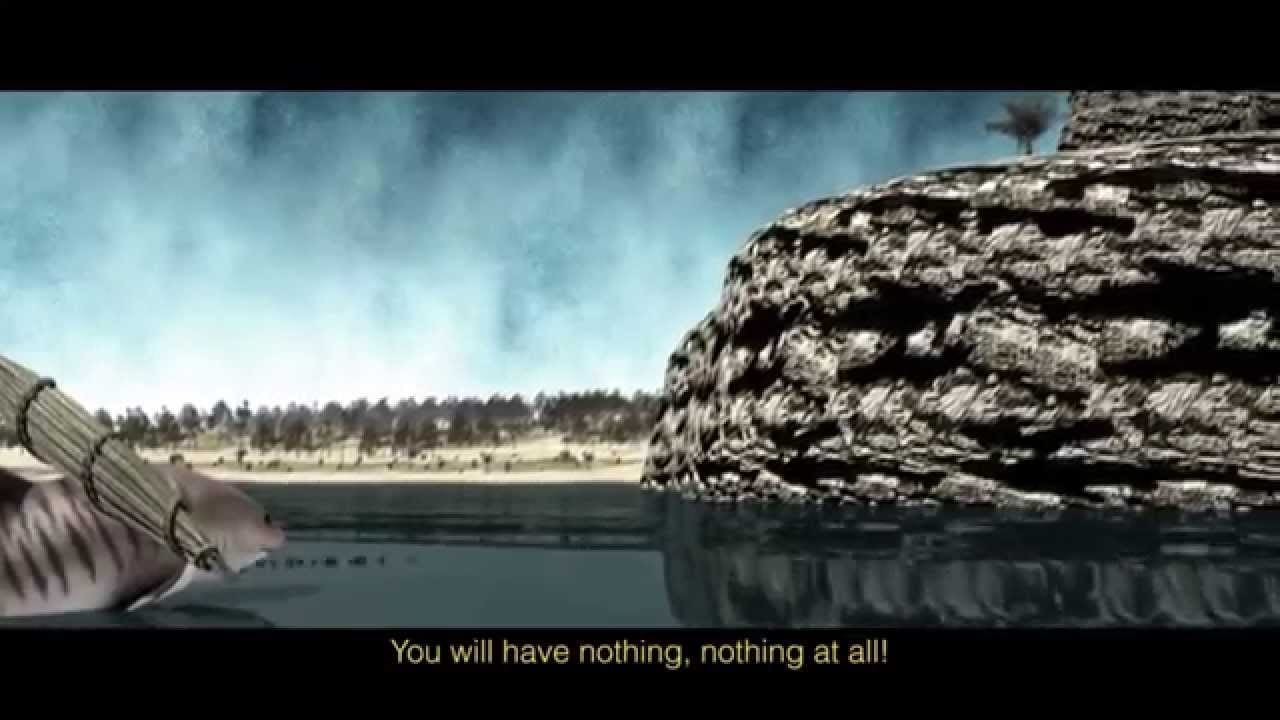

Once upon a time, the tears of the Moon had the power to bring the dead back to life. The story of how the Moon lost its power, and why it waxes and wanes, is a traditional story told by the Taungurung people of central Victoria. After waning for more than 100 years, the Taungurung language itself is also being brought back to life.

Winjara Wiganhanyan (Why we all die), the Taungurung people's story of the Moon, is one of the 3D animations produced at Monash University by Wunungu Awara: Animating Indigenous Knowledges, formerly known as the Monash Country Lines Archive (MCLA). Since 2011, the program has been animating and recording Indigenous stories and songs in their own language. The animations serve at multiple levels – they can be viewed as entertainment, as educational tools, and as ways of stimulating greater community interest in Indigenous languages and cultures. The animations also provide a 3D view of how the country looked before Europeans arrived.

In the case of the Taungurung, the animations are possible because of the painstaking work done by community members to expand the list of Taungurung words. This was done by examining 19th-century records – diaries, letters and reports – for traces of Taungurung.

In 2011, the Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages published a 400-page dictionary of Taungurung words, complete with a pronunciation guide, established through long consultation with community members, and the advice of linguists. The Dolodanin dat Animation Project group, a group of Taungurung people, then came together to help produce the animations.

Linguist and Monash Associate Professor John Bradley, who founded the Monash Country Lines Archive in 2011, says “the statistics are grim, really grim".

"About 230 years ago there were at least 275 different languages being spoken in Australia, with probably 600 dialects of those languages. Now we are looking at probably 20 languages that are still considered strong. We have lost an enormous amount. Older people are dreadfully worried.”

Read more: The power of ancient Indigenous oral traditions

He says that for Indigenous peoples across Australia where languages haven't been spoken for decades, the animations “become a fire-lighter, if you like, for a complete re-engagement with old people’s knowledge, with language, with landscape, with all the things that we think might not exist down here”.

In other communities, such as the Yanyuwa on the Gulf of Carpentaria, where some elderly speakers still exist, the animations represent “a process of future-proofing", he says. “And I think that’s what the Indigenous people we work with are really aware of. They are trying to future-proof culture, language and knowledge so that something is there for future generations. It’s like leaving a last will and testament.”

Dr Bradley is one of the few people who can speak Yanyuwa.

In the late 1980s, he had the idea that animations might be a good way of preserving Yanyuwa stories, and in the ’90s he began preparing storyboards. But when he showed the Yanyuwa people examples of animation styles, they were dissatisfied with them, and said they would prefer any animation to look like their own country.

As it happened, Dr Tom Chandler at Monash University’s SensiLab was exploring the potential of 3D modelling and virtual world-building as an interdisciplinary tool for re-creating lost landscapes (he's best-known for his work on re-creating 12th-century daily life at the Cambodian temple complex of Angkor Wat). SensiLab animator and visual effects specialist Brent McKee was assigned to work with Dr Bradley on the Yanyuwa animations.

“Maybe Brent was born to it, I don’t know, but from the word go he had an understanding of what was required,” Dr Bradley says.

The Yanyuwa people were enthusiastic about the results and began working with Dr Bradley on preparing stories for animation.

Read more: An outdoor gallery that began in the Ice Age

In 2011, former Monash chancellor Alan Finkel, now Australia’s chief scientist, saw an early animation and offered to financially support the then-Monash Country Lives Archive through a charitable trust, the Alan and Elizabeth Finkel Foundation. This support has helped the project complete seventeen animations, with a further seven in production or awaiting community approval. Communities are now approaching the MCLA with their own funding for further projects.

“The animations have impact in the community because it's their knowledge,” says Dr Bradley. “You just see them come home.”

“Kids are drawn to them, old people are drawn to them, middle-aged people are drawn to them. And what you watch is a whole series of conversations taking place between generations that might normally not have much to do with each other around this kind of knowledge.”

Dr Shannon Faulkhead works full-time for Wunungu Awara, as a research fellow and community liaison. The communities own the copyright for their animations, which are only posted on the Wunungu Awara website when they give permission.

Videos: Watch the Wunungu Awara animations

The communities “need to work through” a number of issues before the animation can begin, Dr Faulkhead says.

What stories do they wish to animate, for instance, and in what style? Some groups want 3D realism, but others wish to use their own artwork.

“Also, which language? Some groups might have a number of dialects, or clan groups, so they need to decide not only which language, but which version of the story they want to tell,” she says.

The communities write the script and provide the voices for the soundtrack. In some cases, the people whose voices are recorded are speaking their own language for the first time.

“For the people who have been involved, it's been an extremely powerful process, quite transformative,” Dr Faulkhead says.

What effect the animations will have on the wider revival of language in individual communities isn't yet known.

“It’s one of the things we would really like to have a look at,” she says. “There’s a saying – an old person dying is like a library burning. All that knowledge and information goes with them if they haven’t been able to pass it down to the next generation.

"Now I’m noticing that it’s not just the old people who are pushing this. It’s coming from both ways now – the younger ones are saying we want to learn, we need to learn. This is one way of doing that.”