effort. Ravidasvir, an NS5A inhibitor, was identified by DNDi as a promising candidate, with early phase three trials conducted in Egypt by Pharco Pharmaceuticals demonstrating excellent efficacy – 100% cure rates in non-cirrhotic patients, and 94% in cirrhotic genotype four patients when combined with sofosbuvir.

The Ministry of Health Malaysia worked with DNDi and the Ministry of Public Health in Thailand to conduct the STORM-C-1 clinical trials in Malaysia and Thailand, which demonstrated that ravidasvir combined with sofosbuvir had a high cure rate of 97%, had no clinically significant drug interactions with antiretrovirals, and was well-tolerated with a favourable safety profile.

Equally important was the commitment from Pharco and Malaysian pharmaceutical company Pharmaniaga to agree to make ravidasvir commercially available for public health use at US$294 or less. This was dramatically lower than originator prices. and expected to decrease further with increased sales volumes and competition.

With the availability of affordable DAA treatment, Malaysia has taken a comprehensive approach, including providing free HCV treatment in public healthcare facilities and integrating screening into primary healthcare that has led to a 20-fold increase in annual treatment coverage.

Crucially, despite the significant scale-up in diagnosis and treatment, public healthcare expenditure has remained stable. This highlights the potential for LMIC-based collaborative public health approaches to address public health concerns such as HCV, foster local research and development capacity, and self-reliance in LMICs.

The global elimination of HCV is a realistic possibility, driven by the remarkable advancements in DAA therapies. Achieving WHO’s 2030 elimination targets, however, requires a multifaceted approach, including strong political and governmental leadership to prioritise HCV elimination and overcome restrictive intellectual property barriers, innovative service delivery models (especially for vulnerable populations), and the building of strategic partnerships between governments, industry, civil society and patient groups to ensure equitable access.

By working together and prioritising public health, the vision of a world free from HCV can indeed become a reality.