Professor Sue Davis, AO, is a pioneer and leading expert in women’s health in Australia, which is why she has the letters after her name – an Officer of the Order of Australia, awarded last year.

Her many achievements as an endocrinologist (hormonal medicine) and specialist in menopause are listed here; she’s been a Professor of Women’s Health at Monash University’s School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine for nearly two decades.

Professor Davis has been a longstanding, outspoken advocate for advancing women’s health, and isn’t about to stop, especially with a Victorian state election looming.

Her current concern is the availability of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to women with early menopause, and the lip service she says state and federal governments give to aspects of women’s health.

About 4% of Australian women experience premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) or complete loss of ovarian function before the age of 40, and 10% experience early menopause before the age of 45.

Yet many aren’t treated properly because they either think they don’t need it or their doctors don’t know how to treat it appropriately, she says.

Professor Davis spoke to Lens about menopause and politics.

We’re in an election week, and the Victorian premier has announced he’ll spend $70 million or so on women’s health, including clinics to treat menopause. That must be good?

There are simply not enough healthcare providers sufficiently experienced in disorders of menstruation and menopause to provide the proposed “comprehensive care” in 20 new women's health clinics.

Not only would these clinics need a newly skilled workforce to provide the promised care, but the upskilling would need to extend to GPs and pharmacists so that they can recognise conditions and know when to refer, and specialist endocrinologists and gynaecologists who’ll be called upon to provide expert advice. Women need appropriately trained healthcare providers, not bricks and mortar.

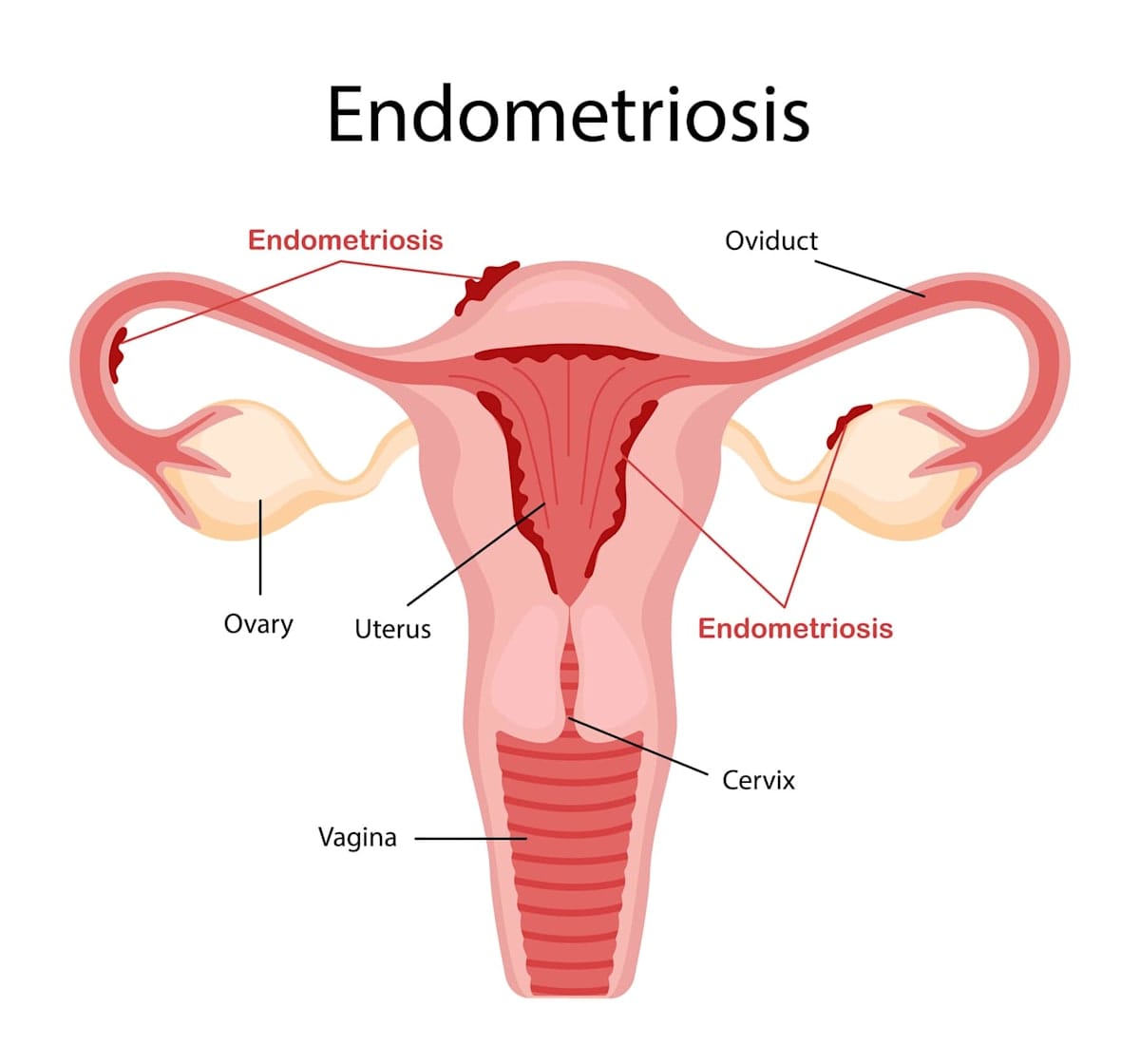

But they’re specifically talking about upgrading care of menopause, endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome?

There’s still a dire need for an accessible clinical service that provides care for women experiencing disorders of menstruation and menopause.

While endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome get a lot of air-time, such a service requires healthcare providers skilled in the full spectrum of gender-specific issues, including menstrual migraine, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and the array of conditions that cause irregular menstruation, as well as the nuances of menopause-related care.

Presently, there are few public clinics, except the women's clinic at Alfred Health, and the menopause clinics at Monash Health and the Royal Women's Hospital, that offer these services and, as part of healthcare delivery, train doctors to deliver the required care.

OK. Has New South Wales done a similar thing – put $40m into women’s health ‘hubs?’

These things are very political, and so you really need somebody in government to champion a particular cause. You could equally ask, why did the previous federal health minister promise $58 million for endometriosis this year? Why didn't he promise $58 million for midlife women's health instead? Because somebody got in his ear about endometriosis and influenced him.

Read more: Pause for thought: Taking the lead in women’s mental health

I mean, often these decisions are about who talks up the cause. There are some decisions that are clearly national health priority issues like, say, obesity or diabetes, but with many other conditions it's really who yells the loudest, and it's not often about what's needed.

A politician said, ‘We're going to give $40 million, and we're going to improve menopause.’ Now, after they've done that, they're trying to put together a committee to work out how to spend it.

You’re researching early menopause at the moment. What are you learning?

We’re doing a study of young women with early menopause, and there’s universal agreement that when women go through menopause early, before the age of 45, this is different to natural menopause. It’s a hormone-deficient state, just like somebody having an underactive thyroid.

Ninety percent of women under 45 have their ovaries working, but then there’s this 10% who don’t, and we know that if you don’t give oestrogen to these women, they have an increased risk of premature fractures, early heart disease, and premature death – every study shows that.

Yet, when we were recruiting women for the study, we found that most were not on hormone therapy, and doctors are telling these young women they don't need it.

This is dangerous. I mean, a 50-year-old woman with a few hot flushes is one thing, but a 40-year-old who’s not getting appropriate therapy, by the time they're 55 to 60, they're starting to get fractures and they are at risk of heart disease. These women are desperately under-treated.

And there’s a reluctance for doctors to get these women on HRT because of the controversies around it?

It’s been known for some time that HRT slightly elevates the risk of breast cancer, but it ‘s over-exaggerated, and there are some in the medical community who don’t understand that early menopause really is a serious condition, and the data shows that women who get proper, modern hormone replacement therapy have about a 40% reduction in all-cause mortality.

While there’s extensive controversy about HRT in older age, there’s none at this age.

What would be the ideal set-up for sufferers of early menopause in a city like Melbourne, then?

The GP should listen to your story, ask about your menstrual pattern, ask about your other symptoms and then do some blood tests, because with younger women, you've got to exclude other causes.

If it's identified as being early menopause, the doctor will then educate the patient about what this means for them. If it's somebody who hasn’t had children, we'd give them some counselling, because it's pretty devastating if you were hoping to have children – say you're 36 or something, you need to be informed of a diagnosis with clarity.

Read more: ‘It changed who I felt I was. Women tell of devastation at early menopause diagnosis

You want to be able to understand the diagnosis and the health consequences, and then be provided with all the information about hormone therapy, which at this age, unless there's a contraindication like breast cancer, every woman should be prescribed.

You should have a bone density and a cardiovascular risk assessment, and you should have an assessment for a potential cause. Is it serious? Is it autoimmune? Could you also have thyroid disease? Is it genetic? A sensible GP should be able to manage this.

What about menopause and the workplace?

I’d like to see a really high-quality study of women in the workplace. I went to ANZ and met some very young, slick executive women, probably six years ago, and they were very polite to me, but they weren't interested in women in the workplace and menopause, women's mid-life health, young women's health.

I bet if you went and spoke to them now, I don't know if they'd fund anything, but I think there'd be a greater awareness that we need to be talking about it.

Then we started a study, which was funded by Bupa. It was in its infancy, and while we were able to show that women with severe menopausal symptoms had lower self-reported work performance, we didn't realise that we should have been asking the questions about women who weren't working. Was there a reason they'd left work, or were not choosing to work?

Read more: Upping the ante to tackle early-onset menopause

What do you think are the answers to those questions?

I don't know. I'm concerned that menopause in the workplace is being over-emphasised and that it’s not the primary reason women are not working, and that there might be some over-embellishment.

There’s a whole debate bubbling and brewing around this. It’s a big deal in the UK now. It's gradually spilling across here, but people are making these claims about the impact of menopause in the workplace, and it's based on very poor-quality data.

I don't know the answer, because we haven't looked at it across the dimensions of work. Is it different for a cleaner versus somebody who's a senior executive? Are women in high, low and mid positions at work and who can’t function because of their symptoms the exception or the rule? I don’t know.