“Someone once called me Barbie in class. They’re like, ‘You look like a Barbie studying maths’, and I was like, ‘What?’. […] That always stuck with me that I didn’t want to look like this stupid bimbo in the class. And so sometimes I’ll be like, ‘Don’t talk’. Even if I’m burning to ask a question, I’m like, ‘I’ll look like an idiot. I don’t know how to do this, but I’ll look like an idiot.’” – Eloise*, third year, University Y)

The above quotation comes from a participant in our research about the supports and challenges experienced by first-year and third-year undergraduate mathematics students (majors or minors) at two prestigious Australian universities.

Participants took part in individual and focus group interviews, in which they shared photographs that represented their experiences. The sexist comment made by the participant’s peer is disturbing because it led to her being afraid to ask questions, for fear of looking stupid. As such, she presumably developed less understanding of the mathematical content, since her misunderstandings were not addressed.

The men and the first-year women in the study rarely shared personal stories of differential treatment by gender, but such stories were common from the third-year women, many of whom commented that they feel pressure to succeed, as “representatives” of their gender.

For instance, Irina (third year, University X) noted: “Failing at a concept often feels like failing as a girl. Or, as a female in mathematics, I feel very representative of that.”

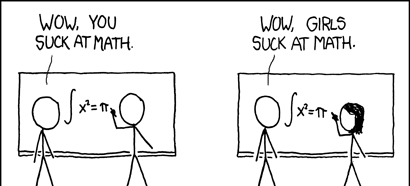

As a minority in university mathematics, particularly at higher levels of study, women are treated as representatives of their gender. Hence, errors are depicted as being due to gender-related mathematical incompetence, rather than any personal misunderstandings.

Gender imbalance apparent in third year

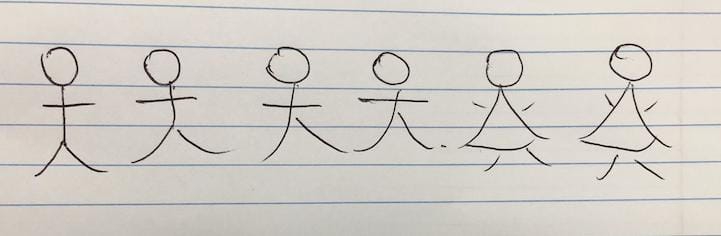

Although mathematics classes are fairly gender-balanced in first year, as students from many programs (for example, science, business) are required to take these introductory classes, an imbalance is readily apparent by third year. Some participants suggested that the gender ratio (men to women) was as high as 9:1 in some third-year classes. Eloise (third year, University Y) shared the following image of her perception of the gender ratio to represent a challenge that she faces during her studies:

Some of the third-year women had even counted the numbers of women and men in their classes. Interestingly, the few participants who were unaware of the gender ratio in their classes were men, which speaks to their privilege as the dominant gender group in mathematics.

The declining proportion of women students as they progressed in their courses was common at both universities, but proportions of women faculty members differed widely between the two institutions. At University Y, concerted efforts have been made in the past few years to increase the number of women faculty members, in contrast to University X.

Consequently, most students at University Y had been taught by at least one woman lecturer, while most at University X had not. A wealth of research shows the importance of role-modelling, especially in fields of study where students are gender minorities.

Concerningly reminiscent of a scene in the movie Hidden Figures (about black women “computers” who worked for NASA in the 1960s), third-year women participants at University Y shared that they would often go across campus to use the bathrooms in another building. Apart from the frequently long queues to use it, the women’s bathroom in the mathematics building was smelly and unsanitary, as shown in the image (right) from Daria (third year, University Y).

The men from University Y did not report any issues with the cleanliness of their bathroom facilities, or with queues to use them. It’s shocking that the women at University Y don’t have proper bathroom access in the mathematics building. Such a situation can make women feel like they don’t belong in the mathematics environment.

In addition to this egregious example, many third-year women (at both universities) shared stories of being underestimated and presumed to be less intelligent than the men in their class – not only by peers, but also by instructors.

Multiple third-year women shared stories of men (classmates) taking markers out of their hands while they were working on mathematics problems on the board, and explaining their own work to them. Beatrice (third year, University X) reported an incident of a tutor assisting a woman rather than a man, even though both were having difficulties: “Two of my friends, one girl, one boy, working at the board, and a tutor going up to the girl to ask if she needed help, when both of them were struggling at the board in the same physical location.” Such an action is indicative of a presumption of women needing assistance in mathematics.

Unwelcoming environment for women

All the micro-aggressions shared by the third-year women are evidence of an environment that’s still unwelcoming to women. Although some of the stories shared may seem like minor incidents, they accumulate over time. How many micro-aggressions must women face in mathematics departments before they decide to leave the field?

This accumulation is reflected in the participants’ career plans – many of the men planned to continue in mathematics to the graduate level (and to academia), whereas only a few women had such plans. Most planned to transition into related fields, such as forensics.

When the women stated an intention to continue with mathematics, they tended to use indefinite language and/or offer backup plans. For instance, Daria was unsure whether to pursue graduate studies or employment, and explained that she has “had job offers, just like, ‘We need data scientists’, and I’m, like, ‘I’m not that good’.”

Several researchers have shown that boys and men are overconfident in their mathematical abilities, with such feelings reinforced by years in societies and educational systems where this ability is assumed based on their gender.

In contrast, girls and women are in a constant battle against stereotypes about their mathematical abilities, as in the “Maths Barbie” example shared at the start of the article. Hence, we may lose girls and women from the field who are just as talented as boys and men, but who lack confidence in their abilities.

Talent we can't afford to lose

It’s not enough to simply assume that if women begin university studies in mathematics, then everything will be OK. As our research shows, women continue to experience a “chilly climate” in university mathematics, which is linked to their lack of desire to continue in the field.

We can’t afford to keep losing mathematical talent. If the same types of people continue to succeed and progress in mathematics, then it will remain a field that has a certain type of culture, which has been repeatedly shown to be inhospitable to women.

Multiple third-year women shared stories of men (classmates) taking markers out of their hands while they were working on mathematics problems on the board, and explaining their own work to them.

When this kind of culture is replicated across universities, ultimately, Australia suffers – economically, in terms of wasted talent, and socially, in terms of stereotypes and prejudices that hold women back.

However, there are some steps that can be taken to arrest this brain drain from mathematics. In order to effect change at a systemic level, we strongly recommend that faculty members in mathematics departments undergo professional development on the topic of gender issues in mathematics so that they can enhance their skills in addressing sexism and gendered micro-aggressions in their classes, as well as examine their own behaviours. Students of all genders need to act as allies to their women classmates, calling out sexist behaviours when they occur, and ensuring that women have a safe space to explore mathematics.

Culture and the system are the problem

Importantly, our recommendations pertain to the culture of the mathematics departments, not to the women themselves. They are not the problem – the system and culture are.

As argued by UK researcher Heather Mendick, the reason that interventions to address gender issues in mathematics are rarely effective is that “they have attempted to change the girls and women to fit into maths while being happy to leave maths fixed as it is”.

With our research, we’re hoping to change the culture of mathematics so it becomes an inviting realm for people of all genders.

* All names have been changed.

The research reported in this article was conducted by a research team comprising Dr Jennifer Hall, Professor Jane Wilkinson, and Mr Travis Robinson at Monash University, and Dr Jennifer Flegg at the University of Melbourne.