In February 2006, Tourism Australia launched an international tourism campaign with a television advertisement showing images of everyday Australians set against a backdrop of famous landmarks, concluding with the ockerish Australian invitation: So where the bloody hell are you?

The ad was censored in North America and banned from British TV. The then Minister for Tourism, Fran Bailey, responded:

“This is a great Australian adjective. It’s plain speaking and friendly. It is our vernacular’.

And she persuaded the British to broadcast the ad.

Bloody may look like an adjective, but it’s not

Back in 1847 Alexander Marjoribanks published in London his Travels in New South Wales, wherein he wrote:

“The word bloody is a favourite oath in that country [New South Wales]. One man will tell you that he married a bloody young wife, another, a bloody old one, and a bushranger will call out, ‘Stop, or I’ll blow your bloody brains out’.”

Marjoribanks speculated that a bullock-driver would use bloody 18,200,000 times before he died!

Back in Sydney, NSW, euphemism was preferred:

The London Commission on Labour says of the Great Australian Adjective:

“It is in general colloquial use among the lowest classes, and is frequently used as a qualifying adjective, but its derivation attaches no sanguinary meaning to it.” The said derivation being from the Anglo-Saxon “blodig,” which means “very.” (The Bulletin, April 28 1894 p.15)

There are a couple of things wrong with this. Old English blodig is sanguinary; it means “bloodlike”, as in ‘Þý ilcan geare wæs gesewene blodig wolcen on oftsiðas on fyres gelicnesse’ (“In the same year a bloody cloud in the likeness of fire was seen again and again” Annal 979, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle).

The slang word bloody might look like an adjective, but it doesn’t function like true adjectives. Adjectives like red or sharp allow for attributive uses such as this red book, this sharp knife, which mean more or less the same as the predicative uses this book is red, this knife is sharp.

But this knife is bloody is not a paraphrase for this bloody knife unless both have the literal sanguinary meaning; the slang sense is excluded.

Coupled with nouns, adjectives, participles and verbs, bloody emphasises the speaker’s emotive attitude to the state of affairs he or she is talking about; in other words it is an intensifier:

- This bloody bloody/blunt knife

- You’ve bloody broken it

- He’s bloody pissing me off

- It’s only a bloody copy!

Or Senator Jacqui Lambie’s impassioned:

“It is not a choice for many of us to be on welfare. It is shameful and it is embarrassing, and it is bloody tough. For you to take more money off those people, you have no idea how bloody tough it is’ (March 23 2017).

The fall from grace

There are two origins for bloody. The sanguinary one is that the colourful associations of literal bloody battle and bloody murder made bloody a very vivid intensifying word. Awfully and horribly have similar violent origins.

A second source involved the so-called bloods, the young aristocratic louts of the 17th and early 18th centuries when descriptions like drunk as a blood meant that an expression like bloody behaviour would have had double significance: objectionable behaviour, something you might expect of a young tearaway, with the added force of the intensifier bloody.

In 1711 the Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral Dublin, in letters to Esther Johnson, described the weather as ‘bloody hot’ (Letter 22, April 28, 1711, Letter 24, May 24 1711), later it was ‘bloody cold’ (Letter 31, September 25 1711).

In 1716 Alexander Pope, in A full and true account of a horrid and barbarous revenge by poison: on the body of Mr. Edmund Curll, bookseller, reported Mr Curll telling his wife he was ‘Bloody sick’.

In the early 18th century, the intensifier was obviously no more impolite than frightfully.

By 1847 Marjoribanks was referring to bloody as an ‘oath’ and The Bulletin of 1894 implies it had fallen into disrepute.

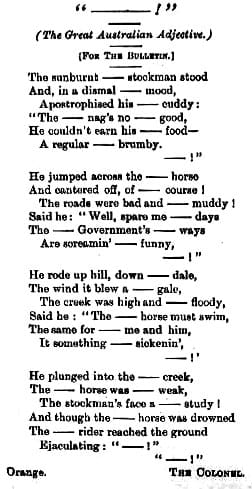

By 1914, bloody had become such ‘a horrid word’ that Eliza Doolittle’s scandalous outburst in Act III of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, ‘Walk! Not bloody likely’ became ‘the Unprintable Swearword’, ‘the Word’, ‘Shaw’s Bold Bad Word’, which, if represented at all, was a dash or set of asterisks. It was unprintable in The Bulletin (Sydney NSW) 11 December, 1897 p.11:

Why this fall from grace? In part a bogus etymology that derived bloody from By our lady calling on the Virgin Mary, and/or from God’s blood (the blood of Christ).

These two blasphemous and profane expressions are expletives (as is F–ck! Bloody hell!) but bloody itself is not an expletive, it’s an epithet. Second, bloody’s lurid associations meant it was much used by the criminal classes, according to Captain Grose in his Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1795).

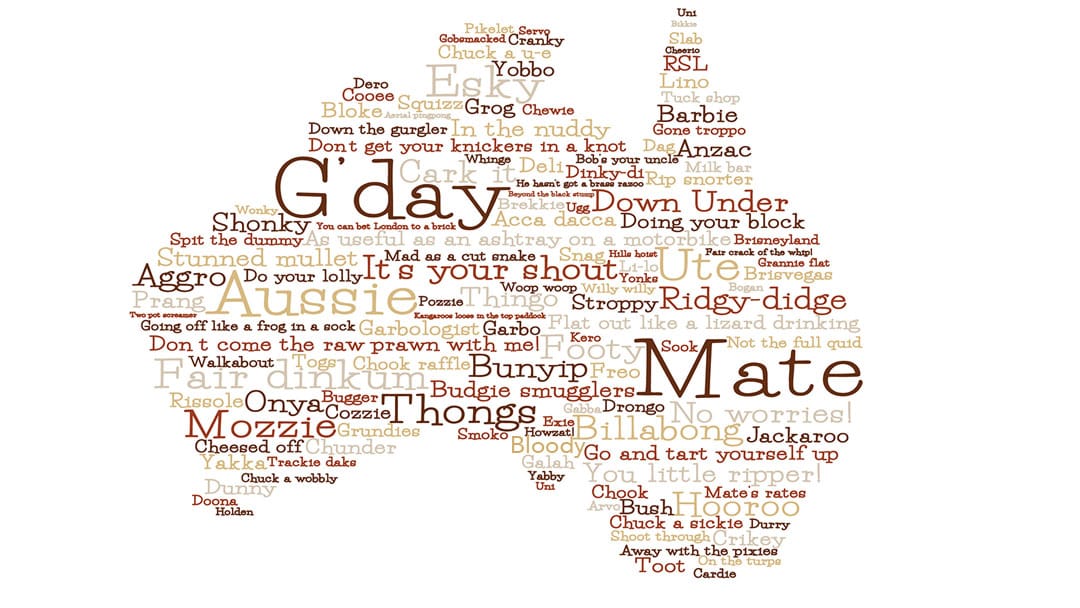

This connection with the underworld explains its currency in the colonial slang of Australia, many expressions from which are still used today (and not all are disreputable): beak (magistrate), chiv, dollop, floor (someone), lag, mug (face), nose/snout/grass, patter, pig (police), pinch, seedy, snooze, stash, sticks (furniture), swag, topped, weed (tobacco rather than marijuana), yarn (see James Hardy Vaux’s 1819 Dictionary of Criminal Slang and Other Impolite Terms as Used by the Convicts of the British Colonies of Australia).

And today?

In our recent survey on classic Australian slang terms bloody featured in 2.28 per cent of the 4523 responses. Elsewhere, we found that it occurs in about 0.2 per cent of sentences Aussies use.

So yes, it’s used a lot. However, a similar collection of conversations in the UK revealed that bloody occurs in nearly 0.3 per cent of sentences Londoners use, which surely cannot be accounted for by the popularity of ‘Neighbours’, nor the lure of Lara Bingle.

Go to our website to catch up on other discoveries on the history and evolution of Aussie slang, and to comment on this article. We’d love your feedback.