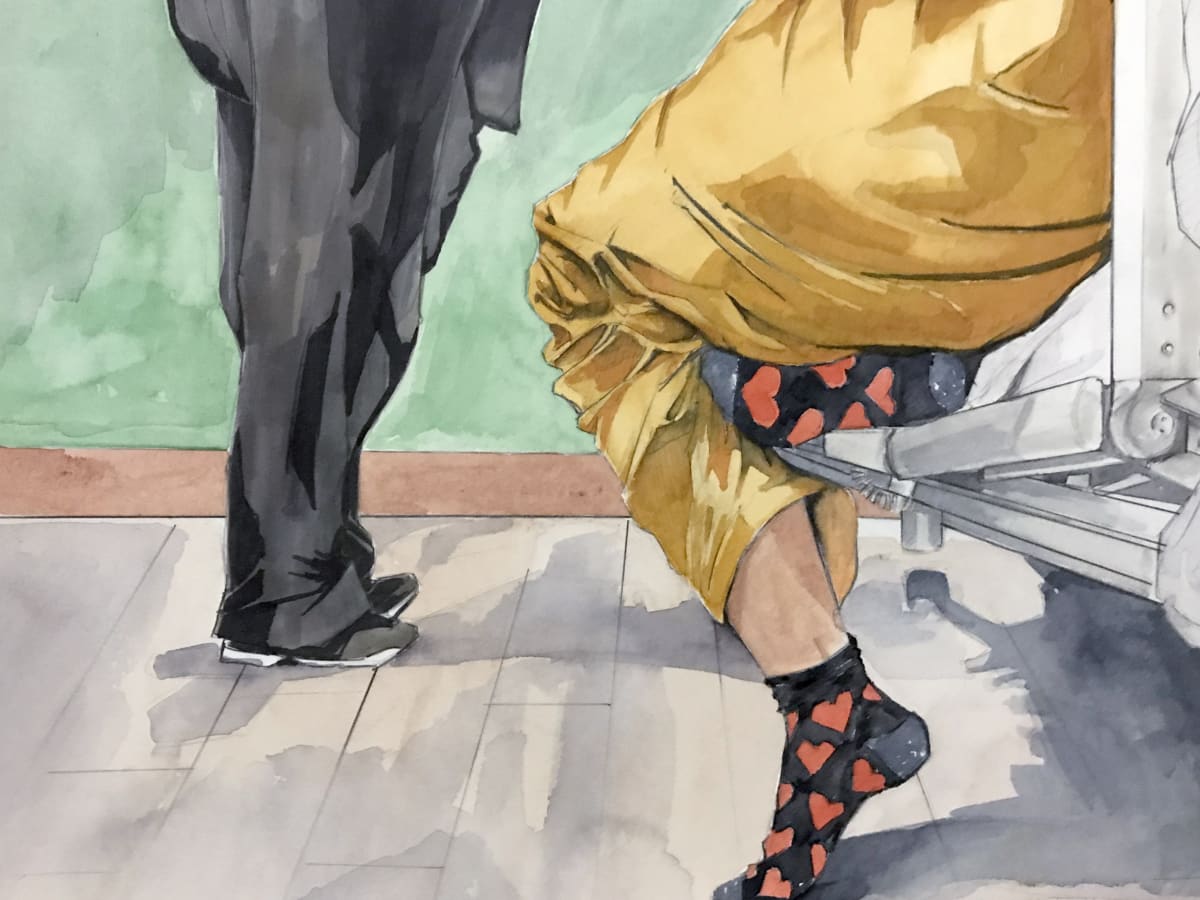

A picture speaks a thousand words – and Dr Nyein Chan Aung’s painting of the Melbourne hospital room says it all.

He was there for five nights, with his wife, Dr Thinn Thinn Khine, and her elderly mother, who was dying.

The room was a standard palliative care space at a major hospital – one bed and a couch. Dr Khine’s mother, Julia, as the patient, had the bed. Dr Khine had the couch, which left Dr Aung on the floor. There they stayed until Julia, aged 71, passed away after suffering a stroke.

The young doctors – childhood friends in Myanmar in the 1990s, and now married in Melbourne, with Thinn Thinn about to have their first child – are, in their words, “Monash family.”

Nyein is an industrial designer, lecturer and senior design research officer with Monash Art, Design and Architecture (MADA). He’s also an artist and inventor of “cool stuff”. Thinn Thinn is a geriatrician and endocrinologist with Monash Health.

Thinn Thinn’s family had come out to Australia for a visit when the stroke happened. This was in 2018.

The watercolour painting is titled By Her Side. Thinn Thinn’s mother was more to him than a mother-in-law. He was, he says, a troublesome young man back home in Yangon, and was written off by many as a bad seed. But not Julia, his English teacher, who recognised he had promise.

“She was one of the only teachers who thought I was worth something,” he says. “I didn’t know that I would marry her daughter one day, or cook her last meal, or be there as she was dying.”

In Burmese culture, when someone is dying, there’s always family or friends there with them overnight. The Australian model of largely institutionalised palliative care – in a hospital or aged care home; only the lucky, it seems, have an option of dying at home – is not always best geared towards a sense of togetherness, support, communal grieving, or even company.

The geriatrician and industrial designer were struck by this, which is what By Her Side, with its point-of-view from the hard hospital floor, reflects.

“One night she was quite unsettled,” says Thinn Thinn. “It was around 3am or 4am, and she needed extra medications. Nyein is on the floor – he could only see my legs and the nurse’s legs. He is a very nice man, and he gave me the couch to sleep on. But this was his view from the floor that night.”

A concept for better end-of-life care

Nyein writes, in an artist’s statement on the painting: “I have trained my entire life to observe, to receive and to reflect on images. They don’t ask for permission, and I don’t know how to reject them. The lights gave clarity to the moment, and the scene was burned into my memory. A week after Julia’s passing, I began painting this scene.”

Then, he writes, “a thought was born – I could use design to help create better end-of-life care”.

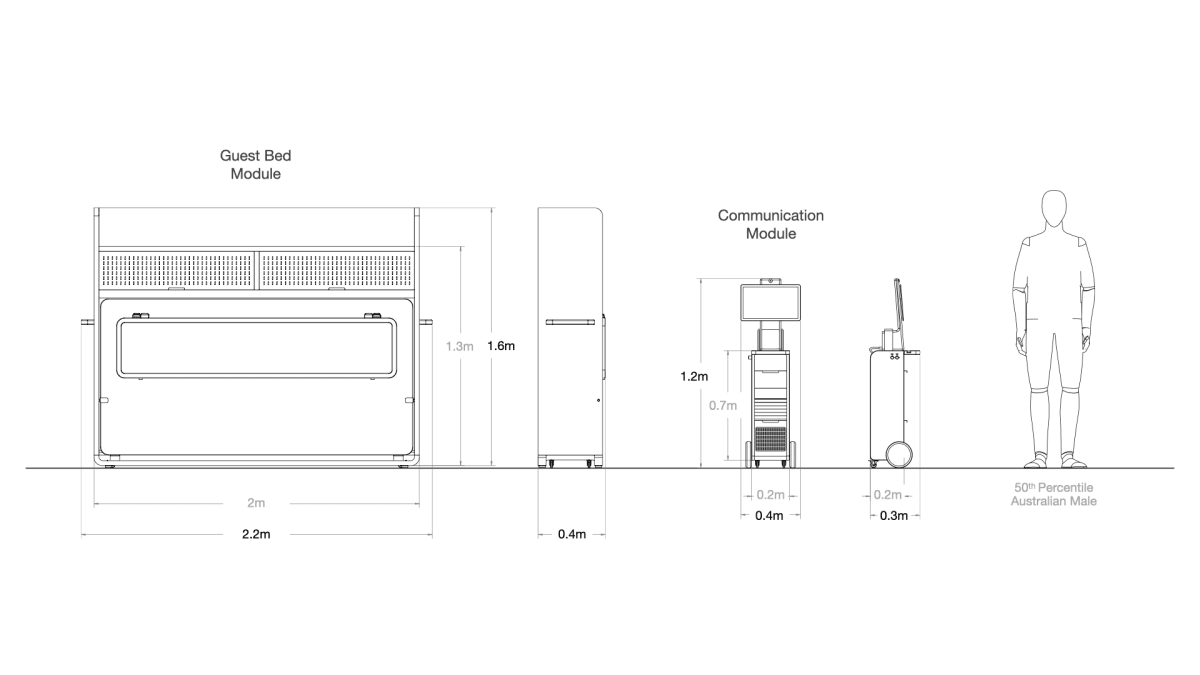

The concept is this: a fold-out bed and shelving unit, as well as a “communications” module, to easily convert a standard sub-acute hospital or aged care room into a palliative unit that enables a guest to sleep over.

The communications module – like a more sophisticated and user-friendly computer tray – enables full digital access, charging and storage.

“In our minds, we were asking ourselves, ‘Is there anything we could do, combining our expertise from clinical work and design…to see how design could change the patient and the family experience in end-of-life care?’,” Thinn Thinn says.

“Our goal is that at the end of this year we will have a functioning prototype built.”

Losing a loved one will always hurt, says Nyein. “I don’t think we can design or invent our way around that. But that pain doesn’t have to become trauma. That’s when design can be useful.”

The project has received funding, so far, from Creative Victoria and Monash University, and support from Monash mentors Professor Barbara Workman and Dr Hanmei Pan.

Nyein has an award-winning background in designing things that improve user comfort, including a patent-pending aircraft cabin that helps economy-class passengers sleep better.

“When a patient is not able to go home for their final days,” says Dr Workman, “and palliative care needs to be delivered in hospital, an acute or sub-acute space [hospital room] is often used, as palliative care services are limited.”

Conceptual platforms for the project include:

- Supply and demand. The demand for palliative care spaces far exceeds supply in Australia.

- A pattern of individual “slow decline” in an ageing population, often involving cognitive decline, or dementia.

- Meeting the needs of the patient in terms of incorporating items from home, facilities for family and friends, privacy, lighting, noise and exposure to nature.

Connecting the dots

“Our question,” says Thinn Thinn, “is how do we connect all the dots? We know from the data that the majority of the population want to die at home or close to home, but people are still dying in hospital because dying at home is still a huge task.

“As clinicians, we have these thoughts in our mind when we are interacting with patients, but we have no idea how to turn this into an actual product or design, or something to touch and hold. So we are very fortunate to be able to collaborate with an industrial designer, Nyein, who is, fortunately, my husband.

“When I am dying, something I would want might be quite different to what you would like. How do we define those things?

“The top hit is a home-like space. A lot of people say, ‘Even if I couldn’t die at home, I would at least like to be in an environment that is familiar to me and be surrounded by people I love, family or friends, and things that remind them of themselves.”

One idea central to the project is that of the patient’s world becoming progressively smaller. It shrinks from a large world in which they can travel and move, to smaller and smaller versions through home, then just bed.

“How can we connect design and medicine together to make this experience so much better?” Thinn Thinn asks.

In terms of shelf space, Nyein cites studies that have shown a palliative patient wants, on average, 5.5 personal items with them as they die – photographs, objects and heirlooms, for example, all of which remind the patient of their life. “Not necessarily functional things,” he says, “but things with emotional significance.”

Module offers 'virtual togetherness'

The communication module, meanwhile, is an acknowledgement of the digital age. “It would offer virtual togetherness,” Nyein says.

The unit would both charge and display screens with a moving camera. “Our ideas of family and togetherness are really changing from one generation to the next,” he says. “There are some of us who have a different relationship with the world, and we are in no place to judge if someone’s primary idea of togetherness exists virtually.

“The current mode is, ‘Here’s the hospital, here’s the room, it is all set up.’ We want to challenge this idea.”