In 2016, Lynne Kelly published The Memory Code, a book based on her PhD research into Indigenous memory techniques, and how they might unlock the secrets of ancient sites established by oral cultures, such as Stonehenge and the Nazca Lines in Peru.

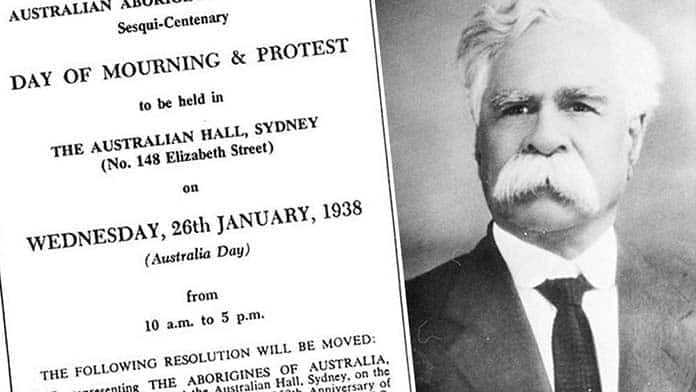

Kelly was influenced by her investigations into Australian Aboriginal People, who encoded information about plants, animals and creation stories into the songlines – navigation and teaching tools that linked important places such as sacred sites and waterholes.

The songlines allowed a vast and complex web of knowledge to be accurately transmitted for thousands of generations.

When neuroscientist David Reser read The Memory Code, he wasn’t thinking about how to help medical students remember the bones in the wrist or the ligaments around the knee.

“The book was interesting, but it really wasn’t anything that I was paying much attention to,” he says.

Read more: Connection to Country: Teaching science from an Indigenous perspective

That’s until he started talking to Indigenous educator Tyson Yunkaporta. The two men had been wanting to introduce more cultural elements into the Indigenous health units that form part of the Monash medical degree course.

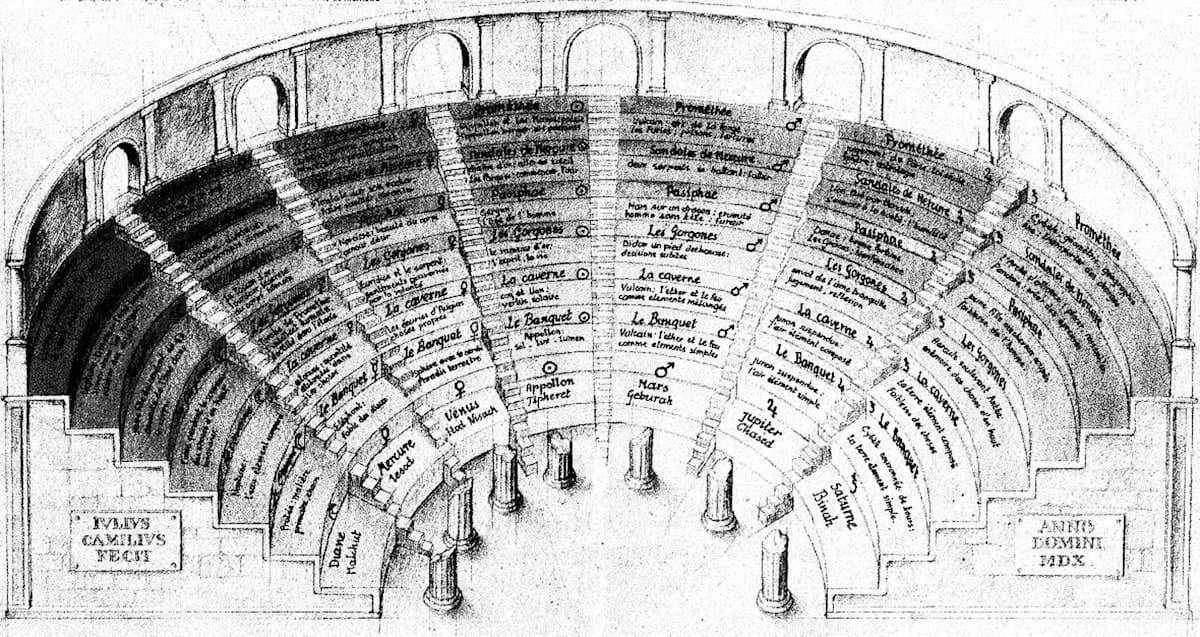

Dr Reser observed that the Indigenous technique described by Dr Kelly was similar to the method of loci, or memory palace method used by the ancient Greeks and Romans, and later by the Jesuits and other scholars.

The main difference is that the Aboriginal system involves walking around a landscape and attaching a story to each feature – the storytelling, combined with walking, are believed to aid the memory.

The memory palace in contrast involves creating a mental picture of a room (or palace), and attaching the items you want to remember to different locations.

The story of Simonides

The Hellenistic poet Simonides is credited – perhaps apocryphally – with inventing the technique. The story goes that Simonides was suddenly called outside while attending a banquet. During his absence the banqueting hall collapsed, crushing the guests beyond recognition. Simonides was able to reconstruct the guest list by remembering where they sat around the table.

“The problem with the memory palace is that it can be intimidating to get started,” Dr Reser says. “You have to construct it. You have to revisit it, and you have to pay careful attention to what you’re including and what you’re removing, or it becomes a lot less functional, maybe useless.”

Dr Yunkaporta and Dr Reser decided to compare the two techniques by asking 76 first-year medical students attending Monash’s Churchill campus to memorise a list of 20 common butterfly names.

The students were randomly divided into three groups – Dr Reser spent 20 minutes instructing one group in the memory palace method, asking the students to reconstruct their childhood bedroom.

Meanwhile, Dr Yunkaporta taught the Aboriginal technique, using a small garden on the campus. He walked the students around the space and told them a story linking the garden’s features – the students attached a butterfly name to each of the features as they walked. Their training time was also 20 minutes.

The third group was simply given the list and asked to memorise it in their own way.

All the students were tested at 10 minutes, and then 30 minutes.

Technique three times more successful

The students who used the Aboriginal technique were almost three times more likely to remember the entire list than they were before training, the researchers found.

The students using the memory palace were about twice as likely to get a perfect score after training, while the group left to its own devices improved by about 50% over their pre-training performance.

“We didn’t ask the students to remember the butterflies in any particular order,” Dr Reser says. “But when we went back and looked at the data, those students who used the Aboriginal method overwhelmingly were much more likely to remember the list of butterfly names in the sequence that they were presented.”

The results have been published in the journal PLOS One.

Importantly, a qualitative survey led by co-author Dr Margaret Simmons found the students using the Aboriginal technique said it was more enjoyable, “both as a way to remember facts, but also as a way to learn more about Aboriginal culture”, Dr Reser says.

It would be interesting to discover whether the technique could help other groups who want to improve their memories, he says.

“Like any fun, good research project, you get more questions than you answer from doing the study. Is this something that is teachable and applicable for other situations besides medical school? It’s something we’ve thought a lot about,” he says.

Read more: Why documenting Indigenous artefacts made from southeastern Australian trees is important

Dr Yunkaporta has since moved to Deakin University. Dr Reser and colleagues believe the technique should be taught by an Indigenous educator, so training has been suspended at Monash for now.

If Dr Reser was to repeat the experiment, he would make the test more challenging, he says. Medical students are highly capable, and their ability to remember a list of names – even without the benefit of a technique – was impressive, in his view.

A follow-up study was undertaken six weeks after the initial experiment, but only eight students participated – not enough to provide a meaningful result.

“But it did tell us that both techniques need to be practised. Otherwise, the information gets lost,” he says.