Technology and the truth: Novel approaches to combating misinformation

Since the advent of web-based social media platforms, the creation and dissemination of information is no longer in the hands of a few.

Citizens can now simultaneously be creators, consumers and spreaders of content. The analytics and algorithms of social media mean citizens have a new power not only to create information, but also to disseminate information by posting or reposting, and this has led to a large increase in the volume of information circulated.

Much of this information is authentic, but it’s also opened the door to “questionable content” such as fake news, hate speech, misinformation, disinformation, and other problematic material that might be locally created or represent foreign interference.

When it’s reposted by “super spreaders” such as entertainment or sport celebrities or politicians, it’s perceived to have their endorsement and is more likely to be accepted and reposted by their large number of online followers.

Often, but not always, questionable content is politically or ideologically motivated. It has the potential to cause collective victimisation by changing popular opinions and attitudes, creating scepticism towards government and the electoral process, causing political unrest and communal violence, marginalising certain communities, and damaging the economy.

Dealing with problematic content

There are growing calls for greater government regulation and for social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, to take down problematic content.

The big question that governments around the world are grappling with is how to regulate information systems, and specifically questionable content.

Government-imposed regulations can eliminate or restrict the flow of questionable content, but at the same time can act as a legally sanctioned mechanism to gag real news and, ultimately, violate media independence, freedom of information and expression.

Read more: Ain't That The Truth: What Happens Next? podcast on fake news, part one

Claiming that it’s necessary to stop rumours from spreading and to prevent violence between communities, we’ve seen several governments impose a localised shutdown of the internet. They argue the national security imperative, but it also conveniently prevents people in that jurisdiction and beyond from knowing what’s happening, including the other measures and behaviours the security agencies might be relying on.

Getting the balance right might not be possible. Legislation and regulations, by their very nature, are unlikely to be a satisfactory solution to the problem of questionable content, especially as it’s often difficult to find the originator.

And when it comes to blocking or deleting content, are we to empower public servants to be the verifiers of truth and the arbiters of what’s acceptable?

Can the platforms be trusted to do the right thing?

In response to community concerns, platforms such as Facebook are starting to accept they have a responsibility for the content they host.

With millions of posts every day, it’s not feasible for their employees to identify and take down questionable content. Instead they rely on artificial intelligence technology to automatically identify and delete harmful images.

But can we trust the super-wealthy owners of the platforms to design the analytics of their AI technology without political or cultural bias? If they’re made responsible for content on their platforms, then they – unelected and unaccountable – are also empowered to determine what is inappropriate content and what constitutes a violation of community standards.

A range of approaches is required to limit the production and dissemination of questionable content, and officialdom needs to change the way it communicates in the digital age.

But which community’s standards are to be respected?

Recently, photos taken in Vanuatu of a traditional ceremony were deleted by Facebook for violating its nudity standards. The Pacific island community was outraged that Facebook had decided that images of their cultural ceremony involving women wearing grass skirts was considered unacceptable. Eventually, Facebook relented and restored the images.

Legislation and regulation to extend the standards and penalties that apply to traditional media to information on web-based platforms seems reasonable.

But as this in itself is unlikely to stop the creation and dissemination of questionable content, there needs also to be a focus on hardening the target by making citizens more cybersecurity-aware to protect themselves from the content and from spreading the content. Cybersecurity awareness programs can improve the public’s ability to discriminate between real news and questionable content.

In addition to these measures, other innovative measures have been introduced with some success.

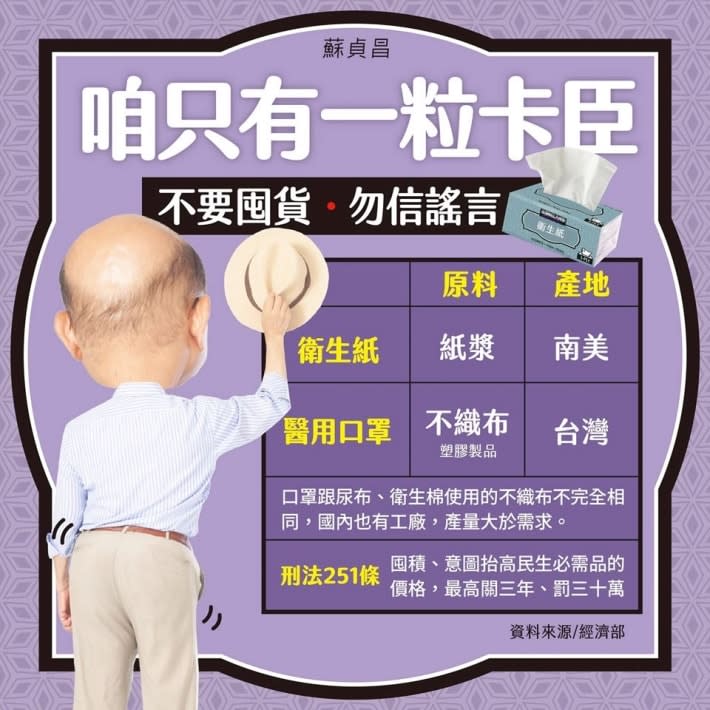

Taiwan has adopted a “humour-over-rumour” strategy to counter misinformation. For example, to counter rumours of a shortage of toilet paper during the COVID-19 pandemic, a meme of the Premier showing his rear was captioned “We only have one butt” to make people feel silly about panic-buying toilet paper.

In another meme, Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare used a “spokes-dog”, a Shiba Inu, in the place of a spokesperson to communicate the government’s messages. The cute image draws people in and moves them to share it through their social media groups with family and friends.

In the example below, the spokes-dog advises the public to wash their hands with soap before eating, after visiting a hospital or the toilet, and after sneezing, to protect themselves and others.

In another image, the spokes-dog cautions the public not to make jokes about COVID-19, even on April Fools’ Day, as these can misinform people. The spokes-dog advises that if someone makes or spreads fake news and misinformation that might cause damage to society, they’ll be liable for a fine of up to NT$3 million (about A$150,000).

Using humorous, widely appealing images, the Taiwanese government has been effective in gaining the public’s attention, communicating public messages, and effectively countering and reducing the dissemination of questionable content.

Rather than seeking to control or regulate the technology, Taiwan’s humour-over-rumour approach uses it in a manner sympathetic to the motivations of those attracted to the medium. Like the best advertising campaigns, it reaches and resonates with the target audience.

Ultimately, a range of approaches is required to limit the production and dissemination of questionable content, and officialdom needs to change the way it communicates in the digital age.

Posting a crested media release or exhorting the public to visit a government website fails to tap into the emotions and behaviours of social media users, and is unlikely to be effective.

This article was co-authored by Nicholas Coppel, an independent researcher, and former career diplomat and Australian ambassador to Myanmar.