It was the spring of 1988 in Carlton, Melbourne. Erica Tandori was a young painter at the Victorian College of the Arts, having already worked as a journalist and theatre critic. She was – and is – a deeply visual person.

But something wasn’t right. She looked at a white breadcrumb on a blue kitchen bench that day, and it kept disappearing. Then, later, the red numbers in her digital clock weren’t staying still. “They were fracturing,” she says, “and dissolving into the blackness.”

She thought she might have a brain tumour. She saw two specialists, the second of whom told her she was going blind. He also told her she had no choice but to leave art behind.

As outlined in a new paper by Dr Tandori and Monash University researcher Professor Jamie Rossjohn in the journal Cell, this news was hard to take.

“I was incredulous,” she writes – and had many questions. How blind? How long will it take? Will I be able to see anything? “But I'm going to the best art school in the country … I wonder if there’s anything more terrifying than for an artist to lose their vision?”

Dr Tandori was diagnosed with Stargardt disease – juvenile macular degeneration – a genetic eye condition leading to a slow loss of vision in both eyes, and characterised by blurred or distorted vision, and blank patches.

But rather than leaving art school, she stayed, and kept painting, and also branched out into acting.

However, by 1989 her failing vision was now all but gone, and Dr Tandori was deemed legally blind. She was 23. She left art school, and left Melbourne for Sydney, where she worked as an actor in film and TV, and a singer with a recording contract.

“Vision is a continuum,” she says. “You may start off with what you think is perfect vision, and then it may deteriorate, and there’s such a range between good vision and no light perception at all.

“That space in there is what I call the void, between vision and non-vision, and it’s a weird space between two worlds.

“So many things were affected,” she says. “The ability to drive, to see faces, the ability to read. Your world shrinks.” She found she could still paint, but only up very close to the canvas.

She moved back to Melbourne, had two kids, then went back to VCA, while painting and selling her work, and came away with a PHD in philosophy.

Her vision now is such that she can’t see much unless up very close. “Faces dissolve into the background. But there's also a lot of light, like electrical light, sort of going everywhere. And if I blink, there are those electrical circles of green. It's actually really exhausting.”

Recently, in London, Dr Tandori went to see some JMW Turner paintings, and was struck by them.

“There's so much of my vision in those Turner paintings. Explosions of colour and turbulence in the visual field that connects so directly to an emotional state, and almost a philosophical parallel with the state of the world.”

Employing disabled people in lab roles

In 2017, Professor Rossjohn made the call, as he writes in the Cell paper, to “proactively employ people with disabilities” in his biomedicine lab, and found that job-seekers would often agree to work as interns without pay, but decided instead to offer three-month paid positions in administrative or technical roles in the lab.

"Disability-focused employment agencies provided additional workplace adjustments as needed for our new team members, including assistive technologies, sign language interpreters, and disability awareness training for all our lab staff.”

The Rossjohn Lab also hosted an extended internship for a young scientist with a disability – with a master’s of medical laboratory science degree. Afterwards, he was able to find a permanent job in biomedicine, with his support worker passing on that his time in the lab had been life-changing.

Another researcher is now doing further biomedical and health science studies at Monash, while another biomedicine intern pivoted to computational biology, and is now completing a PhD in genetics, also at Monash.

Read more: ‘It’s discovery science. You may have a setback, but you don’t take it lying down’

The lab has employed more than 15 staff who identify as having a disability, and admits to initial issues – “major hurdles” – when dealing with human resources, particularly regarding issues of defining and assessing job descriptions and workplace safety.

“Witnessing the positive experiences of our interns has been heartwarming and immensely rewarding,” Professor Rossjohn says. “There’s a recognition that the key to success lies in opportunities afforded to us in life.

“The inclusion of interns with disabilities has contributed greatly to the cultural life of our lab, broadening understanding and revealing new perspectives and ideas through diversity.”

The beginnings of Sensory Science

Then, in 2018, Dr Tandori was hired as an intern after being recommended by Vision Australia.

Professor Rossjohn explains this came from the “germ of an idea” to make a science exhibition for the blind and those with low vision. “For centuries, scientists have been studying the microscopic world of cells and microbes, yet the microscope, and powerful versions thereof, are inaccessible to this community. There was a desire, and a need, to bring the beauty of the microscope to life for the low-vision and blind community.”

The concept was called Sensory Science, and the first exhibition was held at the University, along with more internships.

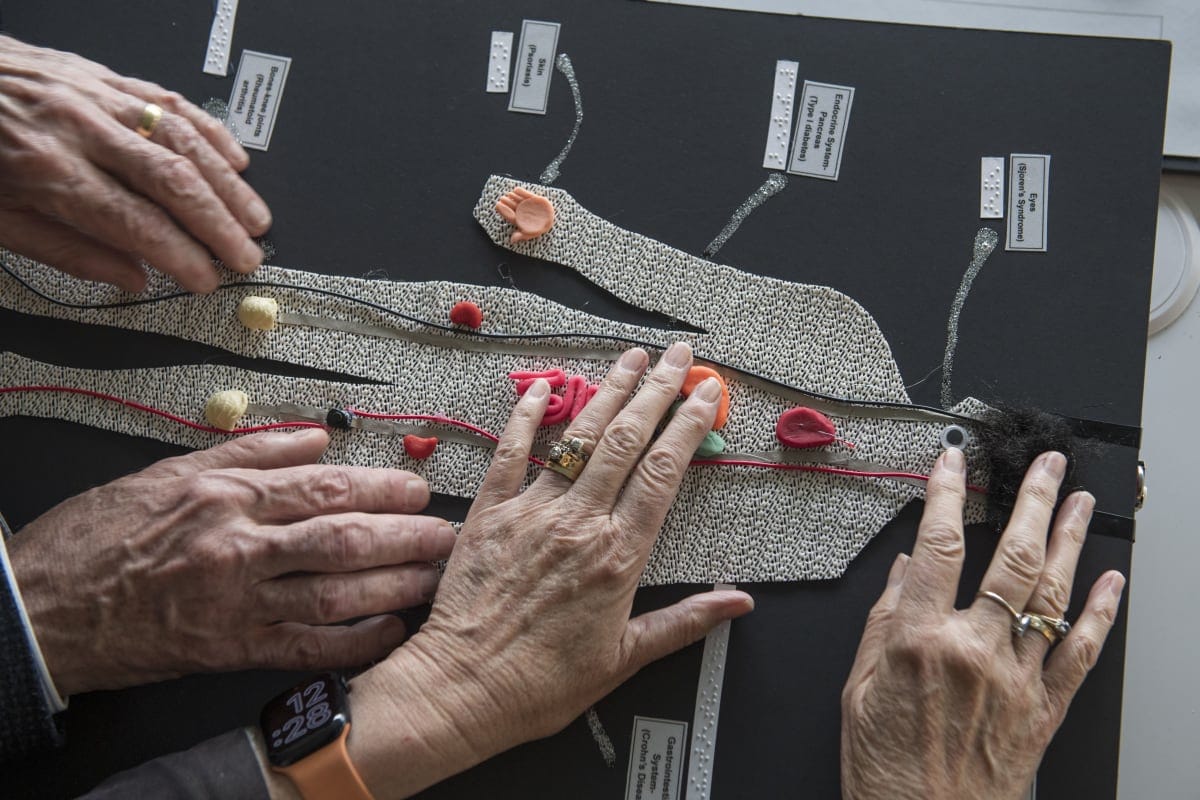

Dr Tandori’s art for the lab consists of tactile representations and huge 3D models of immune cells, viruses, bacteria, proteins, and Braille-inspired amino acid sculptures, which she made after working with lab scientists to better-understand them.

She used common objects as well as oil paint, plus paper clay, food and seeds. The concept is art’s potential to help communicate and research science and medicine as a “multisensory language”.

More Sensory Science exhibitions have followed, including at Cambridge University in the UK for the Cambridge Festival in March, and at an international electronic arts symposium in Brisbane, this time exhibiting Sensory Science interactive science books designed with Dr Stuart Favilla and Dr James Marshall, from Swinburne University of Technology.

Sensory Science has won the Monash University 2018 Vice-Chancellor’s Diversity and Inclusion Award, been a 2019 finalist in the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science Eureka Prize for STEM Inclusion, and in 2020 was a finalist in the “Science Breakthroughs of the Year – Science in the Arts” category at the Falling Walls Conference and Berlin Science Week.

Making science more accessible

Dr Tandori says she wants to “awaken” understandings regarding science for those with limited access to it.

“Feel the shape, the form, the textures. It brings us back to emotion and memory, a deeper understanding. So that's what I'm trying to awaken in multisensory approaches to articulating these viruses and cells and their interactions.

“We need our voices heard. I just think that that multisensory approach to engaging with the world, not just in science communication, not just in the education space, but in a full engagement and a reawakening of what is going on in life could be a wonderful approach.”

She says – unequivocally – that science hasn’t always existed, but art has.

“At one stage,” she says, “they were one and the same. If you were to tell da Vinci, ‘That's not science, that's just art’, he would've poked you in the eye with his brush.”