In Australia last year, 1123 people died from opioids – illicit drugs such as heroin, and pain relievers such as codeine, oxycodone and morphine. If used regularly, physical and psychological dependence can develop.

In recent years most deaths have been due to pharmaceutical opioids – that is, overdoses of strong pain medicines – though heroin-related deaths are increasing rapidly, so we need evidence-based responses for both.

One key approach to reducing these deaths is treatment for opioid dependence. Although the evidence shows treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine are effective, people who are dependent on opioids continue to face barriers to accessing them.

These include cost, stigma, restrictiveness of the treatment regime, and a lack of places to go to receive treatment.

Read more: Weekly Dose: Naloxone, how to save a life from opioid overdose

Opioid dependence treatment

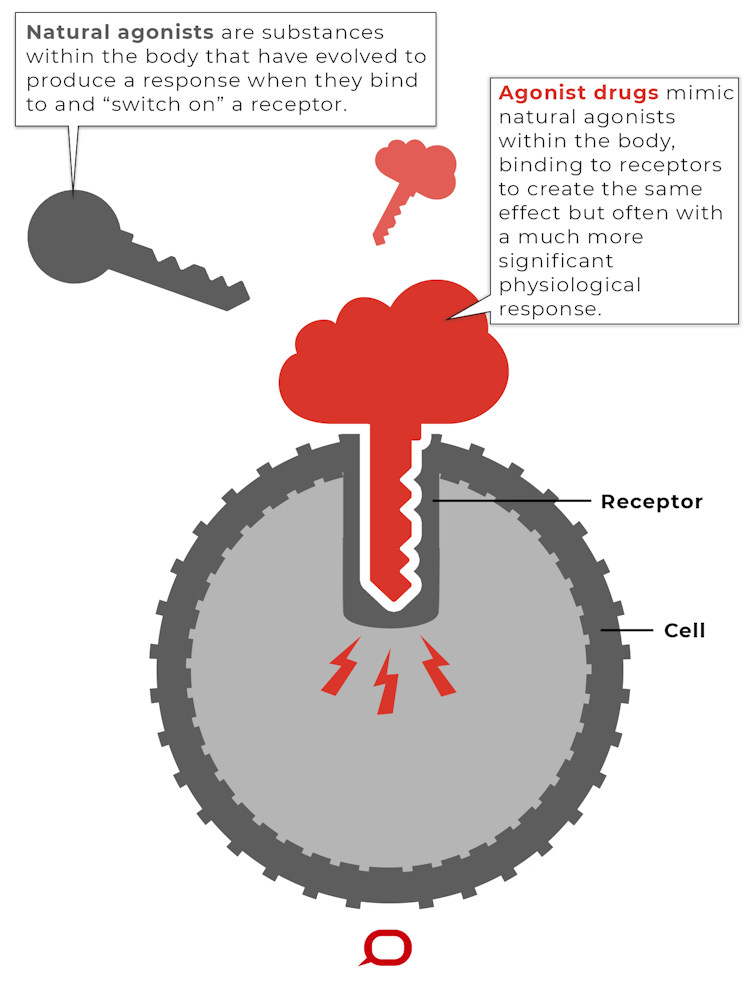

The dependence treatment backed by the strongest evidence is called “opioid agonist treatment”. An opioid “agonist” means a drug that produces opioid effects in the body.

Opioid agonist treatment is when a known and legal opioid medicine (the opioid “agonist”) is provided in a therapeutic setting, like a clinic or pharmacy, in a regular dose. This removes the need for using additional opioids by reducing craving and withdrawal.

Staying in treatment longer is associated with better outcomes, with best results seen when treatment is continued for 12 months or more. So this is a longer-term treatment providing an opportunity to make sustainable changes, as opposed to a short-term detox.

The two most common medicines used in Australia are methadone and buprenorphine. Both are available through general practitioners and community pharmacies, as well as specialist clinics. Newer forms such as long-acting buprenorphine have also recently entered the market.

Methadone is what we call a “full opioid agonist”. It mimics the effects of other opioids, such as codeine or morphine, and it can remove the need to take other opioids by preventing opioid withdrawal and craving. Taken in daily oral doses methadone does not produce euphoria, or a “high”. At higher doses, methadone also blocks the effects of other opioids, helping to prevent return to other opioid use.

Buprenorphine (often provided in combination with naloxone, a medicine used to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose) is referred to as a “partial opioid agonist”. It’s less sedating and, unlike methadone and other opioids, is less likely to cause breathing difficulties and overdose.

Treatment is effective

High-quality evidence shows these treatments work. They help reduce opioid use, improve health, prevent the spread of blood borne viruses by reducing the likelihood people continue to inject, are cost effective, and reduce crime.

The most profound effects of these treatments is their ability to save lives. Risk of death while in treatment is substantially reduced, by around half compared to when a person is dependent on opioids and not receiving treatment.

These treatments have been shown to work just as well for people who develop dependence to prescribed opioids and people who use heroin.

In 2005 the World Health Organisation put methadone and buprenorphine on their list of essential medicines, recognising their importance in treating opioid dependence.

So it might be surprising to learn many people in Australia who could benefit from these treatments choose not to use them, or are not able to access them.

Four barriers to treatment

Cost

Opioid agonist treatments attract some subsidies, but their dispensing fees are not covered by Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, which subsidises prescription drugs. Where treatment usually adds up to A$35-A$70 a week, cost can be a key barrier to access.

Stigma

Some people choose not to access these treatments because they see them as being for people who use heroin, or don’t want to attend services seen as being for people who use illicit drugs. Other people believe these treatments are just replacing one opioid with another, and are not aware of their strong scientific support.

Restrictiveness of the treatment regime

The need to attend a pharmacy daily for dosing at the start of treatment can affect work, study or family commitments.

Nowhere to go

Finally, treatment access is limited in some regions because there are not enough GPs who prescribe these treatments. This is despite a change from many state governments in recent years to reduce barriers to prescribing.

In Victoria and New South Wales, for example, all GPs can prescribe buprenorphine treatment without additional training. Nonetheless, prescriber numbers have been slow to increase, with some GPs remaining hesitant to offer these treatments.

People turning to short-term treatments instead

As a result of these barriers, many people who are dependent on opioids choose not to seek help, or are not able to access the treatment they need.

Some choose to access shorter-term treatments such as a “detox”, where over the course of seven to ten days they cease opioids while their withdrawal symptoms are treated with medications.

This is concerning because the rates of relapse from short-term treatment are high, and research shows the risk of non-fatal or fatal opioid overdose increases following short-term treatment. This means these short-term treatments contribute to opioid-related deaths rather than preventing them.

To stem the loss of life from opioid use in Australia, it’s critical we break down the barriers to the opioid dependence treatments we know are most effective.

Read more: Here's what happened when codeine was made prescription only. No, the sky didn't fall in

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.