Dr Erica Tandori may be legally blind, but as an artist she's honed her skills to help people experience and touch the invisible world of molecular biology.

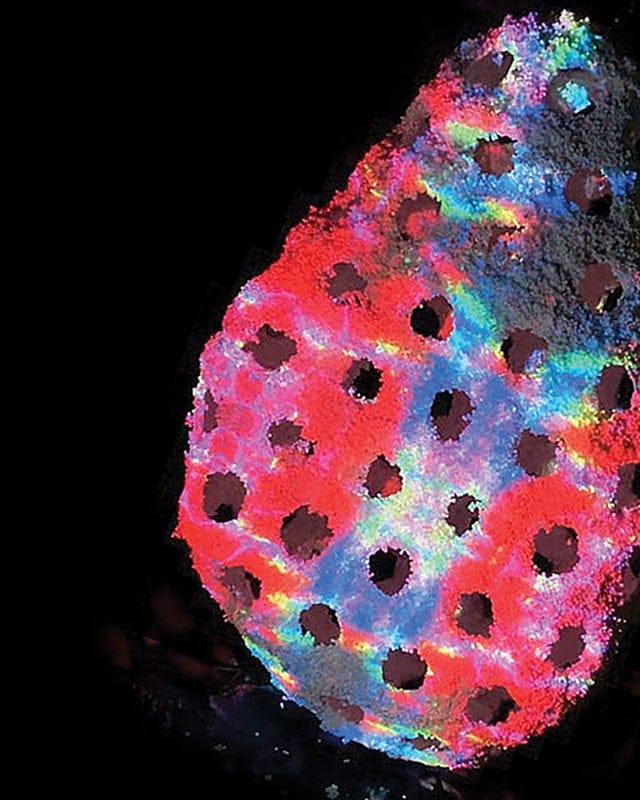

Her most recent work deals with the minutiae that form the focus of biomedical research in the realm of viruses and antibodies.

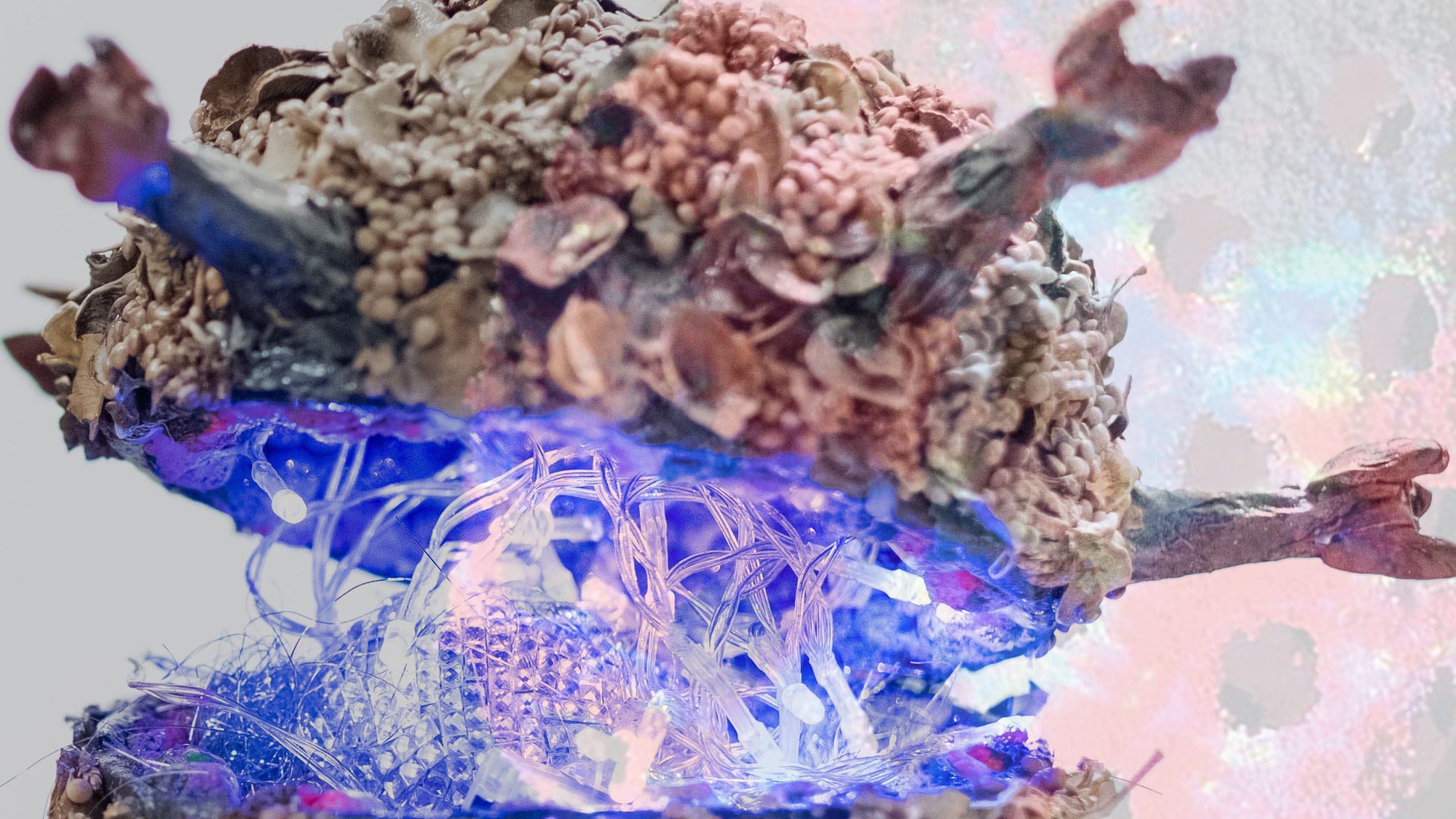

In her hands, science’s near-incomprehensible, two-dimensional images are transformed into marvellously detailed, three-dimensional sculptures or Braille-like glyphs that can be held, felt and explored.

The goal is to create access to the world of molecular biology for blind and vision-impaired people, says Tandori, who is artist-in-residence at the Rossjohn Laboratory within Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI). This position was created by Professor Jamie Rossjohn, former head of the BDI’s Infection and Immunity Program, to empower people with a disability to pursue careers in science.

“Viruses blow my mind. The way they break apart yet retain the ability to reassemble themselves – it’s cunning, it’s intelligent.”

Drawing on her awe and wonder of the subject matter, Tandori has created pieces that thrill the vision impaired youngsters she most wants to inspire. Reactions to her work shown at Rossjohn Lab’s 2018-19 Sensory Scientific Exhibition and Discovery Days are testament to that.

Yet there’s something about how Tandori bridges the art-science divide that allows her to concurrently engage the public and inspire scientists.

“There is this amazing potential to open up dialogues by bringing other senses into the experience of understanding science,” she says. “That means we can explore whether art has a role achieving a deeper understanding of molecular structures. I find that a delicious challenge.”

Anchoring the production of these pieces was her visceral reaction to a central concept in molecular biology – the idea that the three-dimensional form attained by clusters of atoms dictates that molecule’s higher-order biological functions.

Art gone viral

As an alumna of Monash Art, Design and Architecture (MADA), Tandori sees in this ‘form-function’ relationship a sculptural principle familiar to her from art. It’s proven an expansive source of inspiration and wonder that leaks into her work, and is especially apparent in her latest pieces.

Large enough for a teenager to stand inside, Erica Tandori’s HIV Capsid sculpture was created with cardboard hexagonal shapes covered with millions of tiny foam balls. With music by Stu Favilla, computerised viral mutating lifeforms projected onto the sculpture appear to ‘dance’ in time to the beat, creating a new sensory realm of visual and aural perceptions.

As the recipient of a Victorian Government Creators Fund grant, she’s using sculptural techniques to explore a subject that has brought the world to a standstill – viruses. The work is due to be exhibited at the UN AI for Good Global Summit. “Viruses blow my mind,” she says. “The way they break apart yet retain the ability to reassemble themselves – it’s cunning, it’s intelligent.”

With these pieces, the entities best-known for their smallness are transformed into enormous 3D sculptures that allow people to clamber inside and become, as she says, the virion’s RNA.

In classic Tandori style, there’s an Alice in Wonderland kind of intrigue to the size reversal in which it’s humans that infect and invade the body of the virus. Included is a sculpture of COVID-19.

“To be able to hold a mitochondrion and feel its inner working, or to step into a virus – it amounts to an immersion into tactile forms that are imbued with scientific meaning. That does something to blind people,” she says.

Life model

Underlying these achievements is Tandori’s experience of sight loss that began at age 22. The diagnosis – an incurable form of juvenile macular dystrophy called Stargardt’s disease – has, over several years, shattered all but the cells in her retina responsible for black and white peripheral vision.

There was terror at the diagnosis back in 1988, and exasperation at how little medicine knew or cared about the patient’s inner experience of going blind. It’s a subject she explored in her PhD thesis on art and ophthalmology.

But in hindsight, it was her encroaching blindness that pushed Tandori to embrace the artistic talent she had disdained as a fully sighted woman pursuing undergraduate studies in journalism, English literature and philosophy.

She got over the terror of being an artist who had lost her sight, and she leant on the ability of her brain to compensate and her mind to adapt.

“I’m blind, big whoop,” she says. “I can use it. Humans have more sensory awareness than just retinas, including something deeper and wonderful that feels like being hooked up to a larger life force. Even incapacitated, we are still part of this wonderful thing called life.”

Healthcare of the future

Monash’s Design Health Collab utilises a people-centred design approach to understand and activate significant, high-impact services and products for the complex health services ecosystem.

Current research focuses on five key areas –medical device design, behaviour change, healthcare experience, digital health, and healthy living – and includes investigations into the design of emergency department waiting rooms, prototype headgear for the Gennaris bionic eye, and a micro CT scanner for use in ambulances.