“I first heard the words ‘ectopic pregnancy’ when it happened to me – life changed in an instant.”

This first-person account – by a co-author with lived experience – is part of a new global review led by Monash University, and published in Nature Reviews Disease Primers. It explores one of the most misunderstood complications in early pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, which affects about 1% of pregnancies worldwide and is the leading cause of death in the first trimester.

The review is powerful due to the lived-experience perspective shared by a co-author. She provides a firsthand account of the psychological journey after an ectopic pregnancy. Her story is not positioned in the primer (or explainer) as a clinical vignette, but, the researchers say, a recognised contribution to scientific understanding.

“I was devastated,” she writes. “My doctors saved my life. The immediate weeks were preoccupied with physical recovery from surgery… Emotionally, there was a mix of feelings. I grieved the loss of a fallopian tube and our pregnancy. I felt guilt that my body had let me down.

“Perhaps knowing that it is possible to go on to have a baby and life can resettle may humbly offer hope to anyone needing it after an ectopic pregnancy. Being part of this project gave my experience purpose – and I hope it helps others feel less alone.”

The review, invited by the editors of Nature Reviews Disease Primers, was led by Dr Krystle Chong and Professor Ben Mol, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology within the School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health and Monash University. It’s the most comprehensive summary to date on ectopic pregnancy (EP) research, covering diagnosis, management, global inequities, and the psychological toll of pregnancy loss.

Nature Reviews Disease Primers is published by leading medical journal Nature, and the primers zero in on a specific disease, summarise the global research and evidence, and lay the groundwork for more, from brain conditions to blood cells, skin disorders and more, published once a week.

“We wanted to centre both clinical knowledge and human experience,” says Dr Chong. “It was important to us that the patient voice was not just included, but heard in full.”

What is ectopic pregnancy?

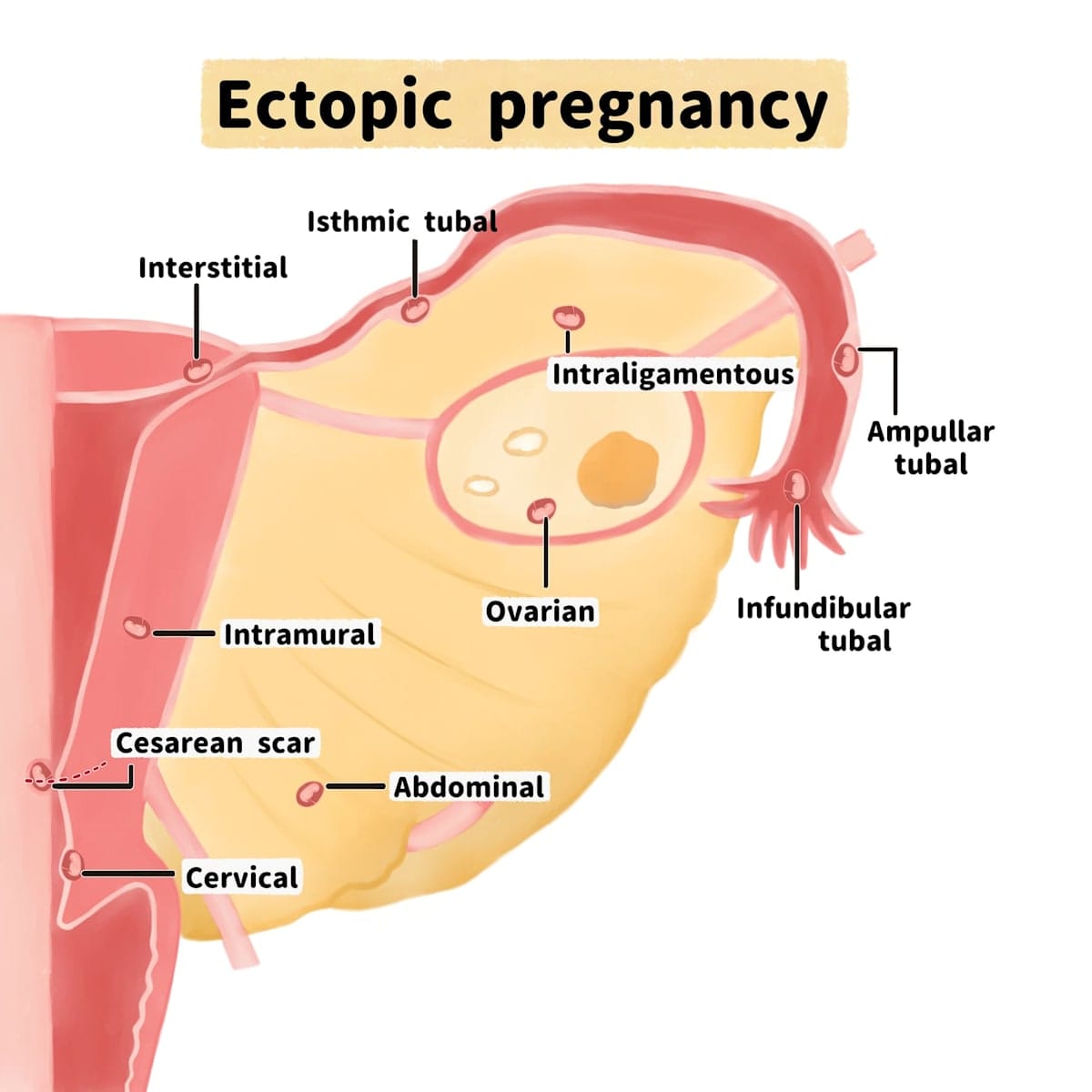

It occurs when a fertilised egg implants outside the uterus. Most often, this happens in a fallopian tube, but it can also occur in other locations, including a previous caesarean scar, the cervix, or even the abdominal cavity. These pregnancies are not viable and can pose serious, life-threatening risks.

“This is a condition where fast diagnosis and clear management can be life-saving,” says Dr Chong, a clinician-researcher in obstetrics and gynecology. “But we also need to think beyond the immediate emergency and consider the person – what they’ve lost, what they’re facing, and how we support them through that.”

The primer outlines that complications can be serious, including rupture of the fallopian tube, haemorrhage and blood loss, and “ultimately increase[s] the risk of maternal death”.

Patients can suffer chronic pain afterwards, as well as infertility and psychological distress. It says clinicians should be patient-centred with “acknowledgement of potential psychological distress associated with pregnancy loss and reduced future fertility”, because future fertility – the ability to become pregnant again – “is an important but often overlooked aspect in the management of ectopic pregnancy”.

Diagnosis: The race against time

The paper stresses that early diagnosis is critical in ectopic pregnancy. The symptoms – abdominal pain, bleeding, dizziness – can overlap with other pregnancy complications or even routine discomfort. In a health system under pressure, or in settings without specialist resources, diagnosis can be delayed, it says.

Early pregnancy relies on precise hormonal signalling to support implantation and development. A key hormone, hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), produced by placental tissue, stimulates progesterone production to maintain the uterine lining.

This hormonal support continues for about six to eight weeks, until the placenta takes over. In ectopic pregnancy – where the fertilised egg implants outside the uterus—this signalling is disrupted, affecting both development and detection.

All clinicians, it says, need to “think ectopic” when assessing women of reproductive age with abdominal pain and bleeding, including performing urine pregnancy tests, in any healthcare setting, and even clinically stable women should have an ultrasound within 24 hours.

The review outlines how modern diagnostic tools, including sensitive blood tests for hCG and high-resolution ultrasound, have significantly improved outcomes in high-income countries.

But access remains unequal. In many parts of the world, particularly where sexually-transmitted infections such as chlamydia are more prevalent, women face both higher risk and fewer resources. Chlamydia is an STI that can damage the fallopian tubes. Rates of EP are high in regions of Africa and Latin America.

“There is a huge global equity issue,” says Professor Mol, who leads the Evidence-Based Women’s Health Care Research Group at Monash University. “The same condition that is usually survivable in one setting can be fatal in another.”

The review shows that women in higher-income countries clearly do better. “There was a significant difference in both the incidence and associated maternal mortality of EP in lower- and middle-income countries versus higher-income countries.”

Treatment options – and difficult choices

There are three main approaches to managing ectopic pregnancy, depending on how early it’s detected and the patient’s condition:

- Expectant management, or watchful waiting, for stable patients with declining hormone levels and no sign of rupture.

- Medical treatment using methotrexate, a drug that stops cell growth and allows the pregnancy to resolve without surgery.

- Surgical intervention, including either removal of the fallopian tube (salpingectomy) or removal of the pregnancy while preserving the tube (salpingostomy).

The review explains that each approach has implications for future fertility, especially surgery. For many patients, there’s no time for detailed discussion. The review highlights the need for informed consent that includes clear, compassionate information about future reproductive health and emotional wellbeing.

“There is no ‘safe size’ of ectopic mass,” the authors note. “All patients should be counselled regarding risk of rupture and supported with a safety plan for seeking help.”

Psychological impact still overlooked

The review examines how the emotional aftermath of ectopic pregnancy is often hidden – grief, guilt, and fear of recurrence can linger long after physical recovery, and many people describe feeling isolated in their experience, particularly when future fertility feels uncertain.

It highlights the importance of recognising this emotional burden. It recommends follow-up care that includes not only clinical monitoring, but also access to psychological support and fertility counselling. About one in 10 people who experience an ectopic pregnancy will face another – so care should be proactive and personal.

The co-author’s account included in the review offers rare insight into this journey. She describes the shock of diagnosis, the emotional weight of loss, and the long path to healing, supported by loved ones and healthcare professionals. Sharing her experience, she says, was a way to offer hope to others.

“Being part of this project gave my experience purpose – and I hope it helps others feel less alone.”

Shaping care for the future

The Monash team say that by compiling this review, they aim to equip clinicians, policymakers and researchers with a shared foundation for more responsive, patient-centred care. The review calls for improved early-pregnancy care pathways, greater clinician awareness of ectopic pregnancy, and the integration of lived experience into both practice and research.

It includes international perspectives and examples of system-level interventions, such as expanded weekend early-pregnancy assessment services in the UK, which have helped reduce emergency admissions.

“This isn’t just about diagnosis and treatment,” says Professor Mol. “It’s about acknowledging that healthcare should see the whole person – their medical needs, yes, but also their emotional journey and future hopes.”