It all started during the COVID-19 pandemic and the global and domestic travel restrictions. For Monash University’s Professor Ram Nataraja, the travel bans meant he and his team could no longer train surgeons from interstate and overseas as they had been.

The training – on briefcase-sized surgery simulators – ground to a halt.

What to do? Pivot.

“We decided to send out the simulators to the surgical trainees who had signed up,” he says. “We posted them out and then they had the simulators in their own houses. We designed a six-week course based around that and started to run it – a Monash online surgical training course.”

What is PIVOTS?

The idea took off and evolved. Now it’s a fully-fledged Australia-Pacific project, called PIVOTS (Pacific Islands Virtual Online Training in Surgery), which has just launched its newest phase in the Solomon Islands.

Elsewhere, it’s trained more than 200 surgeons, the majority women, in Fiji, Vanuatu and Samoa using this simulation-based and culturally-tailored approach.

Professor Nataraja developed the program with the Monash Children’s Hospital Simulation Centre (MCS), Fiji National University (FNU) and the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS). It’s delivered free through the RACS Global Health Pacific Islands Program (PIP).

Professor Nataraja is from the Department of Paediatrics in the School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health.

“The Pacific Island uptake has been huge,” he says. “We've had 260 people through, with Fiji National University, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Samoa, and Vanuatu.

“But their mindset changed during COVID as well. We had suggested doing simulation-based training with them previously, and the answer was they didn’t really feel it could work, so there was a paradigm shift in the Pacific Islands, during COVID, where they actually became much more receptive to it because they just didn't have visiting teams for three years, which was the traditional model.

“So all education stopped, all support stopped, apart from the odd Zoom session.

“We had a ready, prepared package, which we culturally adapted,” he says. “We started a pilot in Fiji, which took off. Then we spread to different islands from there. It's building and building.”

Simulators and virtual tools

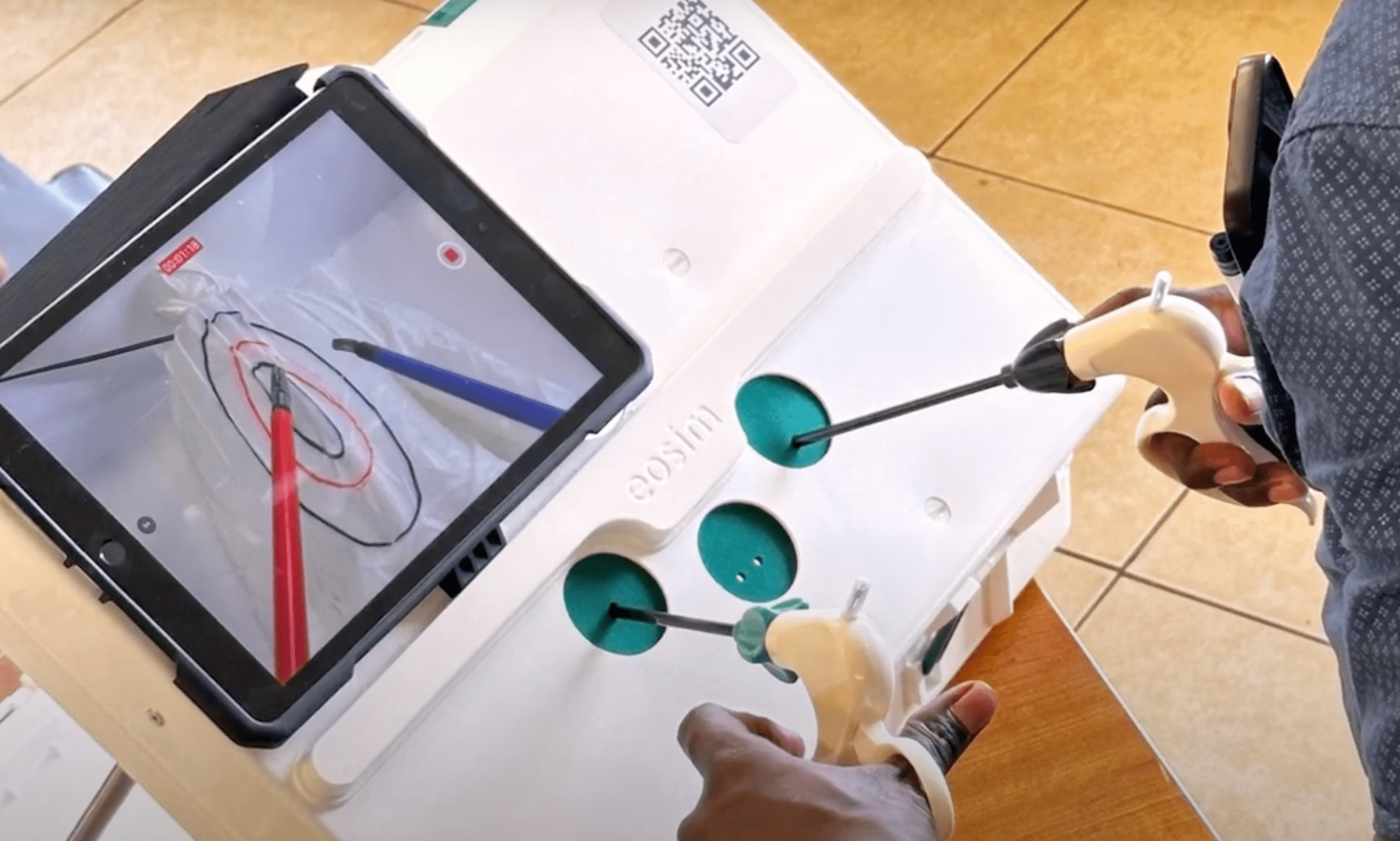

It’s called simulation-based education (SBE), combined with virtual educational methodology and the technology. A typical PIVOTS session has separate aspects of training, the first of which is using the briefcase-size training simulators.

The trainees are all qualified doctors extending their training.

Another aspect is the online Moodle resources on core laparoscopic and surgical techniques. The third is what Professor Nataraja calls the “cognitive” aspects – “for the more cognitive aspects of surgical practice, like breaking bad news, dealing with complications, situational awareness, writing operation notes, and all those other skills, which are big, important factors to patient outcomes”.

He explains that the simulators use tablets as well as a “box” for the laparoscopic instruments to go inside. “Then we couple that with technology that monitors the instrument movements. So they also get system-generated feedback about the speed of the instruments, how much time they're off screen, the acceleration and coordination, and all those aspects of handedness that go along with it.

“We can also upload assessments, and we do webinars also where we can see the inside of a trainee’s simulator and we can watch them doing tasks.

“We must have about 60 simulators throughout the Pacific right now, where people are using them constantly, getting feedback from the simulator themselves, and also from us when we run the programs.”

Professor Nataraja says for the Pacific nations it’s an ideal time to train in laparoscopic surgery.

“When I started training, when we first introduced laparoscopy, there was an increase in complications and patients were harmed by it because we didn't train them. So, actually, it's an ideal time to train them, because we're catching the beginning of their learning curve.”

“The benefit of this is clear – better surgeons and better patient outcomes.”

The non-technical or cognitive skills are proving invaluable.

“The funny thing is,” he says, “when I designed the course it was very much centred around those skills, because they're so important, and people didn't sign up for it. Then I introduced laparoscopy and related things for surgical training, and then people started signing up.

“But then the interesting thing is at the end of the course, when we get feedback, the things that they always say are the most impactful for them for their future practice was the cognitive skills – ‘they taught me how to write an operation note, they taught me how to drape’.”

Surgeons are by nature technical, he says, which is how it should be.

“But in my world of paediatric surgery, we've long realised that that's not the whole story. The technical stuff is important, but actually all the cognitive and non-technical skills make a patient's journey better, but also improve outcomes and actually just make everything run more efficiently and smoothly.”

Training surgeons in low-resource settings

The PIVOTS team had to tweak the existing Australian courses for use in the Pacific as a “low-resource setting” that became about continual improvement rather than absolute gold-standards, and also about breaking down the hierarchies in Pacific surgery by showing a more inclusive way of doing things.

In Fiji there’s now a home-based program, where the surgeons of the future can take the simulators and the equipment home, partly because at the University in Suva there’s limited space. In Papua New Guinea, the program has supplied wireless dongles because of limited internet access.

With the newest project in the Solomon Islands, PIVOTS has expanded still further.

“It's a privilege to work with them,” says Professor Nataraja, “and they're doing really, really well. I think it'd be good to build on the program, because they want more, and they want different aspects and different things like research and clinical governance as well. So they're really keen to improve and upscale.

“The benefit of this is clear – better surgeons and better patient outcomes.”