Our human brains respond to extremes, and our social lives abound with ways of standing out.

For Spinal Tap guitarist Nigel Tufnel, an amplifier that went to 10 wasn’t enough. Tufnel designed one that went to 11. For Italian heiress Marchesa Luisa Casati, showing up to a party with a nice frock wasn’t enough. Casati frocked up in live snakes, and arrived with a pair of cheetahs on leads.

Humans love to go to extremes, and when it comes to language, we're always on the lookout for new and exciting ways of turning it up to 11. Whether complaining, cussing, cajoling, abusing, deceiving, bullying, sweet-talking, persuading, dissuading, gossiping, praising, amusing, charming, seducing — in most walks of linguistic life, it’s usually in our interests to exaggerate. And you may call us "cheaters", but the fewer live snakes the better, we say!

But which words are fantabulous and which not so cool when it comes to embellishing language? And why do we cycle through extreme words more quickly than we cycle through daggy dad prime ministers? We’ve got a ripper of a groovy tale for you.

The shock and awe of terribly extreme words

A bit of imaginative embroidery is useful, of course — a good way of getting people to pay attention to what you’re saying. Take modern-day awesome. Search the internet for the word and you’ll find no end of headlines making jawsome (jaw-droppingly awesome) declarations.

How to Create Awesome Content!

Awesome Advice: Summer Self-Care For TIRED TEACHERS!

Awesome Performance of Dance Group!

Awesome Blog Writing Service!

25 Awesome Ways to Beat Holiday Exhaustion!

Awesome is a brand of linguistic extravagance dubbed “terrible emphasis”. It seems all around the world, humans enlist horrifying words for emphasis.

For English, you might compare the fate of words such as terrific (“terror-inducing”) or tremendous (“such as to excite trembling”). Awful, originally also “full of awe”, had the same gruesome beginnings but, like terrible, it never went that extra step in the positive direction.

Very different from their upbeat siblings "awesome" and "terrific", neither "awful" nor "terrible" can refer to something very good. Nonetheless, both words were pressed into service as general intensifiers to boost other expressions (more terrible emphasis). Rudyard Kipling regularly wrote things like “I’m awful sorry”, and Jonathan Swift “Your ale is terrible strong” (-ly wasn’t as widespread as it is now). These days, both awfully and terribly mean little more than “very”.

But how do such terrible words enter the extravagant embroidery of our lexicon?

The history of awesome illustrates that it's through a process of semantic weakening. At its core is awe, a powerful word first attested in the 9th century meaning “terror” or “dread”. Often the horror was mixed with veneration because it was regularly used in reference to divine beings. So when the compound awesome “full of awe” arrived on the scene in the 16th century, it also had the meaning “profoundly reverential”.

And as the word spread its wings, so the monstrous sense faded to “overwhelming”, “staggering”, and eventually in the 20th century it took the positive turn we’re familiar with today — awesome now refers to something superlative, or in a thoroughly weakened sense, something simply satisfactory or acceptable. (As an aside, "very" shows the same weakening — its original meaning, “truly, truthfully”, is still preserved in verily and very as an adjective, as in, "my very words").

Violent beginnings

There are several different brands of linguistic extravagance out there. Many draw from force and violence.

Australian English "ripper" (“Bloody ripper, eh?”) presumably has its origins in the 17th-century noun ripper, which meant “person or thing that rips”; it took a particularly nasty turn for the worse in the 1800s before becoming a “person or thing that is particularly good”. And, of course, the so-called “great Australian adjective”, bloody, falls into this same category — associations of bloodshed and murder would have made bloody a very suitable intensifier (and we’ll spare you the adjective tests that show it actually isn’t an adjective).

Other “shock and awe” words have sprouted from expressions referring to quantity or size (super), (un)reality (unreal), and upper or outer position (peak, far-out). Many have unclear histories, though, and Australian English "grouse" falls into that category (though the Australian National Dictionary suggests the British-dialect word "crouse", meaning “bold, cheerful”). Some have gone down quite different paths with complicated twists along the way.

Once-popular "groovy" originally meant (not surprisingly) “having a tendency to run in grooves”. It applied initially to railways before it moved onto jazz musicians (those playing easily; i.e. in the groove) — and from this use it turned into a general term of approval.

Short and saucy

Extreme words are short-lived — in the case of something such as "awesome sauce", spectacularly short-lived.

While it might not seem “groovy”, “radical” or “grouse”, when these words no longer grab our attention, they have to be renewed. This promotes a kind of ever-grinding lexical mill churning out new and clever, eye- and ear-catching expressions that will themselves become the living dead and have to be replaced.

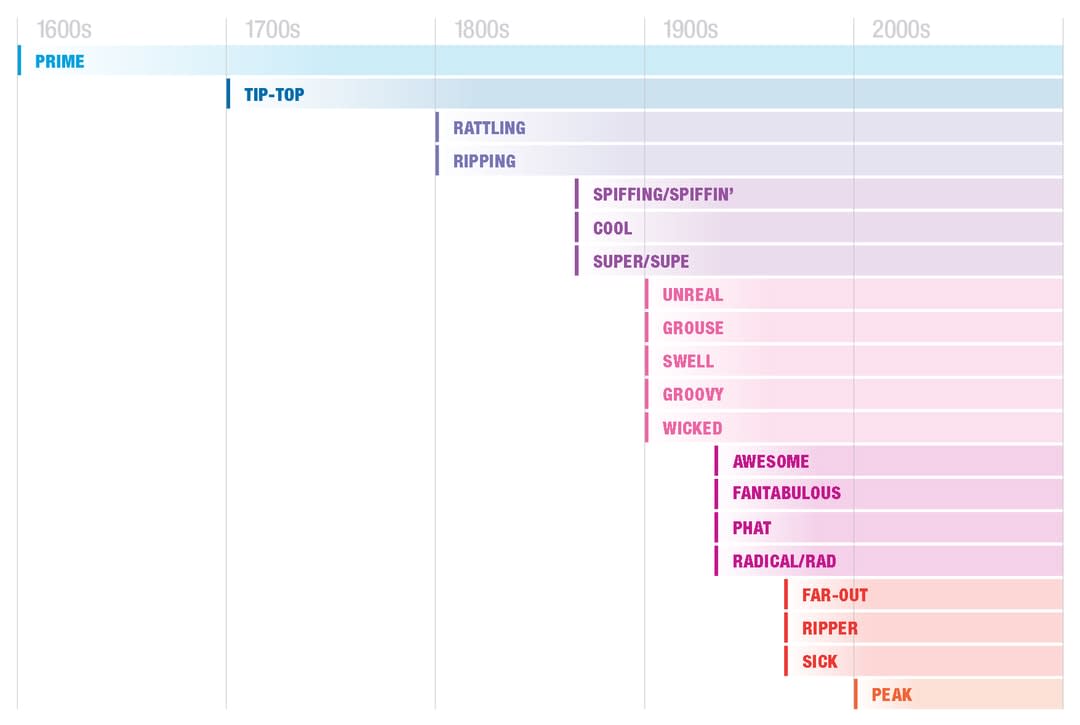

Over the past few centuries, literally hundreds of these have been created (and that’s “literally” in the factual, not exaggerated sense), many of them the “shock and awe” words we’ve just discussed. The graphic below captures a handful. The dates here are approximate, because pinpointing the onset of meanings can be tricky, all the more so if they're part of the slang of an in-group.

Clearly, what’s also driving a nail into the coffin of these expressions is that they typically start life with their feet firmly planted in slanguage — and trendy words will always stop being trendy.

Only the “super cool” will survive

Now, in the interests of providing awesome content here, we'll point out one final interesting aspect to the life cycle of these words. The words in the above list are all well and truly passé, with the notable exception, that is, of cool and super. These two lexical superstars have not only survived over the centuries, they've somehow managed to retain their original energy as well.

The longevity of these words in our colloquial language is an anomaly. Somehow they've captured our imagination and so have survived. But puzzling is still how they manage to maintain their vigour over so many years.

Youth do the heavy lifting when it comes to breathing life into our linguistic embroidery. And while they’ve clearly not lost their love for “cool” and “super”, rest assured they’re busily coining some “mightily” and “wickedly” good innovations.