Almost two-thirds of Australians are obese or overweight. What can we do about obesity and all its associated chronic health problems?

Obesity is stigmatised, and I think we put too much emphasis on patient lifestyle change. In Australia, obesity isn’t classified as a disease, but rather is considered a lifestyle choice. The stigma is that obesity is due to sloth and gluttony, and that stigma produces an incorrect impression that an obese person will avail themselves of medication in order to eat an extra hamburger rather than use the medication to lose weight.

I completely disagree with that premise, but it persists in our society. We have assigned a moral value to obesity.

Why is obesity stigmatised?

It’s our societal response. Just go back 200 years, and Rubenesque [voluptuous] ideals were a virtue. So, it’s an evolving ideal. Naomi Wolf [The Beauty Myth] had a lot to say on that, and I buy her argument – we’ve assigned a value of beauty to skinny-ness in this era, but that may well change. There’s a socioeconomic value to it, too, now – to pursue that weight ideal requires investment.

It’s very hard to be that skinny without putting resources towards it. Bad food is cheap, delicious and plentiful. It‘s hard to eat bad food and not gain weight. But to pursue these idealised figures requires time at the gym, time exercising, and money.

We’re seeing a growth in cosmetic surgery for young men now to achieve idealised physiques, we’re seeing a growth in steroid abuse in young men. It’s only becoming more prevalent.

Do perceptions of obesity change depending on how old someone is?

Yes. That’s an interesting point. We view low body weight as healthy through youth, young adulthood and middle age, but you reach a point after 70 or 75 years old where low body weight is a health risk. The expression “skinny old lady” speaks to frailty for a reason, because we recognise that old people who are very thin are very frail. Their bones are weaker, they have less muscle, whereas the stout old grandma conjures visions of health. And it’s probably true, because chubby old people have a better health prognosis.

The frail old lady is the one you worry about. I’m only talking about women here, because those are the stereotypes we most resonate with, but the same is true with men. Older people do better being a little bit fat.

Middle age is the danger zone for obesity and all the related health problems. Are men more at risk than women?

No. Women are protected from heart disease pre-menopause, but post-menopause their rates are higher. After menopause, their rates climb much higher to reach parity with men.

We think of men as the ones who suffer from cardiovascular disease the most, because it’s most clear in them, and there’s not the same inflection point with risk – it’s just the same evolving risk with time. But the disease risk is higher in post-menopausal women.

Why is heart disease risk higher in post-menopausal women?

The basic issue is that in men steroid levels decline progressively. Testosterone goes down with time. Some have called this the andropause, the male equivalent of menopause. But it doesn’t happen in the same way menopause happens in women.

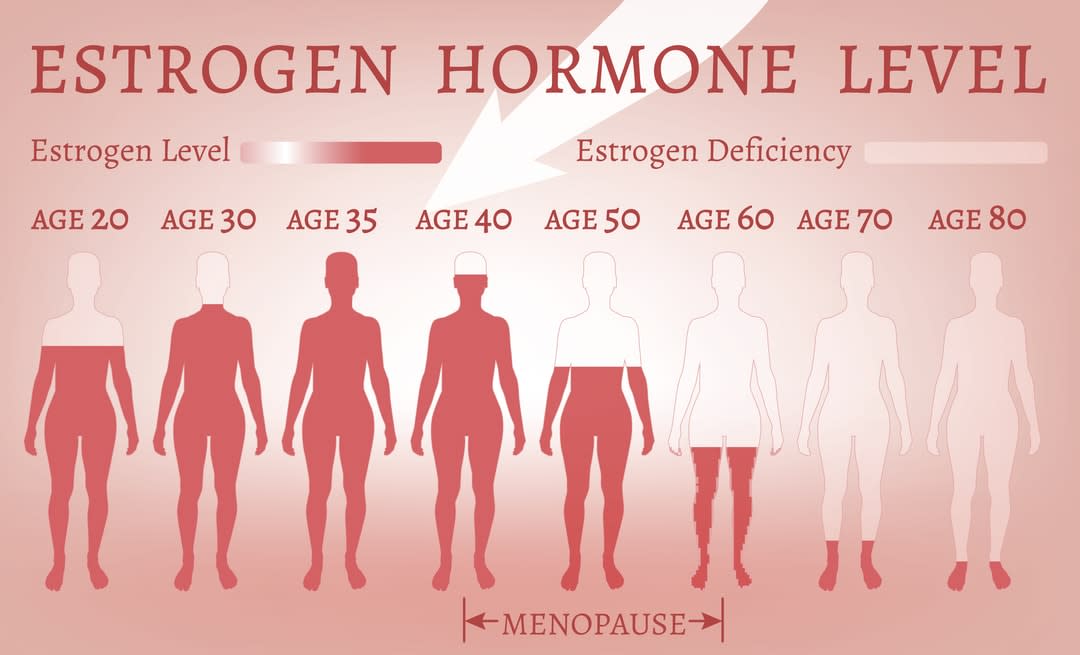

In men, it’s a long, slow decline, from around the age of 35 on. In women, steroid levels, or estrogen, keep fluctuating around their ovarian cycle until they run out of eggs – menopause – and then the estrogen declines precipitously. That’s the major difference. Both hormones have powerful metabolic benefits.

Testosterone builds stronger bone and muscle, and helps endurance and strength, whereas estrogen has a variety of effects, one of which is weight gain prevention. It helps women burn energy in ways we don’t fully understand.

So when estrogen runs out, a woman is at high risk of getting fat?

Yes, exactly. If a woman doesn’t change anything about her lifestyle after menopause, she’ll have a higher chance of becoming obese, because estrogen is not there helping burn extra energy.

Meaning a woman has to work harder to maintain a healthy weight?

Yes. Delicious bad food is aggressively marketed, and we live in a world where it’s easier and easier to do less and less. You can go for days without doing anything physical. It becomes more acute, because things might have been in balance for this woman, her weight might have been stable for years. But with a hormonal change over which she has no control, there’s a dramatic shift in the balance.

So does that mean that post-menopausal women have a high risk of heart disease like middle-aged men?

Yes. Heart disease rates achieve the same level as men in women post-menopause. Women catch up quickly. This is when hormone replacement therapies (HRTs) are recommended for some women. The caveat, though, is that estrogen and testosterone also drive cancers – in men they drive prostate cancer, and in women breast and ovarian cancer. We still don’t know the safest way to restore ovarian hormones to a woman without increasing her disease risk.

In general, is it correct to say obesity is due to genetics and behaviour?

Exercising more and eating less remains relevant. If an obese person loses five per cent of their bodyweight, they’ll achieve disproportionate metabolic benefits. Their disease risk will decline much more than you would anticipate from a modest weight loss. Modest weight loss is a strong health benefit. Around 20 per cent of people who make a lifestyle change to lose weight can keep the weight off for a long time.

And the genes?

We don’t know all the genes involved in body weight; we think we know about five per cent of them. There’s a lot out there we don’t understand, but it’s pretty clear (from pre-clinical settings) there’s a strong genetic component. Identical twins have a high concordance of body weight. Twins raised apart have a high concordance of body weight, if they’re identical. If they aren’t identical they have a lower concordance of body weight – about 30 per cent lower.

Genetically identical twins have about a 70 per cent concordance of body weight. We still attribute obesity to personal choice, but it’s abundantly clear that different people have different capacities to modify their risk.

It’s only when we accept something as a disease that we can properly engage with patients and properly treat them.

It’s only when we accept something as a disease that we can properly engage with patients and properly treat them. The metaphor I use is that of mental illness. Twenty-five years ago, depression was still a condition between you and your priest – it was considered a moral disease.

Since then, we’ve got a much better understanding of the biological basis of depression, and we’ve developed far more effective therapies for it. We’ve destigmatised depression and taken the moral element out. But the moral element still exists in obesity. You see a fat person eating a donut and you make a moral judgment.