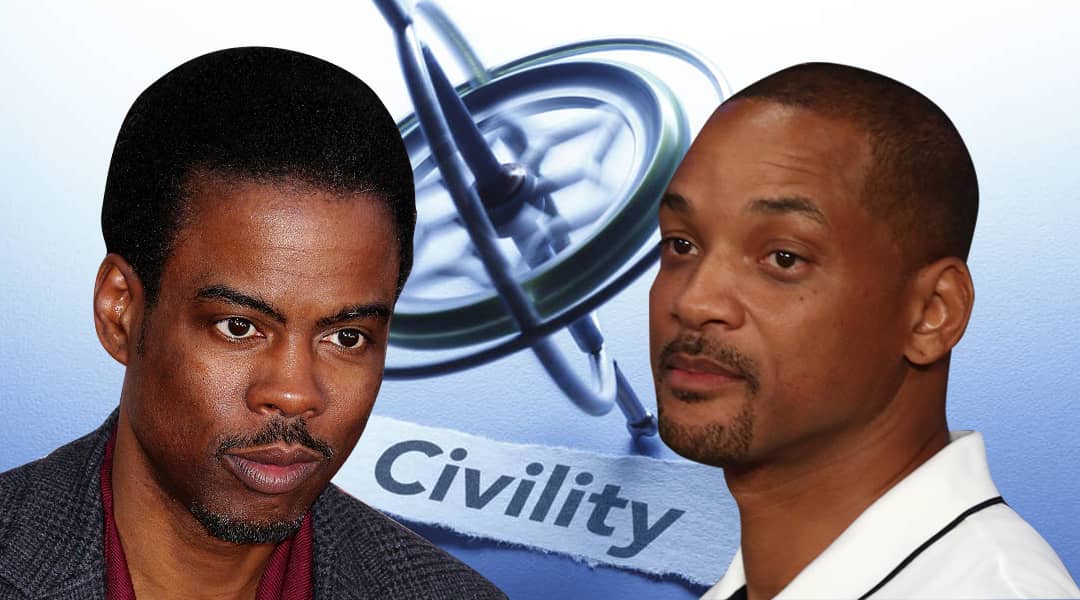

At this week’s recent Oscars ceremony, actor Will Smith slapped presenter Chris Rock after the latter made a joke about Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett Smith. The incident unsurprisingly elicited much public debate, with many condemning both Rock’s sexist joke and Smith’s violent reaction.

In an interesting contribution to this debate, Sydney comedian Béa Barbeau-Scurla pointed out that one of the key problems with jokes like Rock’s is that there is generally an expectation that women – or members of other vulnerable and oppressed groups who may also be the targets of these jokes – react to them by smiling because this is the polite thing to do.

Yet, Barbeau-Scurla argued, when people react to these kinds of jokes by smiling:

“… they’re just trying to be polite for the sake of being polite … For so many years women, queer people, people of colour, go through life smiling at these micro-aggressions because it’s easier that way, but action and conversation only really comes from not responding politely.”

Barbeau-Scurla’s observation raises important questions regarding the role of politeness and, more generally, civility in our society.

- Is it always appropriate to be civil?

- Can incivility sometimes be more desirable than civility?

What is civility?

To address this important question, we first need to understand what civility is. Civility is an aspirational concept, consisting of three key dimensions: civility as politeness, moral civility, and justificatory civility.

The most common way in which we think of civility is through the idea of politeness, which involves compliance with etiquette, protocol, and other norms of behaviour in order to facilitate peaceful living among people different from ourselves. Civility as politeness serves as a social lubricant that sends signals to other people to facilitate cooperation in society, and reduce the chance of conflict.

Moral civility is much deeper than civility as politeness. It involves not simply abiding by norms of etiquette, protocols, and good manners but, more fundamentally, displaying a commitment to respecting our fellow citizens as free and equal persons, by refraining from using forms of speech and behaviour such as hate speech, violence and discrimination. When we’re morally civil, we communicate to others that we respect them as free and equal members of society.

Justificatory civility is often overlooked during public debate about civility. Justificatory civility demands that we justify laws and policies by appealing to reasons that other members of our political community would accept. These should be reasons grounded not in sectarian interests or particular religious or ethical views, but in shared moral and political values tied to the common good.

Crisis 1: Campaigning to prevent domestic violence – A deficit of smiles

In some situations, failing to comply with norms of politeness, etiquette and decorum can contribute to fighting injustice.

A recent example is Grace Tame’s demeanour with Scott Morrison ahead of the Australian of the Year Awards. Tame and her fiancé deliberately refrained from smiling and being cordial.

While viewed as impolite by some, Tame arguably advanced the public conversation by behaving outside of expected norms of politeness. Her behaviour called into question some of the government actions and positions in responding to sexual violence.

Crisis 2: Ukraine – It’s not always necessary to be polite

In another recent example, about 100 diplomats from Western countries infringed on norms of politeness and walked out in protest during the speech of the Russian foreign minister at the United Nations Human Rights Council. This was an act that violated accepted international protocol, with the goal of signalling disagreement with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and condemnation of Russian aggression.

In both examples, it can be argued that the UN diplomats and Tame engaged in what Derek Edyvane refers to as incivility as dissent, where people challenge norms of civility as politeness to call attention to particular issues (such as violation of international law or violence against women).

These forms of dissenting incivility (as impoliteness) also help to challenge the “dark side” of civility – that is, the use of civility norms to preserve existing injustices and hierarchies of power (for example, patriarchy).

Crisis 3: Climate Change – Incivility when you’ve had enough

The climate change crisis constitutes the most significant challenge of our time. Frustration with the lack of government response to this crisis often manifests in ways that violate the norms of civility as politeness – such actions have been visible in Australia in public responses to the government during the 2019-20 bushfires and the most recent floods.

In such cases, displaying incivility as impoliteness by engaging in protests or refusing handshakes might be justified because decision-makers are not sufficiently responsive to challenges such as climate change.

Shared norms of politeness, moral civility and justificatory civility arguably help maintain peaceful coexistence between different ethnic, religious and cultural groups in contemporary diverse societies. But sometimes, incivility might be justified to spark change.

So, in the face of inappropriate jokes such as Rock's attempt at humour – which are themselves acts of incivility – do we grin and bear them out of politeness, or bare an open-handed slap, like Smith did?

Violence (also a form of incivility) is unacceptable, but civility, and when and how to enact it, is complicated. Sometimes it may be better to be impolite and not smile, if we want to promote change.

This article was co-authored with Yuqi Lin and Mark Yin, members of The Monash Centre for Youth Policy and Education Practice Youth Reference Group.