We welcomed 2020 with no vision of what was to come – no one knew it would include the coronavirus pandemic. But with the COVID-19 crisis came contagious anxieties around the seemingly endless unknowns: What if I lose my job? How do I manage my business? What if I lose someone I love? How long will this last, and who do I trust?

In this way, tolerating uncertainty suddenly became a universal struggle; never more so than within the healthcare environment.

- Who and how are people infected?

- How do we diagnose and treat this virus?

- What are the short-term and long-term impacts of the sick?

- Will there be a vaccine, and if so, when?

Healthcare teams now rely on the critical skill of managing this uncertainty as they try to develop a timely, systematic and collaborative healthcare response to the growing number of Victorians who will require hospitalisation and intensive care treatment in the coming weeks.

But uncertainty in healthcare isn't a new concept, and can be traced to the founders of modern medicine and nursing in the mid-1800s. Canadian Physician William Osler famously said: “Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probably”. And Florence Nightingale wrote in her nursing notes that “apprehension, uncertainty, waiting, expectation, fear of surprise, do a patient more harm than any exertion”.

While the media and television programs often portray medicine as solely “facts” and “knowns”, quality medicine is always changing and improving with new information. Patients themselves respond to treatments differently, or present differently, particularly when it comes to COVID-19 symptoms. Together, this means that medicine is inherently and intrinsically integrated with uncertainty.

This concept was starkly illustrated on the recent Four Corners episode "Inside Italy’s COVID War", which showed the raw reality confronting frontline healthcare workers – Italian doctors and nurses, faced with unimaginable decisions about who received life-saving treatment and who didn’t, where a “right” answer didn’t exist, but still required answering.

Indecisiveness and avoidance when faced with these ambiguous healthcare situations would actually cost lives by delaying the decisions necessary to save them.

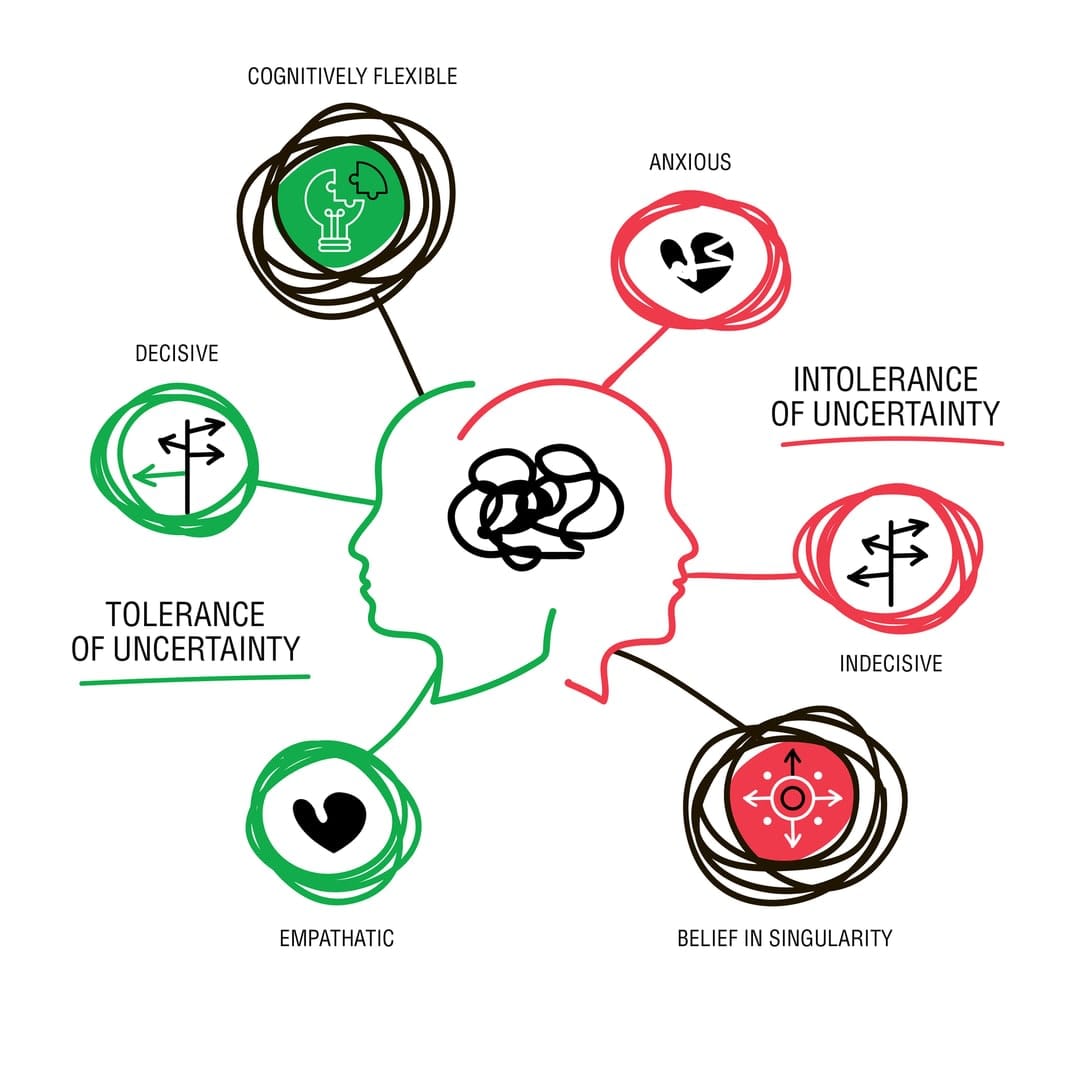

This ability for healthcare professionals to take judicious and decisive action regarding patient care despite there being no clear or right answer (often due to conflicting, ambiguous or unknown information) is an essential workplace skill known as tolerance of uncertainty.

Why is tolerance of uncertainty important?

Research shows that healthcare professionals with lower tolerance of uncertainty burn out, and their actions negatively affect patient care. This is likely because these providers waste time, money and resources in futile attempts to minimise implicit healthcare uncertainties and unknowns. Conversely, healthcare professionals with higher uncertainty tolerance are likely more cognitively flexible, resilient, and demonstrate empathy by involving patients in their own care, as they accept that decisions and actions must be taken even when there are limits to what is “known”.

Despite tolerance of uncertainty being critical for improving healthcare outcomes, we typically select healthcare students based on how applicants perform on answering assessments “correctly” – even though evidence illustrates that interviews may be more valuable than single-answer, multiple-choice tests. What does this mean for the future healthcare workforce in these uncertain times? Are we selecting the right students into healthcare? Can we help students develop a tolerance of uncertainty through our teaching practices?

Can we teach it?

While some thought that tolerance of uncertainty was an unchanging personality trait (that is, nature), we now have evidence that shows healthcare education can either hinder or foster students’ uncertainty tolerance (that is, nurture).

An interdisciplinary research team at Monash University received funding to explore how, and to what extent, higher education teaching practices foster and/or hinder learners’ uncertainty tolerance both in the classroom and in the workplace. Preliminary research coming from this grant suggests that how we teach plays a more significant role in students’ uncertainty tolerance than was once thought.

While extensive oversight, policies and over-prescriptive educational guidelines (such as teaching that favours "least resistance" learning) stop students from tolerating uncertainty, there are practical classroom approaches that help enhance students’ tolerance of uncertainty. These include opportunities to practise “uncertainty” using low-stakes unknowns. These include:

- exposure to diversity (for example, diverse teamwork)

- providing case-based learning activities without clear answers (for example, future-focused problems such as a pandemic or climate change)

- “pedagogical bombing”, where a solved problem is thrown a spanner.

Through these teaching practices, educators can actually help students develop the critical skillset necessary to tolerate uncertainty. Students who transform through this classroom “discomfort” become solution-focused, cognitively flexible, and prepared for "real-world" uncertainties such as those facing the frontline healthcare workers today.

The pandemic has highlighted the need for higher education to invest in our healthcare students now by engaging in future-focused educational practices that will equip the next generation of healthcare professionals with the critical skills and capabilities needed to effectively function in the unknown, and lead us through these uncertain times.

This research is funded through Monash Education Academy.