When Hitler was defeated and the concentration camps liberated, many survivors fled as far from the scene of their suffering as they were able to go.

That’s one explanation for how Melbourne, Australia, became home to the world’s largest population of Holocaust survivors outside of Israel: most of these post-war refugees were Yiddish speakers – they wrote books in Yiddish, attended Yiddish theatre, played Yiddish music.

Since WWII, the number of Yiddish speakers has fallen away. The UN says Yiddish is endangered, but researcher Margaret Taft believes it will live on.

“Languages evolve and move into different phases,” she says. “And there's been an incredible rebirth and re-interest in Yiddish. But we don't have the number of Yiddish speakers that we had.”

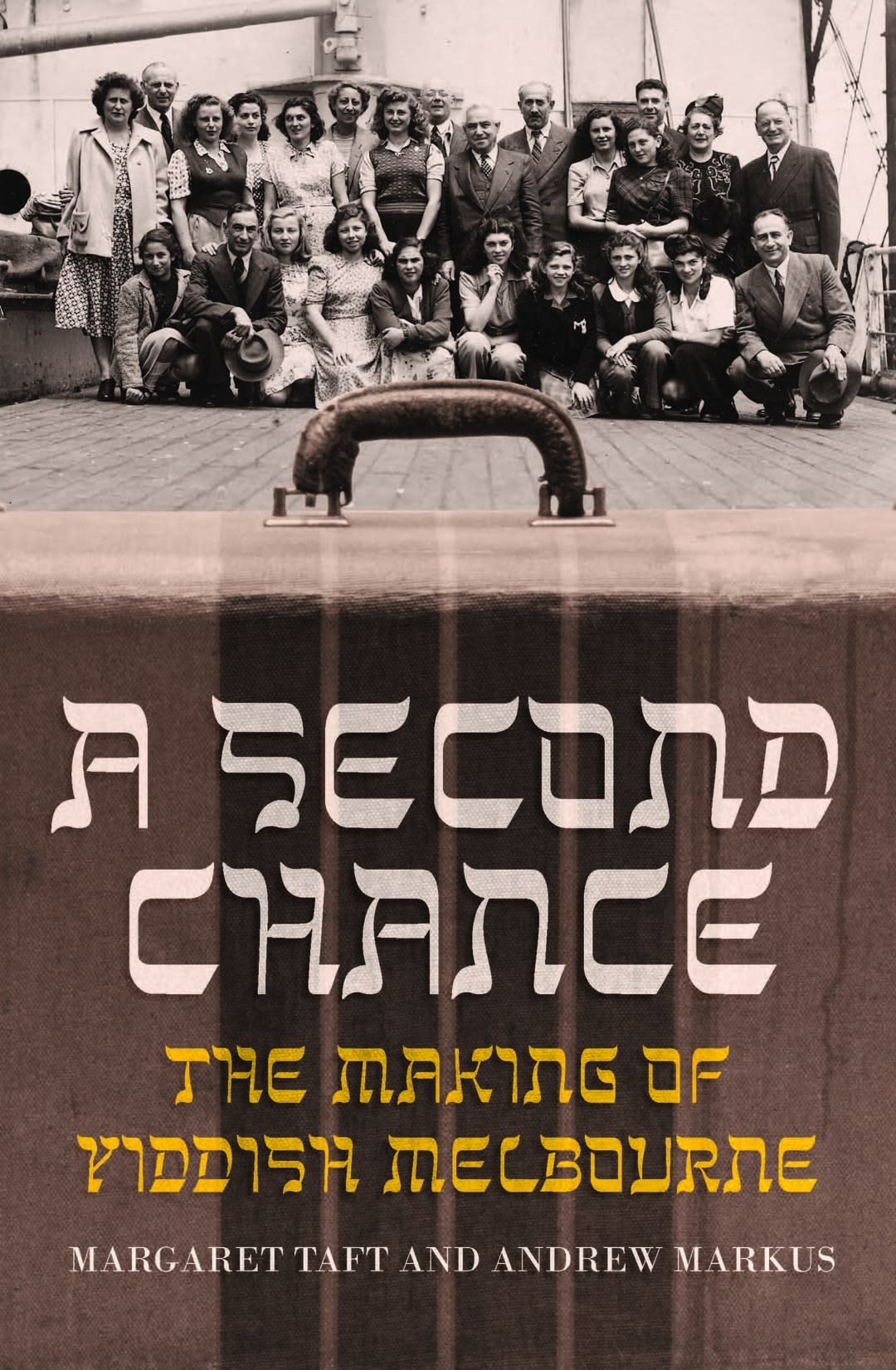

Dr Taft has spent more than a decade researching Yiddish Melbourne, which is the title of a website hosted by Monash University’s Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation. With Professor Andrew Markus, she's also written a book, A Second Chance: the Making of Yiddish Melbourne.

Before the Nazis sought to exterminate them, the Jewish population across Europe and elsewhere was estimated at 17 million, of which up to 13 million spoke Yiddish. Of the six million Jews who died in the Holocaust, 85 per cent were Yiddish speakers, and about three million were Polish Yiddish speakers.

When the post-war survivors left for Israel, North America and Australia, they continued speaking Yiddish, and their children learned it, too – but the language wasn't always passed on to the second and third generations.

Dr Taft, for example, learned Yiddish from her Polish-born parents, but her husband and children don't speak Yiddish. Sometimes her husband asks her to translate a Yiddish joke, and she finds herself at a loss – unable to put “the feeling” of the language into English.

“I think Yiddish has a heart and soul that transcends the vernacular, because it was a cultural identity,” she says. “It might be because it was a language that was born out of the struggle to survive – the people who spoke it endured such hardship because they were the wanderers. And wherever they went, they couldn't take much with them, but they could take their language. That was their identity.”

Yiddish Melbourne

Before WWII, Melbourne had Australia’s largest Jewish population, many of whom spoke Yiddish. When the US closed its doors to mass migration in the mid-1920s, a number of Jews who may have once headed to New York made a home in the inner-Melbourne suburbs of Carlton and Brunswick instead.

Dr Taft says these Jews were responsible for bringing Europe’s post-Holocaust refugees to Australia. At that time, strict immigration quotas were imposed in the US, but Australia was seeking to boost its population as quickly as it could – one million European immigrants settled here between 1945 and 1955. Of these, 1.8 per cent were Jews.

“About 17,300 post-war survivors came to Australia – they were either sponsored by relatives or friends or by Jewish welfare,” Dr Taft says.

Australia’s first immigration minister, Arthur Calwell, who coined the phrase “populate or perish”, agreed that Australia would accept refugees, but wanted to pick and choose.

“He excluded Jews from the program,” Dr Taft says. “In the end he only allowed about 250.”

The rest were sponsored by Melbourne’s Jews, who worked with international Jewish aid organisations, including some in the US. They raised money to pay for their passage, arranged housing for those who had no place to stay – 11 hostels were set up for the purpose – found them work, and paid for their medical care. This was necessary because the sponsored Jews were excluded from Australian welfare services for five years. The sad parallels with today’s asylum seekers aren't lost on Dr Taft.

Of the 20,000 Jewish people living in Melbourne in 1967, 14,000 were descended from Yiddish speakers.

Until 1955, post-war immigration forms asked new arrivals whether they were Jewish. Ten years after the war, all the post-Holocaust survivors had been settled, Dr Taft says, so the question ceased to be relevant.

Melbourne’s Jewish population doubled post-war, gradually relocating to Caulfield, Elsternwick and St Kilda. Of the 20,000 Jewish people living in Melbourne in 1967, 14,000 were descended from Yiddish speakers.

In Dr Taft’s view, nearly everybody speaks a little Yiddish – you probably know that a bagel is a bread roll with a hole in the centre, for instance, or what it means to shlep a bag around, or why a mentsh is better than a shmuck.

North American researchers refer to a surge in “post-vernacular Yiddish”. This is the Yiddish now being taught as a second language, perhaps to people whose parents or grandparents spoke Yiddish. Other aspects of Yiddish culture, such as Klezmer music, are also finding a new following, Dr Taft says, while comedy aficionados might argue that Yiddish humour has never gone out of style.

Some Melbourne institutions that were established to promote Yiddish have become cultural beacons. Elsternwick’s Sholem Aleichem college, a secular school, teaches Yiddish as a second language to primary school children. Kadimah, the Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, was established in Carlton in 1911. It has also moved to Elsternwick, (“Yiddish culture with chutzpah,” says the website), where it holds Yiddish conversation classes, and stages Yiddish theatre nights, cabaret, comedy, musical and literary events.

Yiddish is also taught and spoken within the ultra-Orthodox community – and their numbers are growing, in Australia and elsewhere. (About 3000 live in the Melbourne suburb of Ripponlea.)

In the last chapter of her book, Dr Taft quotes the Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978. In his Nobel acceptance speech, Singer said Yiddish “has not said its last word”.

“It contains treasures that have not been revealed to the eyes of the world. It was the tongue of martyrs and saints, of dreamers and cabalists – rich in humour and in memories that mankind may never forget.”