Science still can’t explain what in us groans at the alarm clock, why we’re gladdened by a carolling magpie, or like the smell of coffee.

This riddle – what is consciousness? – is sometimes called the “hard question”, because despite advances in brain mapping and neuroscience, the nature of consciousness remains a mystery.

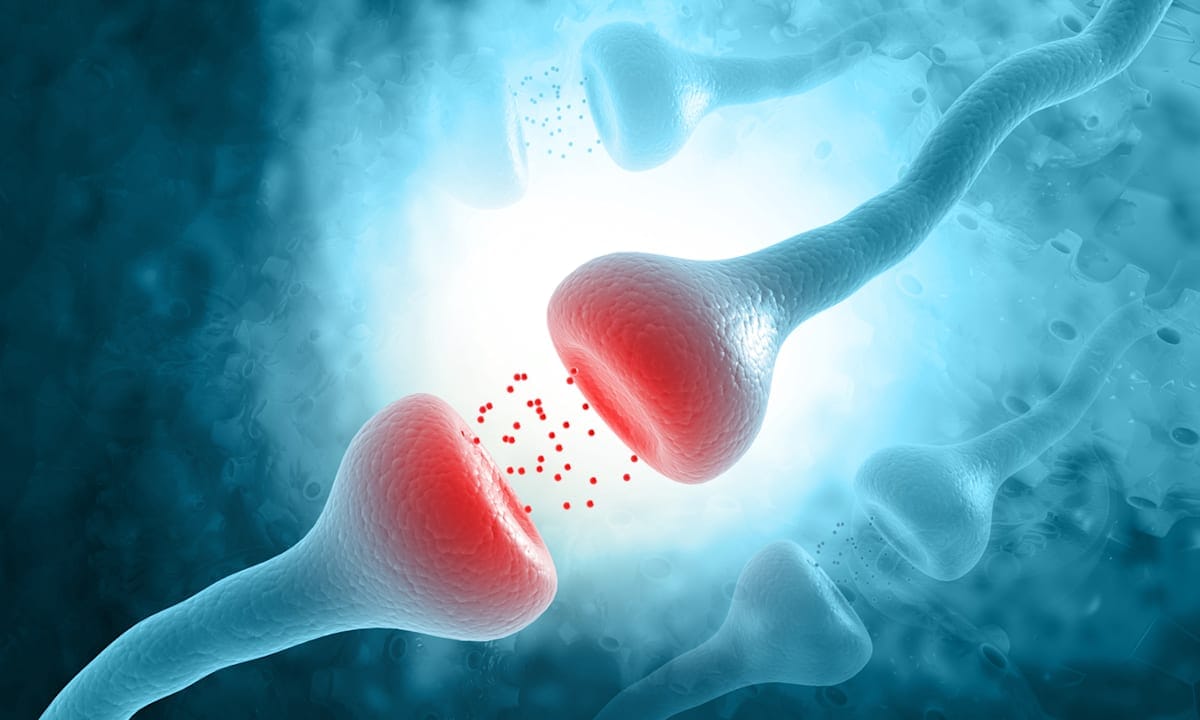

“We don’t know how firings of neurons in the brain give rise to our subjective experience of the world,” says philosopher Jakob Hohwy.

“We can imagine a computer that’s wired up just like a brain. We can also easily imagine that computer is not conscious. It’s just the firing of neurons. It’s very hard to make the bridge from firings of neurons, electrical discharges between the cells, and then, what makes you, you.”

Professor Hohwy studies the science and philosophy of consciousness in his Cognition and Philosophy Lab. He’ll also head Monash University’s new Centre for Consciousness and Contemplative Studies, which has received $12 million in philanthropic funding from Martin and Loreto Hoskings’ Three Springs Foundation.

The centre, due to open in early 2022, will be led by philosophers and humanities researchers and house neuroscientists, psychologists, and medical doctors.

It will be a leading research centre for consciousness and contemplative studies, teaching contemplative practices to students and the broader community, and will also conduct interfaith dialogue.

A philosophical and physical problem

Contemplative practices are being studied alongside consciousness, because the ways in which they change our physical and emotional states is “both a philosophical problem, and a mind/body problem”, Professor Hohwy says.

Philosophers have long tried to explain what in us gives rise to subjective experience, he says.

“And it’s also now increasingly a scientific question … Neuroscientists and psychologists are trying to explore the brain-basis of consciousness.”

Meditation and contemplative practices are also important in most religious traditions. Meditation is integral to Buddhist practice, for instance, and has also informed Buddhist philosophical ideas about consciousness, says philosopher and Buddhist scholar Monima Chadha.

“In Buddhism, these two things are intimately connected. They’re not studying consciousness and doing meditation, they’re thinking of the study of consciousness as providing the theoretical background for these meditative practices – why they work, and all of that,” she says.

“Meditation is not an investigative method leading to new discoveries about the mind. The Buddhist approach is premised on the idea that meditative practice serves to turn principles like impermanence, no-self, that are proven through scriptural study and rational inquiry into objects of experience.

“In this sense, meditative understanding is continuous with, and dependent upon, preceding philosophical analysis; it has no independent epistemic value of its own,” she says.

“It's very unusual for anyone in consciousness science or research to think that there could be any change in any consciousness state without some change in some brain state.”

Can science alone investigate this paradox?

“It’s a good question, because I think there’s a quite strong feeling that when we do the neuroscience of meditation and consciousness that we’re trying to reduce away,” experiences “that can’t be materialised or reduced,” Professor Hohwy says.

The challenge for the centre is to find ways of researching these mysteries, in a way that honours the complexity of human experience and the scientific method.

Spiritual traditions have long acknowledged the difficulty.

According to the Buddhists, meditation should lead to the attainment of “four immeasurables” – loving kindness, empathy, compassion, and equanimity – Dr Chadha says.

She hopes the centre can “devise ways of thinking about how they might be measured”.

Could meditating for, say, 10 minutes a day, help one become more compassionate, for instance, and can this be assessed in a lab?

Where psychology and science meet

Professor Hohwy envisages engaging psychologists and cognitive scientists to collaborate with this task.

“It's very unusual for anyone in consciousness science or research to think that there could be any change in any consciousness state without some change in some brain state,” he says.

“There’s a materialist foundation for this, but that’s not the same as saying that you can explain every subjective aspect of consciousness by just listing changes in neurons that fire certain ways. That’s where the interesting philosophical work is done. What are the limits to our capacity of explaining subjective experience?”

He says Dr Chadha’s background in Buddhism has been useful in placing mindfulness practices in a historic and philosophical context, rather than simply seeing it as “a product, an app on the phone”.

“The ethical side, the interpersonal side of this, is really important and exciting, as far as I'm concerned,” Dr Chadha says.

The centre will also look at “other faith traditions and secular and humanist traditions, to see what the contemplative practices look like there”, he says.